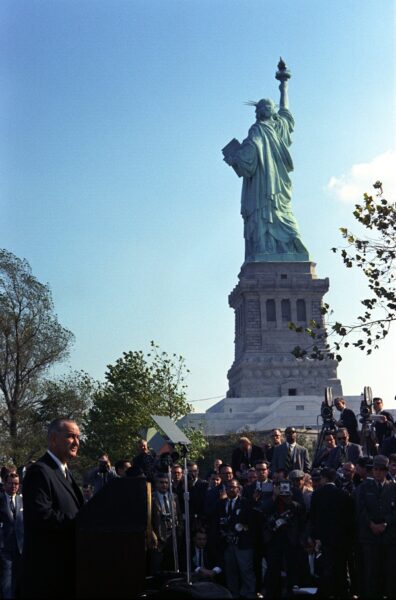

President Lyndon Johnson signed the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act at the Statue of Liberty. Wikimedia Commons

In my little corner of the world, there was quite a ruckus in August 2016 when Fredrik Logevall and Kenneth Osgood complained in the New York Times about “the end of political history.”1 I will not repeat the strong arguments that various historians made about the column’s flaws—the false claims about the number of job advertisements in political history, the failure to recognize the field’s vitality (even narrowly defined), and the constrained definition of politics.2 Similarly valid responses could focus on the centrality of political history in survey courses and textbooks. Here I want to offer a perspective rooted in my little corner of the world, which is filled with historians of sexuality who work on politics and historians of politics who work on sexuality.

I have had the great fortune of working as a professor at York University (in Toronto) and San Francisco State University. I was hired at the former as a US political historian and at the latter as a historian of US constitutional law. My first book was a study of Philadelphia gay and lesbian politics from 1945 to 1972. My second examined US Supreme Court decisions on sex, marriage, and reproduction from 1965 to 1973. My third was a synthetic account of the US gay and lesbian movement from 1950 to 1990. I have taught many courses on the history of gender and sexuality, many on the history of politics and law, and some that address all four. Imagine my surprise when I read one of Logevall and Osgood’s explanations for the “disappearance” of political history: “The movements of the 1960s and 1970s by African-Americans, Latinos, women, homosexuals, and environmental activists brought a new emphasis on history from the bottom up, spotlighting the role of social movements in shaping the nation’s past.”

“Homosexuals”? I was not the only historian to notice the outdated reference. But the use of old-fashioned and scientific language was not the only indication of trouble.3 More problematic, from the perspective of my little corner of the world, was the fact that their formulation erased the work so many have done to integrate political history with the history of social movements and the history of race, gender, and sexuality.

My library is filled with books and articles that address political history (narrowly defined) in relation to the history of sexuality, not to mention political history in relation to the histories of gender and race. These include works by Thomas Foster and Martha Hodes on the late 18th and 19th centuries; Peter Boag, David Langum, Kevin Murphy, and Ruth Rosen on the Progressive Era; George Chauncey, Blanche Wiesen Cook, Andrea Friedman, and Daniel Hurewitz on the early 20th century; Allan Bérubé, Leisa Meyer, and Michael Sherry on World War II and the military; Douglas Charles, David Johnson, and Claire Potter on the Red and Lavender Scares; Christopher Agee, Martin Duberman, Marcia Gallo, David Garrow, and Whitney Strub on the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s; and Jennifer Brier, Finn Enke, Gillian Frank, Christina Hanhardt, and Emily Hobson on the 1970s and 1980s. Then there are works that cover multiple periods, including books by Nan Alamilla Boyd, Allan Brandt, Margot Canaday, John D’Emilio, Lisa Duggan, William Eskridge, Estelle Freedman, Linda Gordon, John Howard, Kevin Mumford, Peggy Pascoe, Leslie Reagan, Robert Self, Timothy Stewart-Winter, and Leigh Ann Wheeler.

Many historians noticed Logevall and Osgood’s erasure of this work, but so far I have not seen any commentary in print that relates this problem to one that was evident in another New York Times column, published just a day before Logevall and Osgood’s. Journalist Kevin Baker’s “Living in L.B.J.’s America” seems to represent the kind of political history that Logevall and Osgood favor—it focuses on a US president and his legislative achievements.4 In discussing the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, Baker quotes Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 State of the Union address, which declared:

We must . . . lift by legislation the bars of discrimination against those who seek entry into our country, particularly those who have much needed skills and those joining their families. In establishing preferences, a nation that was built by the immigrants of all lands can ask those who now seek admission: “What can you do for our country?” But we should not be asking: “In what country were you born?”

Praising Johnson for his political success in achieving this major reform (and ignoring the advocates who insisted that the legislation would not fundamentally change the racial composition of the United States), Baker writes, “Immigrants would finally be admitted to the United States without consideration of their race, ethnicity or country of origin.” This is not quite true and Baker knows it; he acknowledges that the 1965 law imposed a cap of 120,000 immigrants a year from the Western Hemisphere. Nevertheless, he quickly returns to his main point: “The greater principle was established.” As for what that principle was, Baker turns to the words of LBJ historian Randall Woods, who has written that the law “did nothing less than ensure that America remained a land of diversity whose identity rested on a set of political principles rather than blood and soil nationalism.”

Except this is not quite true either. And here is where I want to return to the problem of creating artificial distinctions between political history and the history of sexuality. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act removed the restrictive national origins system that had been in place for more than four decades, but it also was the first US immigration law that explicitly barred people with “sexual deviations.” To be sure, “sexual deviates” had been excluded under other statutory provisions: various laws barred individuals who were likely to become public charges, those who had committed crimes of “moral turpitude,” and those who were “afflicted with psychopathic personality.” But the 1965 law—passed in the wake of the 1964 resignation of LBJ aide Walter Jenkins after he was caught having sex with a man in a public bathroom—more overtly declared that individuals classified as having “sexual deviations,” generally understood to include “homosexuals,” were to be excluded.

In 1967, the Supreme Court read this intention back into the earlier “psychopathic personality” provisions of immigration law when it upheld the deportation of Clive Boutilier, a Canadian “homosexual” who had been living as a legal resident in New York for many years. And it’s not as though the sexual politics of the 1965 immigration legislation are now an obscure footnote: they have been discussed by at least four US political historians—Margot Canaday, Martha Gardner, William Turner, and me—and analyzed by scholars in legal studies, American studies, and ethnic studies, including William Eskridge, Eithne Luibhéid, Shannon Minter, Susana Peña, and Siobhan Somerville.

There’s more. Political historians generally describe the 1965 law as replacing a system that restricted immigration based on national origins with one that gave preference to family members of US citizens and legal residents, along with individuals who had professional and specialized skills needed by the United States. Unless they are also historians of gender and sexuality, however, political historians do not generally comment on the gender and sexual implications of a system that granted preferences to spouses and other family members. (We might refer to this as a system of “blood nationalism.”) In a world that denied legal marriage to same-sex couples and placed an array of obstacles in the paths of individuals who did not have or were estranged from or in conflict with politically recognized spouses or politically recognized families, the implications were potentially grave.

The 1965 immigration law was a major piece of legislation that accomplished many positive and important things. But in my little corner of the world, which includes a large number of US political historians, this law was also a political manifestation of larger dynamics that established, maintained, and strengthened the supremacy of family, heterosexuality, and marriage in the United States. And if we cannot recognize that this is and was political, the future of political history is dire indeed.

is the Jamie and Phyllis Pasker Professor of US History at San Francisco State University. He is the author of City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia (2000), Sexual Injustice: Supreme Court Decisions from Griswold to Roe (2010), and Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement (2012).

Notes

1. Fredrik Logevall and Kenneth Osgood, “Why Did We Stop Teaching Political History?” New York Times, August 29, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/29/opinion/why-did-we-stop-teaching-political-history.html?.

2. See Mary L. Dudziak, “Political History Is Alive and Well, and Matters More Than Ever,” Balkin.com, August 30, 2016, https://balkin.blogspot.com/2016/08/political-history-is-alive-and-well-and.html; Roy Rogers, “The Strange Death(?) of Political History,” The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History, September 9, 2016, https://earlyamericanists.com/2016/09/09/the-strange-death-of-political-history/; Gabriel Rosenberg and Ariel Ron, “Chill Out: Political History Has Never Been Better,” Lawyers, Guns & Money, September 1, 2016, https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2016/09/chill-out-political-history-has-never-been-better; Julian Zelizer, “Political History Is Doing AOK,” Process: A Blog for American History, August 31, 2016, https://www.processhistory.org/zelizer-political-history/.

3. See Jeremy W. Peters, “The Decline and Fall of the ‘H’ Word,” New York Times, March 21, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/23/fashion/gays-lesbians-the-term-homosexual.html.

4. Kevin Baker, “Living in L.B.J.’s America,” New York Times, August 28, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/28/opinion/campaign-stops/living-in-lbjs-america.html”

Marc Stein is the Jamie and Phyllis Pasker Professor of US History at San Francisco State University. He is the author of City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia (2000), Sexual Injustice: Supreme Court Decisions from Griswold to Roe (2010), and Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement (2012).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.