A historian whose work has been primarily engaged with New Deal-Fair Deal liberalism will likely view the Hobby Lobby decision and the reaction to it as proof that the character of political liberalism has changed so greatly from that of the 1930s and 1940s that it would be barely recognizable to Roosevelt and Truman—Truman’s support of a national healthcare program notwithstanding.

The liberalism of the middle years of the 20th century (roughly 1933–63) predominantly concentrated on issues of economic distribution and only tangentially addressed cultural mores. Contraception, although widely practiced with the limited means available in that era, was seldom a matter of public discussion or even polite conversation. It was not until 1965 that the Supreme Court, in Griswold v. Connecticut, struck down a Connecticut law prohibiting the sale or use of birth control devices—and did so by finding a shadowy right of privacy in “penumbras formed by emanations” from the Bill of Rights. Many of its supporters felt the decision stretched prevailing standards of constitutional interpretation, but nonetheless embraced it as necessary and liberating. Roe v. Wade followed in 1973 and rested on that same implicit right of privacy.

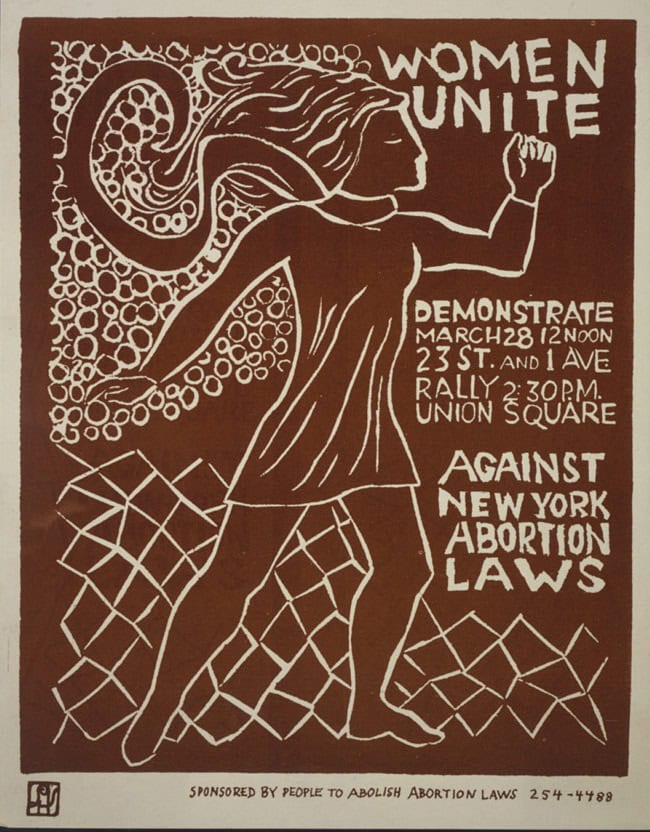

It surely was not a coincidence that the Griswold decision was handed down at a time when the contraceptive pill was becoming widely available and an emerging feminist movement was challenging traditional mores. It and Roe demonstrate that the Court frequently follows social trends as well as election returns. Is it doing so with Hobby Lobby?

Social and cultural tides ebb and flow. The new morality of the 1960s affirmed an exuberant sexuality facilitated by freedom from pregnancy. Feminist aspirations for equality in the professions rested heavily on avoidance of the burdens of child-bearing. In general, society was accommodative to the skilled and affluent, less so to those on the margins, for whom sexual freedom was more likely to result in child-bearing, social disorganization, and poverty.

Rapid social change is inherently disruptive and certain to generate opposition. Much of the political history of the last third of the 20th century and the early years of the 21st has been a reaction to a revolution in moral norms facilitated, but not caused, by easy access to contraception. The liberal reaction has been to ameliorate the hardships of the poor with scant attention to sexual behavior, the conservative reaction to attempt a recovery of older values. The nation appears deeply divided, and it is not clear that either impulse can prevail. The contraception mandate in the Affordable Care Act and the reaction against it is one manifestation of this division.

It is instructive that the Court’s five-justice majority consisted entirely of males who are practicing Catholics. Its four-justice minority included its three female members. Hobby Lobby is a skirmish in a cultural conflict likely to divide us far into the foreseeable future while relegating what remains of the economic divisions of the mid-20th century to a sideshow.

Alonzo L. Hamby is distinguished professor of history emeritus at Ohio University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.