The annual faculty salary studies released earlier this year by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and the College and University Personnel Association (CUPA) make clear the impact the nation’s current economic problems are having on college and university campuses. The former reports the first decrease in a decade in the overall average salary level of faculty, when adjusted for inflation. While CUPA finds the situation overall more favorable, its data on history faculty salaries is very troubling, indicating even slower growth than in previous years.

Based on a survey of 2,215 institutions, the AAUP study reports that the average salary level for all faculty increased by 5.4 percent in 1990–91 compared to 6.1 percent in 1989–90. But rising inflation essentially wiped out all the 1990–91 gains—when adjusted for inflation, the overall average salary level decreased by .6 percent. the first decline in real salary levels since 1980–81, when the downward spiral of the 1970s ended. The .6 percent decrease leaves the average real faculty salary level in 1990–91 about 8 percent lower than in 1971–72.

One possible explanation for the 1990–91 decline is the retirement of high-paid senior faculty and the hiring of lower-paid junior faculty to take their places—that would result in a lower overall average salary level but not necessarily a real decline in the average salary level for continuing faculty. The AAUP study provides salary data on the latter, and the news is not much better. While the average real salary level of continuing faculty rose by .6 percent in 1990–91, that is the smallest such annual real increase in the past decade and considerably lower than the 2.4 percent increase posted last year. Clearly the nation’s economic recession is having substantial impact, and the situation is not likely to improve over the short run, given that almost 70 percent of full-time faculty are employed at public institutions subject to state budgetary cutbacks. But AAUP suggests that faculty shortages predicted for later in the decade may lead to some improvement, with the most substantial salary increases in the humanities.

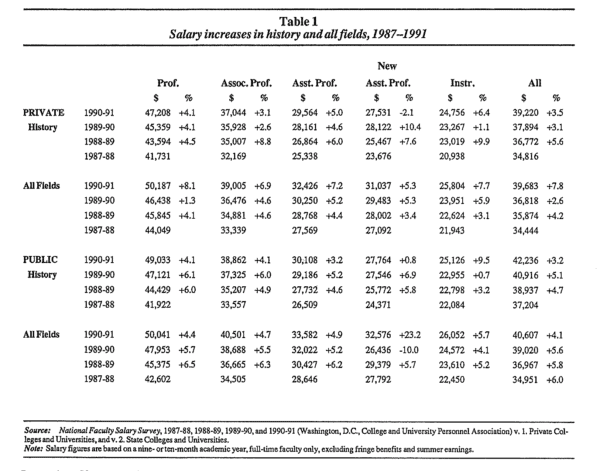

AAUP includes nearly three times more institutions in its survey than does CUPA, but the latter provides the only discipline-specific data, making it possible to compare faculty salaries in history with those in related disciplines and those in higher education overall. According to CUPA’s surveys of private and public colleges and universities, faculty salaries increased overall by an average of 6.0 percent in 1990–91 (not adjusted for inflation), up from that reported in the previous two years. History salaries also rose in 1990–91, but, in contrast, the gains were of diminishing size. For the third straight year, history faculty salaries increased by a smaller percentage than in the previous year—3.4 percent in 1990–91 compared to 4.1 percent in 1989–90, 5.2 percent in 1988–89, and 6.2 percent in 1987–88. The impact of these diminishing gains is most evident in private institutions, where the average salary for history faculty fell below that of all faculty for the first time since CUPA began its survey in 1982. While history salaries at public colleges and universities remain 4.0 percent above that for faculty overall (compared to 4.9 percent in 1989–90), history salaries at private institutions are now 1.2 percent below the overall average (compared to 3.1 percent above in 1989–90). But while historians appear to be losing ground at private colleges and universities, faculty salaries overall grew more there (8 percent) than at public institutions (4 percent).

As in past years, history salaries compare even less favorably by rank-at each rank salaries for historians average less than that for all fields. The overall figure for history is pulled up by the concentration of history faculty at the higher ranks—few other disciplines have a larger proportion of tenured faculty. But at private institutions, that was not sufficient to offset the striking setback in salaries for new faculty. After four years of higher than average growth, the average salary for new assistant history professors in private institutions decreased by 2.1 per cent in 1990-91. New assistant history professors at public institutions fared only a little better, registering a meager .8 percent increase, the lowest for any rank in the discipline. Clearly there is no evidence of higher starting salaries in response to increased demand—the long-awaited opening up of the job market remains in the future.

The CUPA survey also provides evidence of the impact of collective bargaining on faculty salaries. Of the public institutions surveyed, 35 percent have collective bargaining agreements. According to the CUPA data, faculty at those institutions earn significantly more than their colleagues elsewhere. Overall, faculty at collective bargaining institutions earn 13.3 percent more; history faculty at those institutions average 16.9 percent more than their counterparts elsewhere, earning $46,252 compared to $39,564. Significantly, the difference between salaries at the two groups of institutions narrowed in 1990–91, from 20 percent to 16.9 percent.

For gender differences, we must return to the AAUP study, which indicates that men earn on the average 8 to 13 percent more than women, depending upon rank, a difference that cannot be fully explained by age or differences in experience. More significant, according to AAUP, is evidence that female faculty are more heavily concentrated than male faculty in lower-paying institutions and fields. Since AAUP does not provide discipline-specific data, however, we must look elsewhere for data on history salaries broken down by gender. The 1989 profile of humanities doctorates compiled by the National Research Council (NRC) indicates that the largest gender gap in income in the humanities remains in United States history, where the mean annual salary (12 months) for males is $48,300 compared to $40,900 for females, a difference of $7,400. Thus females who specialize in U.S. history currently earn84.7 percent of that earned by their male colleagues, a sizeable difference but significantly less than reported in the previous biennial study (76.2 percent). The gap for historians in other specializations is $6,700, smaller than in U.S. history but larger than reported two years before ($4,500) and larger than in any other humanities field. The difference between salaries for male and female faculty narrows if you compare individuals with comparable seniority (year since receipt of degree). But since more males occupy higher-paying tenured positions (71.9 percent) compared to females (49.7 percent), the average salary figure for males overall significantly exceeds that for women.

For more information, consult “The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession,” 1990–1991,” Academe (AAUP), March–April 1991; 1990–91 National Faculty Salary Survey by Discipline and Rank (Washington, DC: CUPA, 1991), v.1, Private Colleges and Universities, and v. 2, State Colleges and Universities. Special studies and tabulations can be purchased through both sponsoring organizations. Contact the AAUP, 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 500, Washington, DC 20005, 202n37-5900; and CUPA, 1233 20th Street, NW, Suite 503, Washington, DC 20036, 202/429-0311. For National Research Council data. see Humanities Doctorates in the United States: 1989 Profile (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1991), available through the Survey of Doctorate Recipients Project, NRC, 2101 Constitution Avenue, NW, Room GR 410, Washington, DC 20418.