This is the second in a series of three summer essays. The first piece introduced neomedievalism, an analytical concept recently advanced in medieval studies; this one explores neomedievalism’s broader relevance to how historians and nonhistorians talk about history in the public sphere; the last will make some suggestions as to how all this might influence how historians approach writing history.

The [conspiracy theorist] is all idée fixe, and whatever he comes across confirms his [theory]. You can tell him by the liberties he takes with common sense, by his flashes of inspiration, and by the fact that, sooner or later, he brings up the Templars.

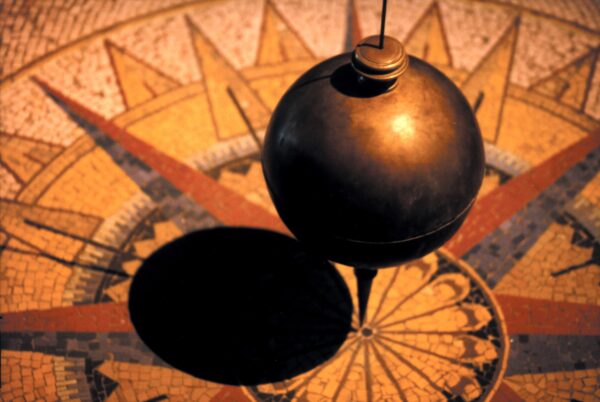

(Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum)

When people come to historians with narratives we know to be false, it’s hard to take them seriously. I remember, with some consternation, my first encounter with an adherent of the phantom time hypothesis (PTH). For the blessedly unfamiliar, the PTH postulates that Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, Pope Sylvester II, and perhaps Roman Emperor Constantine VII conspired in 911 CE to invent the previous 297 years of history in order to solidify Otto’s rule. This theory was first proposed in 1991, and its adherents claim that everything from legal documents to letters and chronicle references documenting this period are all forged. And so they believe that we are living in the year 1724, not 2022.

Like every good lie, the PTH has a small nugget of truth. Contemporary documents for the period between 700 and 1000 were often copied in the second millennium as their originals faded, wore out, or just because their owner wanted to have another copy. In many cases, due to wars, pests, carelessness, and deliberate destruction, only those later copies now survive. This fact is central to a substantial academic historiography, since it is unclear if we can trust these later copies to accurately describe the original period. Some of them may have indeed been forged.

The PTH is also a product of some very long-lived ghosts which continue to haunt medieval studies. It is based, for example, in a myopic, nationalist eurocentrism that has long defined the field, one which forgets (or does not believe) that there is any premodern history outside of Europe. To find definitive proof that PTH is wrong, to show that it is the year 2022, one must merely remember that the Mayan, Islamic, Ghanian, and Chinese empires existed and produced documents, artifacts, and other historical sources. Even if every surviving European document dated to between 700 and 1000 was a forgery, non-European calendars correspond to European Christian reckoning of time. Finds from European archaeological sites, radiocarbon dating, and dendrochronology provide final nails in the coffin.

Like every good lie, the phantom time hypothesis has a small nugget of truth.

But despite all evidence to the contrary, the phantom time hypothesis persists. And like QAnon and other popular delusions, it does no good to argue facts with a true believer. Whatever “facts” they come across confirm their belief. I found only frustration as the reward for countering that PTH adherent’s patent illogic; Umberto Eco’s protagonists in Foucault’s Pendulum paid with their lives for the attempt to diffuse a conspiracy (which they themselves had invented and sold to conspiracy theorists). You can’t use logic to convince someone that their illogical belief is wrong, after all. In fact, as research on vaccine refusal reveals, the mere effort of trying to refute mistruths can do more harm than good by introducing new audiences to the idea.

By making it the locus of power for a constructed conspiracy theory, Umberto Eco used Foucault’s Pendulum in the Panthéon to unite irrational belief with rational science. Bee Ostrowsky/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

That truth, that logic does not actually counteract illogic, is a bit of a blind spot in the modern era’s positivistic, objective, scientific approach to learning and education. More and better speech cannot counter bad speech. You can’t simply educate an unwilling individual into being what you consider to be a better person because there is a fundamental disconnect regarding what “being a better person” actually means. This is not a reality which the current legacy of the Enlightenment is equipped to handle. Indeed, it is a reality antithetical to that legacy.

This unbridgeable gap is the monster in the room for historians talking about race, gender, and sexuality to an audience invested in the selective use of historical fact as confirmation for contemporary identity and explanation for their current anxiety. Those who believe that critical race theory is a Marxist indoctrination campaign for elementary schoolers or that Confederate statues are an unproblematic component of a proud heritage do not believe themselves to be ignorant or in conflict with factual reality. There is therefore no stable ground on which an interlocutor might stand to convince them otherwise. And there is, I think, something about this that is particular to the study and practice of history.

All these conspiracy theories and apparent abuses of history do have a logic and reason behind them, and the justification of this structure is almost universally historical, the product of dirtbag historicism, the idea that myth must still obey historical fact. Eco’s fictional fictional (stet!) secret society, the Templi Resurgentes Equites Synarchici (the Resurgent Synarchic Knights Templar), took their authorization from a historical legacy. PTH adherents argue from historical fact. Great Replacement ideologues, those who believe the “White race” is under demographic threat, base their beliefs in a fictive memory of a White past. Rioters in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 claimed via heraldic apparatus to be perpetuating the legacy of the Holy Roman Empire, the Confederacy, and Nazi Germany as they defended a statue of a historical figure, Robert E. Lee. And so on. Thus, although there is an easy tendency among the educated to fixate on how such ideas are wrong, I think it is much, much more important to emphasize that their believers believe them to be cold, rational, historical fact.

There are no reforms to current academic production or writing that can answer such feigned histories.

Looking at conspiracy theories through the lens of “dirtbag historicism” reveals a dilemma. There are no reforms to current academic production or writing which can answer such feigned histories, no factual rebuttal which offers a counterargument against the fantastic justifications of those invested in an idée fixe. No Ken Burns documentary, museum exhibition, viral Twitter thread, or historian publishing with a popular press will convince. But if historians give up on the conversation, retreat, and cede areas of the public forum to such ideas, they not only let them run unchecked; they concede that how they do history cannot address the most dangerous aspects of the public discourse. Historians’ current tools, methods, and pedagogies cannot prevail in this lose-lose scenario. Instead, we must change the terms of the game.

What, then, are we to do? Eben Horsford, fixated on his Norse foundation of America, knew. To counter a narrative, one had to construct a more believable one—a narrative which people want to believe. Horsford, as we have seen, did this with statues, and it is not a coincidence that similar statues are the subject of so much controversy now. To grapple with how these individuals and groups use history, historians must have the tools provided by fiction at their disposal.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.