On November 9, 2022, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Haaland v. Brackeen; a decision is expected in 2023. The case challenges the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), a 1978 federal law that created a framework to strengthen tribal governments’ control over their children, prioritize adoption into the same tribe, and in the process help tribal nations to survive culturally as well as politically. For the children themselves, the law ushered in a reform against the pervasive dislocation of youth from their Indigenous cultures.

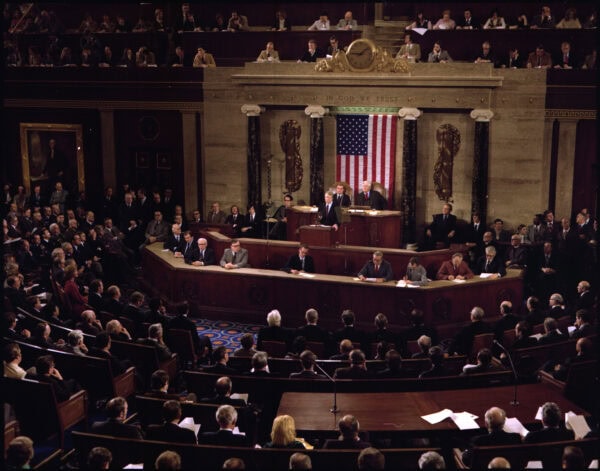

If successful, the recent constitutional challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act has implications at every level of American society.National Archives and Records Administration/Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

The ICWA was written in reaction to a dark history, one which included the systematic kidnapping of children into boarding schools, states’ denial of support to Native children, and the widespread removal of Native children from their families to be placed in white foster homes. For generations, Native children were taken from their nations, families, and cultures. The ICWA attempts—with frequent success—to prevent this. Therefore, a ruling that declares the ICWA to be unconstitutional could do irrevocable damage to Native nations and Native children. This alone is frightening enough.

The ICWA’s survival is the next great bellwether for US democracy—and not just for Native nations. Recently, many have accused the Supreme Court of using selective originalism to undermine democratic norms and popular will in its recent rulings. Dobbs v. Jackson (abortion rights), New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen (gun control), and Justice Clarence Thomas’s threat against gay marriage, gay sex, and contraception are just a few examples, and in each, some members of the court happily cited bad history to make their points.

But as the AHA, the Organization of American Historians, and the NYU-Yale American Indian Sovereignty Project pointed out in their amicus brief for this case, the pseudo-historical cudgel cannot work here. The sweeping plenary power Congress holds over Indian Affairs is originalism. The Constitution’s framers fully intended to treat Native nations as foreign polities—granting Congress almost unrestrained power over relations with them—and there is no escaping that it was the founders’ intent for Congress to wield that monopolistic power forever. In this way, although Haaland v. Brackeen will not capture the national attention in the same way as the cases cited above, it represents an even greater litmus test for the court’s political polarization as seen by its willingness to drop centuries of precedent overnight and thus public perception of its legitimacy.

For generations, Native children were taken from their nations, families, and cultures.

In Native history, we focus more, relatively speaking, on the harms that plenary power wrought within Indian Country, but laws like the ICWA, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (1978), the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975), and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990) are just a few bright examples of genuinely protective laws that have reinvigorated Native culture and nation-building. The ICWA itself represented the moment that Congress, responding to powerful Native activism and the needs of rebuilding Native nations, decided that Native children must not be systematically adopted out of their revitalizing cultures. These laws represented US and Indigenous democracy at its best, demonstrating that an enlightened Congress can be a genuinely protective power for Native peoples and their political nations and wield its democratic arm for constructive rather than destructive policies in Indian Country—regardless of the settler colonial or imperial context. And they show that, during the late 20th century, Congress faced few barriers in its attempts to repair the damage of colonialism, thanks in large part to its plenary power.

Although the court has the power to overturn congressional acts, a decision in favor of Brackeen could call into question at least some of the plenary power explicitly granted to Congress in the Constitution, particularly if the court follows the arguments of conservative elements that dislike these “special rights” (i.e., sovereignty) for Native nations. As the justices pressed the plaintiffs’ attorneys on how far they should go in undermining the plenary power for the sake of “equal protection,” it became apparent that the logical endpoint of their argument would put much of federal Indian law in jeopardy. As Justice Neil Gorsuch criticized this, he added: “We’d be busy for the next many years, striking things down.” The things being struck down, of course, would be a slew of treaty law and legislative reforms.

The third preference has become a target for the conservative justices, who are determined to undermine plenary power and reject the interconnectedness of Native nations.

Fortunately, several justices seemed well-attuned to the sweeping threat to Indian law that Haaland v. Brackeen presents. Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked if the court was really expected to “overrule all of those precedents” of absolute plenary power, while at another point, an incredulous Justice Sonia Sotomayor remarked, “It strikes me as a very odd way to think about plenary power, to just start constructing categories, and saying everything else is left out . . . when we’ve said over and over: ‘everything, except really rare things, are in!’” Much of the court, then, is still uncomfortable with stepping into this legislative territory. However, from their participation in oral arguments, several justices appear to be considering the possibility that Native nations undermine their ideal “color-blind” society—never mind that Native nations are multiracial and multiethnic.

Worse yet, the court already seems determined to repeal the ICWA’s “third preference,” which provides that if a Native child cannot be adopted by a family member or a citizen of their nation, third preference should be given to a citizen of another Native nation. The third preference is straightforward. Different tribes still share culture, language, customs, and a pressing need to revitalize all the above. Congress understood this in 1978 and used its plenary power to create the ICWA’s three-pronged framework. But the third preference has become a target for the conservative justices, who seem determined to undermine plenary power and reject the interconnectedness of Native nations. Justice Barrett remarked that ICWA’s third preference rendered tribes “fungible.” On this dangerous path, the Supreme Court may force the end or scaling back of the ICWA by ignoring centuries of precedent, dismissing what the people’s lawmakers have given us, and abandoning a portion of the court’s professed commitments to originalism in the process. Against the odds, democracy gave us the ICWA, but its continued existence—which should be uniquely safe from the court’s recent boldness—is no longer guaranteed.

This makes Haaland v. Brackeen a monumental bellwether for US democracy—not just Native peoples. In some ways, this situation feels fitting. A Native sovereignty case that stretches back to this country’s earliest founding—more than anything else—can tell us precisely how far the Supreme Court will go in undermining congressional power, and by extension, our democracy.

Noah Ramage (Cherokee Nation) is a PhD candidate in history at the University of California, Berkeley.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.