Many universities in the United States are reckoning with their own involvement in the history of American slavery. What can historians contribute? It may seem counterintuitive to ask what historians can bring to the discussion of what seems to be an essentially historical problem, but the answer is not obvious because it depends on the tricky relationship between the past and the present.

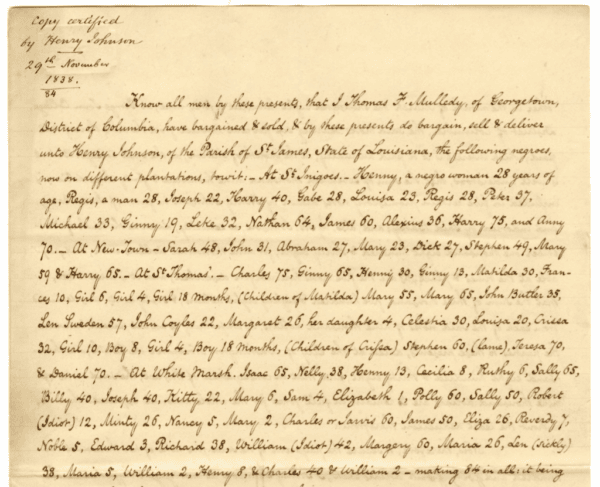

Extract from Bill of Sale for 84 Slaves from Thomas Mulledy to Henry Johnson, November 29, 1838. Georgetown Slavery Archive

This is not an academic question for me. My own university, Georgetown, has been in the public eye recently for its sordid connection to the sale of more than 200 men, women, and children in 1838. These people were the property of the Jesuits of Maryland, who were supposed to care for their souls, but sold them into the Deep South instead. Why? To divest themselves of an unprofitable and controversial labor system, as well as to raise money for their cash-strapped educational mission.

Spurred by misgivings about having a building on campus named after Thomas Mulledy, SJ, the Georgetown president who conducted the sale, Georgetown’s current president Jack DeGioia convened a university Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to study and reflect upon the university’s history and to recommend steps to make amends. The group includes representatives from the administration, faculty, students, and alumni.

Historians are well represented; there are four history faculty in the group, including the chair, David Collins, SJ, and one senior history major, Matthew Quallen, who wrote a series of well-researched and beautifully composed articles in the student newspaper last year, which woke up the current crop of Hoyas to our university’s origins in slavery. I’m a member, as are my colleagues in the history department, Maurice Jackson and Marcia Chatelain.

For this entire academic year, we have been grappling with the past while under pressure from the present. We were prodded by student protests last fall and national media attention this spring. One thing is clear: history has the capacity to ignite strong emotions and demands for justice that challenge the norms of “objective” scholarship.

I hold onto the idea that the first step in “truth and reconciliation” is truth. It’s a quaint notion, truth, but an indispensable one. We must make an effort to figure out what actually happened and make it known. This is where historians can be most useful. This is what we do. But we could do it better, especially the “make it known” part. We need new ways to tell old stories.

Georgetown’s roots in slavery were not a secret before this year. Scholars had written about it. R. Emmett Curran’s outstanding history of the university does not shirk it, and Thomas Murphy, SJ’s Jesuit Slaveholding in Maryland digs deeply into the Jesuits’ religious economy. In the 1990s, the university’s American Studies program made this history part of its curriculum, and developed a pioneering website called the Jesuit Plantation Project, which recently fell victim to upgrades in the university’s web architecture. Digitization is not preservation.

More recent historical scholarship has inspired renewed attention to slavery in our own backyard. Especially important is Craig Steven Wilder’s justly lauded Ebony & Ivy, which shows early American universities’ debts to slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. Seldom is the link between power, wealth, and knowledge so clear. New scholarship on 19th-century American slavery has also clarified the importance of the domestic slave trade to the Upper South, and raised the possibility of tracing the lives of people who were sold to the Deep South. It is here that history meets genealogy.

The achievement of Rachel Swarns’s stunning April 16, 2016, New York Times article is to put a human face on the history of American slavery, and in so doing, to close the gap between past and present. To know that Maxine Crump of Baton Rouge is the great-great-granddaughter of Cornelius Hawkins, whom the president of Georgetown sold to Louisiana in 1838 for roughly $422 to rescue his college from debt, is to raise the moral stakes of the meaning of this history. It is proper to ask, as the New York Times did, what Georgetown owes to her and the other descendants who are alive today.

But it is also here where history, and historians, fall short. We can explain what happened, but we have no special insight into the moral and political questions of what should be done to make amends. What kind of memorials are appropriate? Should Georgetown offer scholarships to descendants? I have ideas, of course, but they come less from my training as a historian than as a concerned citizen with his own views of the requirements of justice.

As a scholar with expertise in the history of slavery, I do feel that my professional obligation is to do what I can to make this history known as truthfully as possible and to explain it as best I can. For me that means returning to the archives. Building on the work of the Jesuit Plantation Project, the working group has launched the online Georgetown Slavery Archive to make significant documentary material accessible to the public, including descendants who are trying to trace their family trees.

While important and revealing, the archival material housed in the Georgetown library and other repositories does not tell the whole story. What is missing from these records is the perspective and voices of people like Cornelius Hawkins, who was only 13 years old when he was shipped off to Louisiana in 1838. In all likelihood his perspective will never be recovered; slavery was a historical silencer. But we can work to include the knowledge and perspective of the descendants in the retelling of this history. That is the least that Georgetown owes them.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Adam Rothman is associate professor of history at Georgetown University, author of Beyond Freedom’s Reach: A Kidnapping in the Twilight of Slavery, and a member of Georgetown’s Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation. The opinions expressed here are solely his own; he does not speak for the working group or Georgetown University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.