Alice Echols’s discovery that her grandfather played a leading role in one of the biggest banking scandals in Colorado’s history didn’t originate in the archive. The revelation began over dinner with her parents while she was researching a separate project nearly 20 years ago. That evening took an unforeseen turn when a teasing remark about the family’s shadowy history caused her mother to burst into tears and flee the dinner table in outrage. Bewildered, Echols persuaded her father to finally break the silence surrounding her mother’s early life.

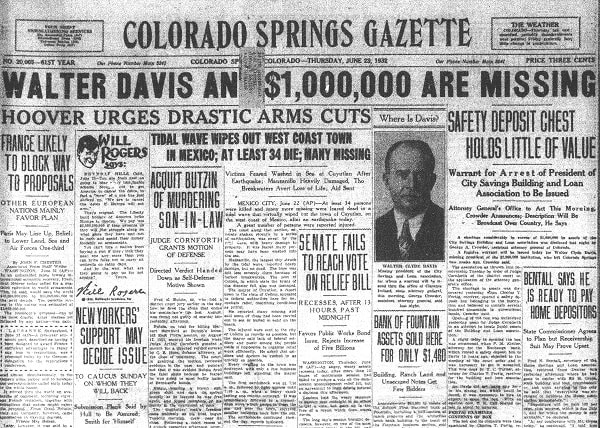

What she learned was that her grandfather, Walter Clyde Davis, whom her mother rarely mentioned, wasn’t a banker who had simply lost his fortune in the Great Depression. Davis was, instead, a notorious criminal whose fraudulent business dealings had brought national disgrace on the family a mere generation before. Once considered a financial wizard, Davis embezzled over $1.25 million—nearly $22 million in today’s terms—from the City Savings Building and Loan in Colorado Springs before the Depression. In her latest book, Shortfall: Family Secrets, Financial Collapse, and a Hidden History of American Banking (2017), Echols reveals Davis’s story and how the sidelined history of building and loan associations altered national perceptions of Wall Street vs. Main Street capitalism, exerting a lasting influence on debates over deregulation in the housing industry. Quietly scrubbed from family memory—like the virtual omission of the B&L scandals in the historical record—Davis’s fraud was far from singular; 60 percent of all B&Ls in Colorado alone were shuttered during the Depression.

Growing up in the suburb of Chevy Chase, Maryland, Echols, now a professor of history at the University of Southern California, was generally aware of a tense silence regarding her mother’s past, as well as the incongruously swanky Art Deco furnishings—evidence of gone-by opulence and prosperity—that distinguished her home from the “midcentury blondness” of the neighborhood. When she was five, she saw her father unpacking a box filled with her late grandmother Lula’s custom-sewn gloves—the fingers of every pair were stuffed with $100 bills. This memory led her, years later, to a survey of the family attic. There, she found Louis Vuitton trunks, packed with memorabilia that had sat untouched over the years.

The documents Echols unearthed—transcripts of subpoenaed telegraphs, diaries, letters, and newspaper clippings—led to a FOIA request for her grandfather’s 200-page FBI file. Ultimately, these documents helped her overturn the vague childhood narrative in which her grandparents were financially victimized by the stock market crash. “All along,” she notes in Shortfall, “an intimate archive of the scandal had been cached inside our house. My mother held on to it all, even though doing so risked the possibility that one of her daughters might discover her family’s secret.”

When she was five, Echols saw her father unpacking a box filled with her late grandmother Lula’s custom-sewn gloves—the fingers of every pair were stuffed with $100 bills.

The book elucidates a once-public tragedy of social climbing, contextualized by rampant state and federal regulatory corruption in the West. A portrait of governmental negligence and the policies that nourished antistate conservatism in the region, Shortfall considers the private and public motives behind investment profiteering. The work reveals the widespread subterfuge that allowed Davis’s actions to be replicated to varying degrees by manipulation of the B&L model across the country through the 1920s. In Colorado, Davis capitalized on opposition to the concept of regulation itself.

The building and loan industry figures as a vital component of our lending and investment landscape. As community-based nonprofits, B&Ls gained national traction after the Civil War. They were frequently operated by amateurs, with depositors meeting in churches, rented halls, and taverns. Prospective home buyers invested in shares, which could be borrowed against to finance mortgages at low interest rates. With real advantages for families of limited means, B&Ls helped launch homeownership as both a practical endeavor and a political ethos.

Yet the nature of the enterprise began to shift in the 1880s, when industrialists and banking executives, seeking to expand to new consumer demographics, started to consolidate, promote, and sell stock in B&Ls nationwide. These executives set up shopfronts that imitated established banking institutions and offered wildly inflated interest rates to lure new, middle-class depositors, frequently crafting agreements that obscured the restrictive circumstances under which clients could retrieve their funds. Revamped B&L associations in large part catalyzed the consumer revolution of the 1920s, and 10 years later, they claimed nearly 50 percent of institutionally held mortgage debt on one- to four-family homes. By 1929, at least 1 in 10 Americans had invested in a B&L. Shortfall reconstructs the complex dimensions of this “legal chicanery aided by beneficent darkness” and unveils the American financial system as it grew ad hoc.

As B&Ls turned millions of ordinary Americans into homeowners, consumers, and investors, Walter Davis emerged as a figure typical of an abusive system. As the owner of City Savings, Davis siphoned extravagantly from investors, but his story proves exceptional in degree rather than in kind. Born into a family his daughter later described as “a bunch of nobodies from nowhere,” the Davis household moved to Colorado from Greensburg, Indiana, in 1905. The cash-strapped family, headed by its tuberculosis-afflicted father, Allen, sent only Walter through high school. Driven by an insatiable desire for upward mobility, as a young stenographer, Walter floated fake reports of his college education and socially prominent marriage to the local papers. He also presented himself as an attorney, shedding his actual vocation as stenography became feminized by the popularization of office machinery in the 1910s.

In a state and a town where the elite felt entitled to run the show, and where East Coast industrialists aided the governor’s office in defeating banking regulation measures, the realm of the legally permissible, Echols writes, was widening for all businessmen, including her grandfather. At the turn of the century, Colorado Springs was a town defined by the excesses of extractive industry. Top-heavy with millionaires and an elite tourist class that listed Theodore Roosevelt on the rolls of the Cheyenne Mountain Country Club, Colorado was also a state where coal-mining deaths occurred at twice the national average. Workers in the shantytowns of Cripple Creek and Colorado City referred to the Springs as Little London, where residents of Millionaire’s Row strolled streets paved, literally, with low-grade gold extracted from the Creek District’s mines. Shortfall documents a culture “loath to erect or enact anything that might act as a roadblock to ingenuity and enterprise,” encouraging ambitious men with unchecked entrepreneurial drive like Davis.

Through shrewd marketing to middle-class homeowners and promises of inflated interest rates, Davis began his ascent to social prominence.

Just seven years after his arrival in Colorado Springs, Davis began operating formally as a moneylender, and in 1914, he acquired City Savings, which was struggling to stay afloat. Through shrewd marketing to middle-class homeowners, and with promises—and, initially, actual payment—of inflated interest rates, Davis began his ascent to social prominence. He also started to take more audacious risks. By 1930, he had spent over $150,000 on European travel and $82,000 on luxury cars, and had purchased more than a half-million dollars of life insurance coverage.

As his spending grew more lavish, he used City Savings as a private honeypot, grafting money into his own accounts for the fictional sale of properties owned by his holding company. Dubbed “Captain Nothing” by a vitriolic press once the extent of his high-rolling theft became evident, Davis embodied the paradoxes of a society riven by socioeconomic extremes. As the Depression deepened and depositors came calling for funds that were no longer on hand, Davis took the path shared by many exposed financiers, resigning from his B&L before going on the lam, and later committing suicide before he could be taken to trial (which would have resulted in the financial and social ruin of his wife and daughter). Along with City Savings, thousands of B&Ls imploded during the Depression, but the New Deal (and its federal deposit insurance policy) allowed these institutions to rebrand themselves as savings and loans. These too would later fail spectacularly, during the Reagan administration.

Reflecting on the project of braiding together micro and macro narratives, Echols notes that while some people may think of family history as “disposable” and not “serious,” she is certain that her mother’s class anxiety and her own memories of it shaped the work definitively. To her dying day, her mother, despite inheriting an estate worth nearly $1 million, considered herself a “nobody.” The long shadow of Walter C. Davis also falls across the legal landscape that abetted his crimes: “my grandfather,” Echols writes, “had a cruel disregard for his customers, whether they were looking for security, a lifeline, or fast money. I wish he had been an outlier, a lone maverick, but he wasn’t.” Reviving an all-but-forgotten history, Shortfall enriches our understanding of deregulation and anti-state conservatism, in all its personal and public discontents.

Jill Wharton is a Mellon Visiting Fellow at the AHA.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.