Editor’s Note: This article and the following one by Robert Harris were originally presented at the AHA’s 1998 annual meeting at a session sponsored by the AHA Teaching Division. The session was on the AHA pamphlet series, Teaching Diversity: People of Color, developed by the Committee on Minority Historians and edited by Nell Painter (Princeton University) and Antonio Rios-Bustamante (University of Wyoming). The Teaching Division organized the session because it believed that the pamphlet series raises important teaching issues.

In the fall of 1997, I taught a course in US history since 1945 for the first time. Given that I have had a great deal of experience teaching women’s history, one might expect that it would be a relatively simple matter for me to create a new course with gender as a central concept. What I found, however, is that doing so was quite difficult. This was the case in part because I thought it was important to cover much of the material that conventionally dominates such courses, including politics and diplomacy. These topics have not benefited from the amount of scholarly work using gender as a primary analytic framework that my ambitions for the course required. In these fields, some scholarship uses gender effectively as an analytic frame, some provides evidence that enables such an analysis, and some challenges us to rethink materials presented in ways that do not easily fit such a frame. At their best, the available textbooks reflect the state of the scholarship in this area.

As I note in the pamphlet Teaching in United States History (published by the AHA), gender can have various meanings. Most academics understand it as the social relations of the sexes, but may differ in their understandings of how these are constructed and how they operate in relation to a wider context. Most students are confused, with many associating the word with biological sex differences. I begin by talking about and providing various definitions, but emphasizing that in my courses gender is understood as a social relation constructed in interaction with other social relations and cultural meanings and that gender constructs men’s lives as much as it does women’s. I also make an effort to enable students to begin examining the ways that normative understandings of gender affect class formation and identities, racial identities and politics, public policies and private lives. In social history, they assume that race and gender present themselves in some kind of pure form unconnected to each other and other social relations. Finally, many Americans today deny social class altogether or associate it only with racial ethnic groups. As a result, using a complex definition for gender in the course requires care in its development.

Students are often unfamiliar with and somewhat resistant to the application of gender theory to interpretations of the motivations and actions of powerful men. They are generally more comfortable with explanations in political and diplomatic history that rest entirely on such things as partisan politics, ideological commitments, or national interests. It is particularly important for students to understand that the values, institutions, and activities of men have been profoundly shaped by gender. As Anthony Rotundo has noted, “many of our institutions have men’s needs and values built into their foundations, [and] many of our habits of thought were formed by male views at specific points in historical time.”1

In my course, I was not able to do all of this very systematically, particularly in reference to interpreting the actions of powerful men in politics and diplomacy. I did get started in that direction, however. The following discussion examines the possibilities and difficulties of using gender in two subject areas: public policies, families and race in postwar America and the postwar national security state, cold war politics, and the origins of the Vietnam War. It also makes note of some films that might assist in presenting these topics.

Public Policies, Families, and Race in Postwar America

I begin this section with an analysis of the 1935 Social Security Act and its creation of diverse forms of entitlement that reflected and helped to form various relations to the labor market and the state for different social groups. Specifically, the bill created a system of unemployment compensation and retirement pensions intended primarily for male breadwinners and the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program intended for children who lacked a male breadwinner. Always understood as a program for dependent women and children, ADC was expanded to include the primary caretaker and renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) in 1950. The unemployment compensation program and pensions programs did not include the means and morals testing that characterized ADC from the beginning. The inclusion of employee and employer contributions to the funding of unemployment compensation and pensions and the association of their beneficiaries with wage work and breadwinning enabled these programs to avoid the social stigma that came to be associated with AFDC. At the same time, the unemployment compensation and pension programs excluded agricultural workers, domestic servants, and other workers from their coverage. These occupations included very large proportions of racial ethnic men and women, ensuring that the “respectable” domains of Social Security would disproportionately benefit whites as well as men.2

While recipients of Social Security pensions and the program itself were politically unassailable, “welfare” (AFDC) and its recipients came to be demeaned as parasitic and socially dangerous women who bore children to scam the taxpayers. When amendments to the Social Security Act were passed in 1939 transferring the widows of men covered under the act out of AFDC and into other dependents’ categories, the association of AFDC with never-married mothers and racial ethnic groups (who were a minority of its recipients) was further solidified. The government’s policy of supervising AFDC recipients’ sexual morality reflected its conviction that the children for whom the program was designed should benefit only if their mothers remained celibate. These moral concerns escalated in the 1940s and 1950s when AFDC benefits were extended to large numbers of racial ethnic women.

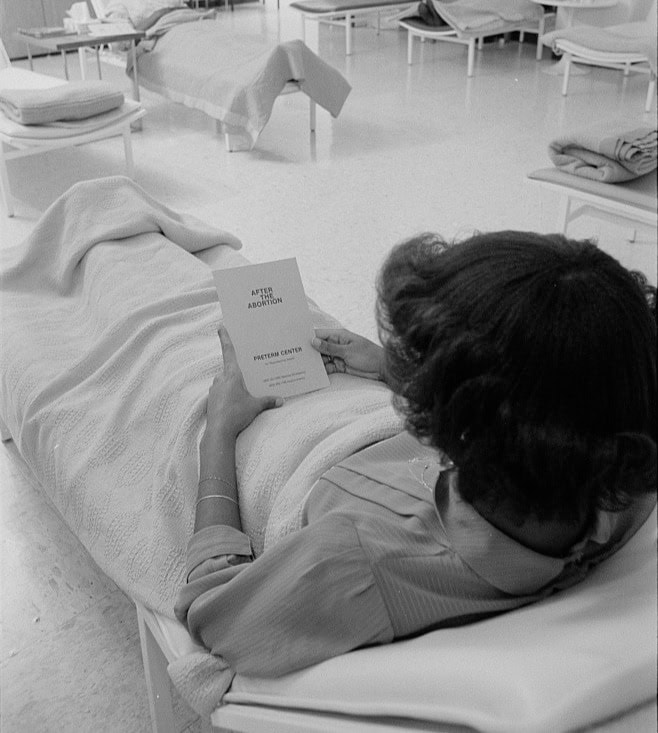

As Rickie Solinger has documented, postwar officials’ policies with regard to racial ethnic women’s unwed pregnancies differed markedly from those they devised for unmarried pregnant white women. Motivated by an increasing demand for babies for white couples experiencing infertility, officials encouraged and sometimes coerced white women to give up their babies for adoption.

In order that these women might later form respectable marriages and nuclear families, they also advised that they remove themselves from their communities during their pregnancies, seek therapy for the neuroses that ostensibly caused them to get pregnant, and thereby complete a process of penance and rehabilitation that would fit them for proper white womanhood in the postwar era. These policies rendered white women’s illegitimate pregnancies socially invisible and eliminated many potential white recipients of AFDC by separating the mothers from their children.

When confronted with unmarried African American women, officials made no attempt to “rehabilitate” them for future marriages and assumed that the women would keep their babies. When a minority of these mothers applied for support from AFDC, their sexual transgressions and their dependence on state assistance became highly visible and elicited high levels of public condemnation. In the 1950s, southern whites fighting to retain racial segregation and white privilege used the crusade against African American AFDC recipients to discredit black efforts to secure equal citizenship and equal educational and economic opportunities. Racialized public policies, therefore, shaped gender and family relations and assumptions regarding appropriate gender and family relations shaped public discourses regarding civil rights.

By the 1960s, some liberals joined those who interpreted African American claims to empowerment through the lens of gender. Interpreting all families without a male head as dysfunctional and socially dangerous, the proponents of Daniel Moynihan’s 1965 Labor Department report, “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” shifted the national focus from employment and other forms of discrimination to shortcomings in black communities that ostensibly derived from inadequate masculine authority in families. As early as 1963, the military had devised Project 100,000 to provide “affirmative action” to racial ethnic men whose poor educational backgrounds had previously disqualified them from service. By 1965, when President Lyndon Johnson escalated the war in Vietnam, the educational enhancement provisions of this program were abandoned and it served as one of several props for the formation of a working-class military to fight that war.3

Gender and the Formation of a National Security State

In the postwar period, American policymakers created a national security state premised on a heightened sense of external and internal threat. This, in turn, led to extraordinary public expenditures on the military and the construction of an elaborate internal security apparatus designed to repress perceived threats to internal order. The effects of the national security state extended into everything from civil liberties to economic structures, from popular culture to political culture. Attempts to discern who was a “real” American and who was a subversive—which took different forms in different eras—shaped social relations, economic opportunities, partisan politics, and foreign relations. Moreover, these debates about political order and social order derived much of their power and substance from their connections to the politics of gender and sexuality.4

The most systematic scholarship on gender and the national security state focuses on the cold war and anticommunism. Anticommunism combined various fears into a cultural package that was very appealing to many Americans; so appealing that it justified systematic denials of civil liberties in order to protect the body politic and a particular definition of Americanism. Moreover, this set of beliefs intertwined fears of domestic political subversion and foreign aggression with anxieties about the maintenance of domestic social and sexual order. The countersubversive rhetoric associated with McCarthyism linked behavior that undermined normative gender relations with behavior that subverted the proper political relations of American society.

Advocates of conventional gender roles advanced the idea that women who were subordinated and domestic produced happy and patriotic husbands and sons who would have the masculine strength to fight against the enemies of capitalism at home and abroad. Therefore, they argued, women who worked for pay or who were sexually active outside of marriage threatened the domestic foundations of America’s international and economic strength. Even women who confined themselves to the domestic roles prescribed for them could pose a danger for the social and political order, however. Even worse than working mothers were those domineering and overprotective mothers whose inappropriate authority over their sons and husbands threatened individual and national emasculation. cold war-era films from My Son John to Rebel without a Cause reinforced the idea that men’s authority in families constituted a bulwark against domestic subversion and disorder. Indeed, teachers might devise a film assignment requiring students to examine films from this period for the ways that they connect ideas about gender order and social order.

In the late 1950s, the US military produced a training film for new recruits entitled Red Nightmare. I was able to use it in my class because I could borrow a copy from a colleague. Narrated by Jack Webb, the film projected the conviction that resistance to communist subversion required domestic patriarchal authority. Depicted in the opening scenes as being uninterested in community involvement, the film’s protagonist awakened one morning to find that the communists had taken over his small American town. Not only that, his wife and children had turned against him, giving their loyalty to the new state rather than to the patriarchal family he represented. His wife ultimately testified against him in the summary trial that led to his conviction for treason. Given the choice of death or subordination to the new order, he chose death. He awakened from his nightmare at the moment of execution. Not surprisingly, he had become determined to stand up to the communist threat apparently in his midst. Gender operated in other aspects of cold war politics and culture as well. As Elaine May has documented, many Americans came to believe that women’s domestic skills would provide a refuge from the stresses and dangers of the nuclear age while masculine authority in the family would act to prevent domestic subversion and external threat. At a time when the United States depended primarily on a politics of nuclear deterrence in foreign policy, civil defense authorities’ stress on home bomb shelters enabled policymakers to obscure the risks and costs of the policies they were pursuing. By deploying a peaceful and safe domestic imagery associating bomb shelters with “Grandma’s Pantry” and other homey scenes, the authorities hoped to defuse public anxieties and remove nuclear policies from the domain of legitimate political discussion. The film Atomic Cafe contains some rather incredible scenes that document the government’s efforts to domesticate and deny the dangers of nuclear war and radiation in the 1950s.

Robert Dean’s work stresses the centrality of a politics of gender and sexuality to the disputes between conservative anticommunists and cold war liberals (who were also anticommunists) in the 1950s. Competing male elites enacted their battles for institutional power and public policy by using sexuality as a litmus test for both national loyalty and manliness. According to Dean, provincial, conservative “isolationists” whose economic interests were generally based in small- to medium-sized capitalist enterprises, a protected domestic market, and the direct purchase of labor power sought to wrest power from the metropolitan internationalist bankers, lawyers, and others who dominated the foreign policy establishment. These conservatives, who generally aligned with Joseph McCarthy, tended to target Ivy League-educated, socially and politically well-connected individuals associated with the Roosevelt-Truman administrations in the hope of discrediting New Dealers and internationalists by calling into question the loyalty and legitimacy of those people, ideas, and policies associated with them.

They did so by using narratives of masculinity that simultaneously enabled them to label their adversaries effeminate while expressing the sense of political dispossession and impotence they experienced when confronted with the power of an upper-class, eastern-educated, internationally oriented elite. To these anticommunists, the class position of their adversaries signified their vulnerability to an enervating and feminine privilege that would weaken America’s global position. Conflating treason and weakness, they claimed that upper-class privilege had rendered the men they opposed effete, weak, and dangerous to the republic. Their narratives of masculinity, which resulted in systematic purges of homosexuals from government positions, were used to establish the political legitimacy of their brand of anticommunism.

A desire to undermine these representations in order to establish manly credentials in domestic and international politics led the cold war liberals associated with the administration of President John F. Kennedy to adopt policies designed to demonstrate the nation’s masculine resolve in cold war confrontations. From the Peace Corps to the resurrection of the Special Forces in the US Army, New Frontier policy initiatives stressed martial values and the rejection of western material comforts. The latter were associated with the feminine domain of consumption and with effete upper-class privileges. To counter them, officials stressed the importance of masculine austerity, heroism, and educated pragmatism for effective global leadership by American diplomats, military leaders, and politicians.

Counterinsurgency in particular provided the Kennedy administration with an alternative to mass military mobilization that was congruent with the president’s “unconventional warrior” ideal of masculinity. Kennedy was confident that covert and guerrilla operations would enable the United States to contain and even roll back global communism. The policies he initiated in Vietnam (and elsewhere) constituted a direct expression of these masculine ideals.

Because gender operates in so many domains of history—politics, social relations, cultural forms, diplomacy—and often links them in interesting ways, it offers a means to integrate the various subfields that we try to cover in survey courses. As the scholarship in this area grows, the task will become easier. In the meantime, we can supplement the secondary scholarship with films, personal narratives, and other kinds of primary sources to engender postwar history.

Notes

- Karen Anderson, Teaching Gender in US History (Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association, 1997); Anthony Rotundo, American Manhood: Transformations in Masculinity from the Revolution to the Modern Era (New York: Basic Books, 1993), 9. [↩]

- The discussion in this section draws from Linda Gordon, Pitied But Not Entitled: Single Mothers and the History of Welfare, 1890–1935 (New York” Free Press, 1994); Rickie Solinger, Wake Up, Little Susie: Single Pregnancy and Race before Roe v. Wade (New York: Routledge, 1992); Karen Anderson, Changing Woman: A History of Racial Ethnic Women in Modern America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996); Winifred Bell, Aid to Dependent Children (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965); and Jill Quadagno, Tile Color of Welfare: How Racism Undermined the War on Poverty (New York Oxford University Press, 1994). [↩]

- Christian Appy, Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993); US Department of Labor, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (Washington, D.C.: U.S. GPO, 1965). [↩]

- The discussion in this section draws from Elaine Tyler May, Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era (New York: Basic Books, 1988); Robert Dean, “Masculinity as Ideology: John Kennedy and the Domestic Politics of Foreign Policy,” Diplomatic History 22 (winter 1998), 29-62; Robert Dean, “Manhood, Reason, and American Foreign Policy: The Social Construction of Masculinity and the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations,” PhD dissertation, University of Arizona, 1995; the H Diplo discussion of Dean’s Diplomatic History article at http://h-net2.msu.edu/ ~diplo/Dean.htm; and Michael Paul Rogin, Ronald Reagan, the Movie and Other Episodes Political Demonology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 236-71. [↩]

Karen Anderson teaches at the University of Arizona. She is the author of Changing Woman: A History of Racial Ethnic Women in Modern America and the AHA pamphlet, Teaching Gender in US History.