I admit it: I stalk dead drug traffickers in libraries, archives, newspapers, databases, films, photos, literature, and documents. One of my favorite tools, however, is the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), which is turning 50 years old on July 4, 2016. While the FOIA is useful for historians, over the years I have found that it takes substantive prior research for a request to be successful or for it to prove an asset for a historical project.

Throughout my career, I have relied on the work of other scholars who have used FOIA. The National Security Archive (NSA), an online repository of declassified documents obtained through FOIA requests, is a valuable resource for scholars looking for archival materials as well as information on how to navigate the process. For years, I have used the archive’s primary source materials in my classes, and for the novice user, the NSA website provides information on filing a FOIA request and following the process through with an appeal.

After filing a request, I eagerly await the package containing the documents—opening it can feel like unwrapping a present. Even though I can never be sure if it will contain what I wanted, and the materials I receive are, more often than not, incomplete, I am always content to have it. The documents usually offer a snapshot of the past that must be further positioned and analyzed by the historian—they provide no great narrative or smoking gun. Furthermore, depending on their nature, requests can often take months or years to be processed, especially if the records concern people who might still be alive. For example, a request I submitted over two years ago is still listed as active on the Drug Enforcement Administration website. Scholars looking to submit FOIA requests should take the time to peruse lists of annual FOIA submissions that are available on government agencies’ websites, including that of the Department of Justice—if someone has previously requested similar information, the process could take less time compared to when requesting materials for the first time.

Why did FOIA emerge? Then-congressmen John Moss (D-CA) and Donald Rumsfeld (R-IL) recognized the need for greater governmental transparency due to increased secrecy during the Cold War. FOIA gives US citizens the right to know their government and its actions, but there are exceptions to access. Moss worked on the idea of greater transparency from the mid-1950s, and it took over 10 years of advocacy before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the act on July 4, 1966. A man known for his boisterous ways and public signings of laws, President Johnson signed this piece of legislation privately. Since then, some of the early supporters of transparency, such as Rumsfeld, have lost their youthful idealism. Over the years, FOIA has remained controversial with opposition to amendments and changes continuing under different presidential administrations including that of George W. Bush, in which Rumsfeld served as the secretary of defense.

Despite the ongoing political battles, FOIA remains a useful, if imperfect, tool for historians. Of course, Moss and Rumsfeld probably did not think that over 60 years later a historian in Queens would see it as a tool to get to know deceased drug traffickers and those who policed them. These are people who rarely leave their personal papers to an archive. Yet, I think that most of them knew, at some level, that the US government (as well as Canadian and Latin American governments) created archival materials on them, albeit with a particular ideological slant.

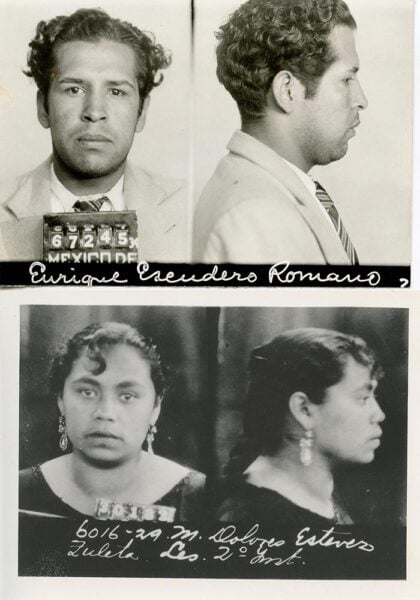

Mug shots of María Dolores Estévez Zuleta and Enrique Escudero Romano, US Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, María Dolores Estévez Zuleta, Freedom of Information/Privacy request 1150736-001.

From filing FOIA requests over the years, I have learned information that has significantly enhanced my research. For example, I had learned a great deal about the drug traffickers Enrique Escudero Romano and María Dolores “Lola la Chata” Estévez Zuleta from archives in Mexico and the United States. Both were recognized drug traffickers, but Lola la Chata was a Mexico City boss of a drug trafficking organization. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) director, Harry J. Anslinger, had put out feelers about possibly extraditing her to the United States in the 1940s. A FOIA report, however, substantiated my belief that policing agents viewed Lola la Chata and Escudero as transnational dangers. Escudero was one of Lola la Chata’s male partners, and agents speculated that perhaps he was her lover. Policing agents in Mexico, Canada, and the United States sought them when it appeared that the pair had crossed into the United States with a carload of heroin destined for Canada. Mexican officials supplied US and Canadian authorities with recent mug shots, fingerprint images, and information that was circulated to different police agencies through all-points bulletins in the Southwest and the Midwest. I also learned that US agents suspected Escudero to be a US citizen. In California, Georgia, and Texas, policing agents investigated Mexican American men with similar names and then detained, photographed, and fingerprinted them in order to compare data with that of Mexico’s information on Escudero.

Since I was not requesting records about myself, in all of my filings, I had to prove that the people involved were deceased or over 100 years old. To do this, I scoured newspapers and death records. This was difficult because drug traffickers frequently used aliases, and many others went into witness protection—it is difficult to find death announcements for those in protected custody. Now, I keep running lists of aliases or suspected aliases for certain traffickers. At times, I have been frustrated by responses to my FOIA requests. For instance, I found files of communications between the FBN and the Federal Bureau of Investigation on a particular 1940s US-based drug trafficking organization (DTO) with extensive contact with Mexican DTOs in the Records of the Drug Enforcement Administration, DEA-BNDD. Yet, when I filed a FOIA request for further information, I was told no such files existed. Of course, proceeding under the assumption that the files must exist, I now have to determine how to revise my request. Over the years I have discovered that a successful FOIA request is always one that is based on good historical research.

Just as Moss struggled over 60 years ago in getting FOIA passed into law, historical research using FOIA takes perseverance. So on this 50th anniversary of the act, I say thank you to Mr. Moss and President Johnson . . . and even begrudgingly to you, Mr. Rumsfeld.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Elaine Carey is the chair of the history department at St. John’s University in Queens, NY. She is the author of the award-winning Women Drug Traffickers: Mules, Bosses, and Organized Crime (2014).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.