Jonathan Zimmerman

Here’s a quick quiz, culled from this week’s front pages: name an American politician who supports “diversity” in American higher education.

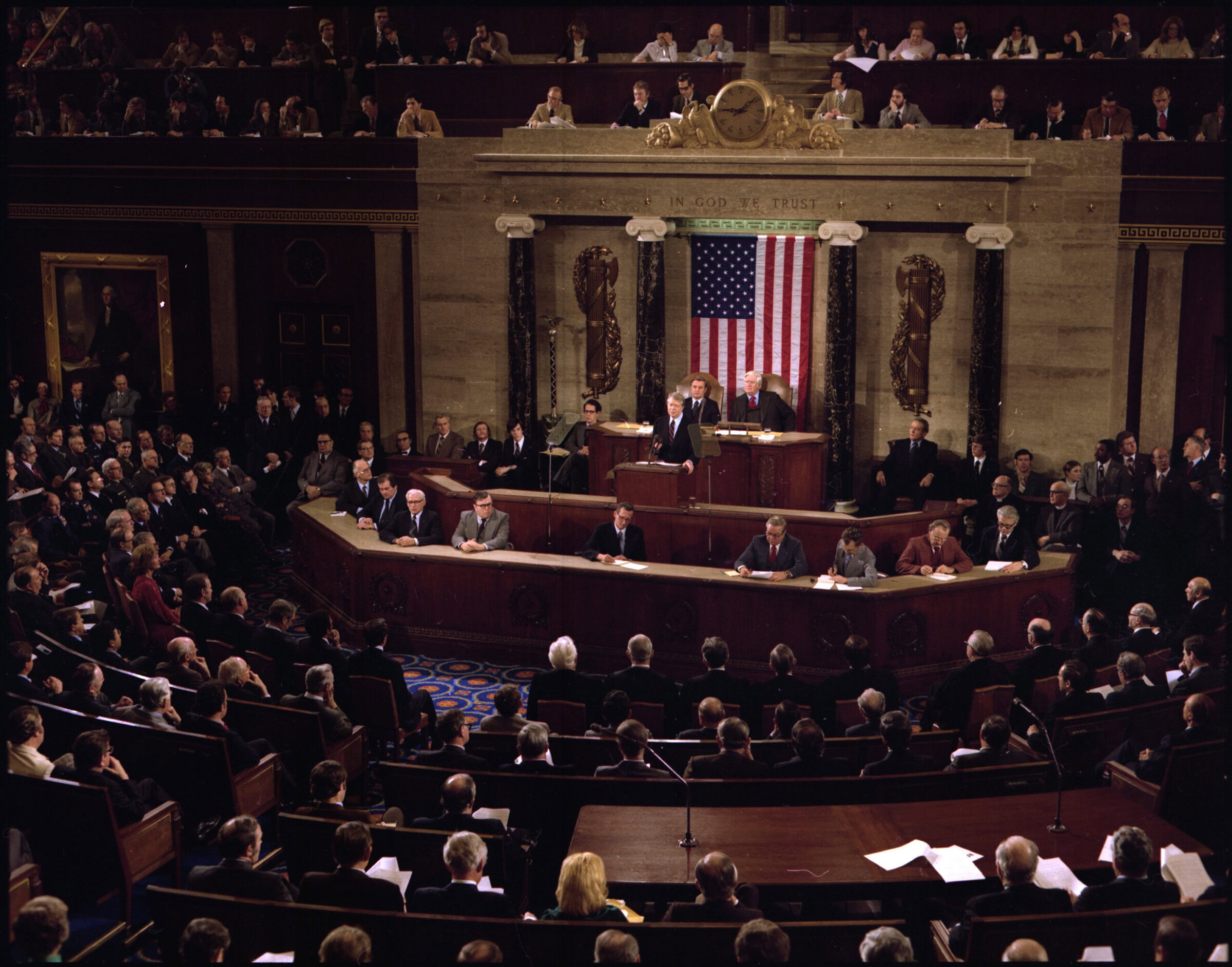

That’s an easy one: almost all of them do. And that’s the major takeaway from Fisher v. Texas, which let stand earlier decisions allowing universities to consider race in student admissions. The real controversy surrounds how to do that, as the Fisher decision also illustrates: the Supreme Court remanded the case to a lower court to see if the University of Texas had complied with prior rulings on the permissible ways for promoting diversity. True, Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas continued to insist that affirmative action-and its diversity rationale-were simply unconstitutional. But theirs was a minority voice, drowned out by the bipartisan chorus of relief that greeted Fisher. Although the means of enhancing diversity remain contested, in short, the goal is mostly shared.

So let’s go on to the next question: name a politician who supports racial integration.

You can’t. From President Obama on down, there isn’t a single major figure who routinely invokes that term. Nobody actively opposes integration-least of all the president, himself the product of richly integrated institutions. But you don’t hear anyone making it a centerpiece of their politics, either. Indeed, “diversity” has replaced “integration” as our central racial motif.

Integration refers to our K-12 schools, of course, and diversity to our colleges and universities. Since the 1970s, our schools have become less integrated, rather than more so: roughly 40 percent of black and Hispanic students now attend schools where 10 percent or fewer of their classmates are white. But there’s no real campaign-even among the tribunes of “diversity”-to reverse the trend.

That’s partly because of this same Supreme Court, which sharply limited school districts’ efforts to achieve racial balance in twin 2007 decisions. But the trend away from K-12 integration was underway long before that. Polls routinely show that Americans of every race want to live, work, and study in integrated environments. But they’re not willing to do the heavy lifting to create those environments, especially in our public schools.

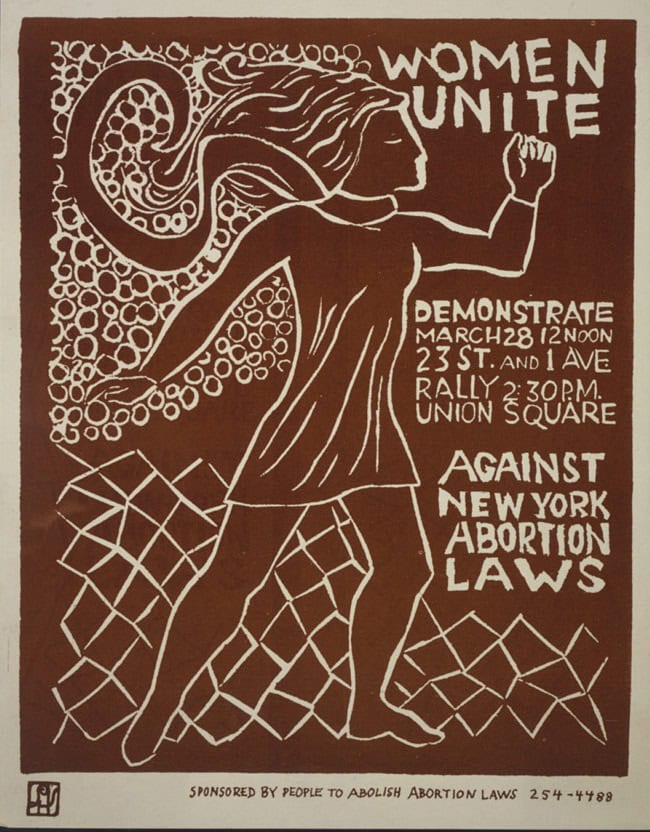

We tried that, the argument goes, and it didn’t work. Court-ordered busing created a right-wing backlash and white flight, hollowing out the inner cities and polarizing the electorate. Even more, integration placed an unfair burden on African Americans. Some of their best schools had to close their doors, and many of their veteran teachers lost their jobs.

That’s the received historical wisdom right now, in many different quarters, and it contains elements of truth. But it’s also hugely flawed, neglecting the enormous benefits that integration brought to African Americans and to the nation as a whole. Every year seems to bring rich new studies of African American struggles and achievements under Jim Crow; we also have a spate of books about the “ordeal” of integration after Brown v. Board of Education, focusing on the heroism of black pioneers and the perfidy of white resistance. But we still lack compelling accounts of how blacks and whites have actually lived integration, in the six decades that have elapsed since then.

We also need to remind Americans how far they have strayed from Brown, which can fairly be called part of America’s civil religion. We all give it ritual obeisance, even as we flout its spirit. George W. Bush and Barack Obama have both invoked Brown v. Board of Education on behalf of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Bush’s signature education reform. But NCLB says nothing-that’s right, nothing-about racial integration. It does require school districts to report their test scores according to race, which has spawned another new language for discussing the subject: “the achievement gap.” But Brown said that segregation itself keeps minority kids behind! If it was correct-and if the segregation of our schools continues apace-then NCLB is destined to fail.

Likewise, supporters of affirmative action wrap themselves in the redolent language of Brown. The modern struggle for racial justice began with Brown v. Board of Education, the story goes, and it continues into Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) and Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), which upheld Bakke‘s diversity rationale. Its latest chapter is Fisher, which left the diversity goal intact even as it questioned our route for getting there.

Please. Brown envisioned children of different races learning together from their earliest years, when kids are at their most impressionable; affirmative action only addresses college students, who are much more fully formed. Brown also said that segregated environments were profoundly harmful, for minorities and for our nation at large. So it was incumbent upon all of us-as a matter of simple justice, as well as of patriotic duty-to create mixed classrooms, particularly in elementary schools.

That’s the vision we need to rediscover. And historians can help, just as they did during the era of Brown v. Board of Education. Back then, scholars such as John Hope Franklin and C. Vann Woodward unearthed the sins and scars of segregation; now we need a new generation of researchers who can demonstrate the salutary effects of integration. The Supreme Court has confirmed that affirmative action in our colleges and universities is a worthy goal, because it helps prepare people to live in a country full of differences. Too bad so many of our public schools don’t.

Jonathan Zimmerman is a professor of history and education at New York University. He is the author of Small Wonder: The Little Red Schoolhouse in History and Memory (Yale Univ. Press).