In the early-morning hours of May 2, 2017, the base of the gilded statue of Joan of Arc in the French Quarter of New Orleans was tagged with the phrase “Tear it down.” This tag appeared in the midst of the removal of the city’s Confederate monuments. The week before, the first of four monuments was taken down amid a heavy police presence. Later in May, a statue of Robert E. Lee was removed from atop a 60-foot column. But how did the statue of a medieval female warrior saint get caught up in the controversy over Confederate monuments?

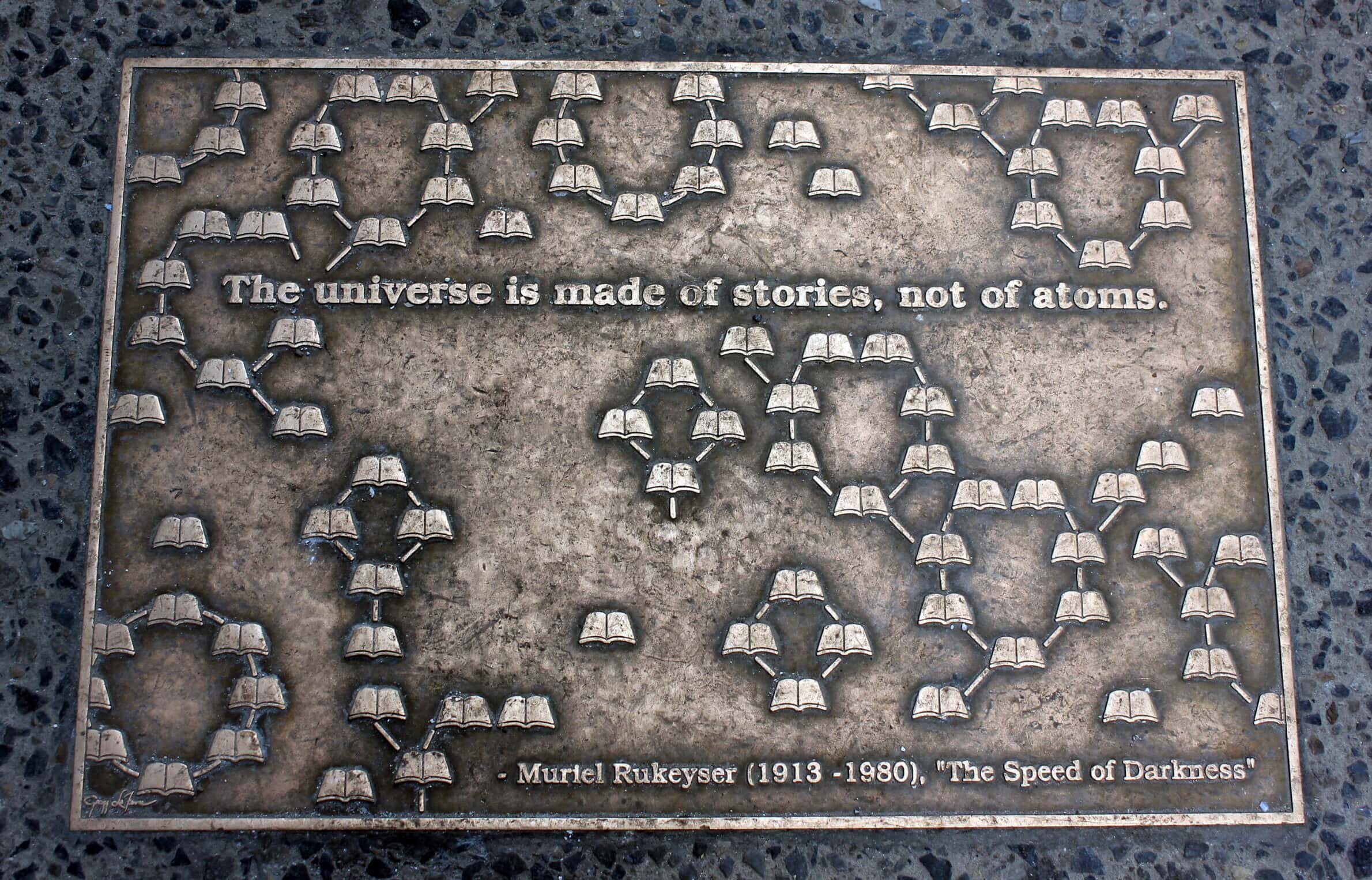

A stained-glass window in the University of Alabama’s W. S. Hoole Special Collections Library encapsulates the kind of medievalism prevalent in the American South. Zachary Riggins, University of Alabama

Among New Orleanians, the 15th-century saint Joan of Arc is known mostly for the Krewe de Jeanne d’Arc. This Mardi Gras walking parade kicks off Carnival season each year on January 6 and stops at the statue to pay homage to its namesake. In an interview with the Times-Picayune, the krewe’s founder, Amy Kirk Duvoisin, also expressed confusion about why Joan was targeted: “Surely, people realize she’s not related to American history.”

The vandalism of the statue of a medieval saint in the midst of local controversy over monuments and memorialization may have been a simple case of mistaken identity. However, the unknown tagger wasn’t wrong to associate a monument of a medieval figure with monuments of Confederates. Joan of Arc herself was appropriated by the women’s order of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s as an example that white women should emulate. Ideas about the glory of the Middle Ages have been used by white supremacists in the United States and Europe to reduce the real and complex history of that period to one focused on the supposed “white” origins of civilization.

History as a discipline, not just medieval history, has a race problem; history degrees earned at all levels are dominated by white people. Some of my students come to courses on the Middle Ages seeking stories of white heritage or exceptionalism, a narrative they might have learned from conceptions of the period here in the South and in popular culture more broadly. However, scholars and teachers of the period today are attuned to the role that race and racism plays in minimizing the reality of the global nature of the Middle Ages. Students encountering medieval views of the nature of just war, the treatment of women and minorities, or the development of good government see that they were rather different from modern views of these topics—and, sometimes, not different enough.

Our understanding of the past, our historical consciousness, is always shaped by how it was taught to us. As a medieval historian teaching in Mississippi and living in New Orleans, I am confronted every day with both the complexities of the region I live in and the period I study. Teaching the Middle Ages in the modern southern United States allows me to facilitate conversations with both students and the wider public that ask them to reexamine their ideas about the past in light of cutting-edge scholarship to shake off antiquated ideas that reflect neither historical realities nor who we are now in the 21st century.

I am confronted every day with both the complexities of the region I live in and the period I study.

In my experience, today’s southern students are up to the task. When given the choice between bromides about Whiggish progress or fantasy narratives of racial origins and the surprising and uncomfortable medieval primary sources, my students have mostly chosen the messy process of grappling with both lived experiences of the people of the past and literary representations of the Middle Ages.

Faux-medieval culture is everywhere. Medieval historians call this practice medievalism because it doesn’t actually refer to a real time or place in history. It’s about fantasies, most of them set in an imaginary past that bears little resemblance to the real one. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Romantic movement was Middle Ages obsessed, creating the equivalent of medieval fanfic poetry and art. This inspiration was particularly popular in Germany and England, evident in Richard Wagner’s 1857 Ring cycle opera (in which the Viking horned helmets were invented) and how Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his fellow Pre-Raphaelite artists mined Arthurian literature for inspiration.

It sounds innocent—plenty of people today enjoy a so-bad-it’s-good medieval fantasy film. However, the nationalist and colonialist impulses of the 18th and 19th centuries were partly expressed by seeking their “racial origins” in the Middle Ages. Eugenicists used these false ideas about the Middle Ages as a template for new national identities founded on the oppression and extermination of minority groups in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Looking back to an imaginary time of long-lost racial purity, white nationalists in the United States and Europe, be they Far Right politicians or soccer hooligans, want to claim that their countries “belong” somehow to white people. But as recent research in medieval archaeology has shown, people of many ethnicities lived across Europe in the premodern period. To see the dangers of this white supremacist ideology, one need look no further than the attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. Even today, white ethnic nationalism echoes with these medievalist fantasies.

Such medievalism appears in unique ways in the US South. Many plantation tours still talk about the chivalric masculine ideals of white southern slaveholders. The patriarchal southern elites imagined parallels between themselves and the feudal lords of the Middle Ages, though feudalism as a model for medieval political culture has been successfully dismantled by scholars.

One of the founding myths of the Ku Klux Klan from Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (1905) depicts the white-hooded costumes of these racial terrorists as akin to the “Knights of the Middle Ages [riding] on their Holy Crusades.” It is no accident that the post-Reconstruction racial terror campaigns in the South and the veneration of the Lost Cause used popular ideas and images from the literary medievalism of the period. Even contemporaries noticed the connection between these ideologies. In Life on the Mississippi (1883), Mark Twain observed with his usual irony that Sir Walter Scott and his medieval-themed novels, such as Ivanhoe (1819), “had so large a hand in making Southern character, as it existed before the war, that he is in great measure responsible for the war.”

The study of the medieval period asks students to grapple with beliefs that today would be considered racist or classist.

A stained-glass window, commissioned from Tiffany Studios by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1925, is still installed in the University of Alabama’s W. S. Hoole Special Collections Library. It depicts a white southerner as a medieval knight, surrounded by roundels with the official flag of the Confederate States of America, the Confederate battle flag, the flag of Alabama (adopted in 1895 and meant to echo the Confederate battle flag), and a white cotton boll. The inscription reads, “As crusaders of old they fought their heritage to save.” This view of the Middle Ages is pure white supremacist fantasy, a legacy not of the real people of medieval societies but of our own modern world.

The study of history asks students to step outside their own worldviews to another time and culture. While many fields of history have white supremacists trying to tell stories that are racist, it is particularly visible in medieval history. The problem isn’t fantasizing about the Middle Ages; the problem is when people think the fantasy is real. The study of the medieval period asks students to grapple with beliefs that today would be considered racist or classist, even barbaric. It is the job of medieval historians, who both research and teach on this subject, to make the Middle Ages accessible and relevant but also to contradict false and simplistic narratives about the past.

Just as antebellum elite white southerners imagined themselves as knights, not as peasants, when modern students imagine themselves in the past, it is usually as the elite, rarely the oppressed. In my experience, one antidote to this tendency can be the use of the historical role-playing game Reacting to the Past. In my courses, we have played several games, including Vikings Raid Iona!, created by Mary Valante and Vicky McAlister. In this simulation, students do not just role-play elite warrior culture but also explore other medieval identities, including enslaved people, women, and religious minorities. Instead of confirming their previously held ideas about the glory of a medieval fantasy world, games like these can push students out of their comfort zones in productive ways that engage their analytical skills and their historical empathy.

Like the Middle Ages, the early 21st century has been indelibly marked by crises, including global pandemics, popular revolts and uprisings, and climate change. Most recently, Hurricane Ida wreaked destruction on the city of New Orleans, site of the 2022 AHA annual meeting. The presenters in three linked sessions at the annual meeting, “Medieval Perspectives on Modern Crises,” confront the way modern crises of all kinds have made the Middle Ages seem shockingly relevant for students and teachers today.

Courtney Luckhardt is associate professor at the University of Southern Mississippi. She tweets @CLuckhardt.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.