On February 6, an AHA webinar, Don’t Say Gay, Stop WOKE, Banned Books, and Anti-Trans Laws: Teaching through the Backlash, brought together several historians to discuss the recent spate of legislation and executive orders that have targeted the teaching of “divisive concepts,” critical race theory (CRT), LGBTQ+ history, and related topics.

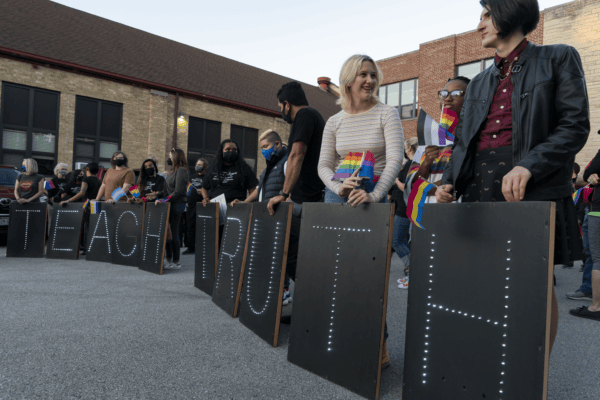

Over the last few years, many parents, students, teachers, and other community members have held protests at school board meetings, including this one in Waukesha, Wisconsin. Joe Brusky/Flickr/CC BY-NC 2.0

In her introduction, moderator Claire Potter (New School) reminded the audience that although it was put together before “the fracas about AP standards in African American studies” in Florida, these controversies are a reminder of how much those who teach African American history and LGBTQ+ history have in common, as well as the connections we must forge with colleagues across high schools, community colleges, and four-year institutions. The panel included three historians working in different contexts. Anita Kurimay (Bryn Mawr Coll.) is a specialist in east central European history and the history of far-right politics. Wesley Phelps (Univ. of North Texas) joined to share his perspective as a teacher of recent US history and queer history in Texas, a state at the forefront of these culture wars. Finally, Jeremy C. Young, a historian and senior manager of free expression and education at PEN America, represented advocates against censorship and for academic freedom across the country and education levels.

Kurimay began by offering the global context. In Hungary and Poland, politicians have been especially successful in enforcing so-called “family values” in education policy. Hungary has banned teaching about sexuality and transgender issues in schools, equating queer sexualities with pedophilia; sex education there now focuses only on education for family life and religious teaching. In Poland, Christian nationalists have not only passed similar legislation on LGBTQ+ issues, but they have also instituted “new national curricula that erase national and individual responsibility for aiding and participating in the Holocaust.” Both countries have made it easier to fire teachers, and they have passed new regulations to curtail teachers’ strikes and protests. Many teachers have had to decide whether they can afford to lose partial income or their jobs entirely to support a more progressive vision of education. Kurimay fears that “Poland and Hungary are not only warning signs but offer a stark picture of where the US is heading in Republican states.”

Phelps argued that state government officials in the United States have used policies in places like Hungary and Poland as “a blueprint”—most visibly in Florida—but he is beginning to see it in his home state of Texas too. In 2021, the Texas legislature approved an anti-CRT bill with the vague language generally characteristic of such legislation. But one section had a clear mandate, he said: “In public school history classrooms, slavery and racism can only be taught as deviations from the founding principles of the United States,” which Phelps said “flies in the face of about 100 years of scholarship.” Texas is waiting until 2025 to make major changes based on this law to the state’s social studies standards, which means “we have from now until then to make our voices heard.”

Hungary and Poland have made it easier to fire teachers, and they have passed new regulations to curtail teachers’ strikes and protests.

According to Young, PEN America has been tracking divisive concepts legislation at the state level since 2020. Through most of its 100-year history, PEN America has focused its efforts on freedom of expression for writers at home and especially abroad. But now, the organization has become concerned with what it calls “educational gag orders”—divisive concepts and anti-CRT laws that grew out of the backlash to the New York Times Magazine’s The 1619 Project and the racial reckoning that took place following the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020. Young and his colleagues have traced more than 270 bills over the last three legislative sessions, with 140 of those being proposed in 2022 alone. In all, 18 states now have such laws on the books, including seven where laws specifically affect higher education. According to Young, PEN America is deeply concerned because the laws’ “vagueness and the strength of the prohibitions and penalties . . . lead to a profound chilling effect. It’s very difficult for teachers and administrators at universities and K–12 institutions to know exactly what is banned. And the understandable impulse is simply to ban any mention of race, gender, and sexuality.” Though 2023 is young, we have already seen a new wave of such proposed legislation, particularly in Florida. On January 31, a week before the webinar, Florida governor Ron DeSantis “proposed a series of laws that would constitute the most draconian restrictions on higher education ever instituted in the United States,” Young said. “We are facing a truly existential threat to higher education.”

The panel then turned to questions from the audience. Are openly gay teachers being purged in Europe and the United States for violating such laws? Kurimay said that 2,000 teachers have been fired in Hungary for not using new federally mandated textbooks or following the new curriculum, but because of the atmosphere there, most LGBTQ+ teachers would be afraid to be out and likely keep their sexual orientation or gender identity private. In Texas, Phelps said the fear is certainly there, but he has only heard anecdotal evidence. PEN America has only heard of one or two firings, Young said. But there have also been some “murky” cases, such as an Oklahoma teacher who was disciplined for sharing the Brooklyn Public Library’s banned books website with her students; she then chose to leave her job. The vagueness of these laws is meant to instill fear, Young argued, and it’s indeed having a chilling effect as teachers choose to self-censor, with “self-censorship and administrative censorship both disproportionately affecting African American teachers.” Yet educators should avoid self-censoring if possible, he emphasized.

The vagueness of these laws is having a chilling effect as teachers choose to self-censor.

Potter raised another question from the audience: How do we engage in discussions about free expression, identity, discrimination, and other topics without playing into conservative rhetorical traps, when the right has claimed freedom of speech as a problem uniquely targeting conservatives in higher education? “We have to understand that there is a difference of scale between a culture of censoriousness,” Young said, “and the actual censorship of speech by the government.” Citing studies on the University of North Carolina and University of Wisconsin systems, Young argued that conservative students’ experience of feeling silenced on campus is primarily a campus climate issue related to social pressure from peers, not a classroom issue. Yet as Phelps reminded the audience, “the kind of speech matters.” There is a distinction, for example, between a difference of opinion and hate speech that denigrates the existence of trans people, potentially harming trans students, faculty, and staff on campus. As Kurimay added, disagreement, debate, and changing your mind are essential parts of education. These issues are all wrapped up together.

The panel concluded with a question about how to explain the value of having multiple voices and perspectives in the curriculum and classroom—an issue that is perhaps at the heart of opposition to “divisive concepts” education laws. Young pointed to the AHA’s 2021 national survey, which showed that the majority of Americans agree that we should learn about aspects of history that make people feel uncomfortable. Children and students grow up to become voters and leaders, and they need to understand people who are like them and who are different from them. As Phelps said, “We need to emphasize this is how knowledge is produced . . . by including a multiplicity of voices.” Kurimay closed the discussion with, “For the next generation of global citizens, the world is only going to become more diverse. . . . It’s crucial that we incorporate different voices, different experiences to try to see where they are coming from.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.