Editor’s note: This is the first installment of a two-part column. The second installment can be found here.

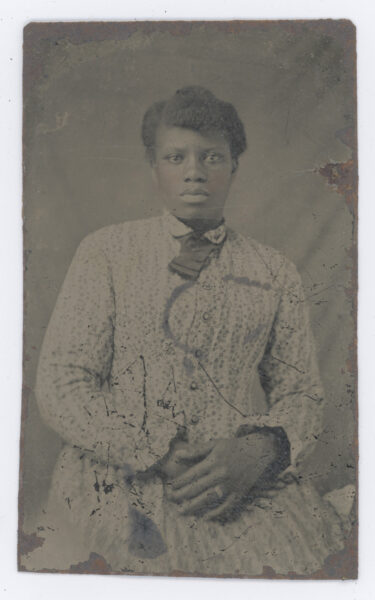

The sitter faced the camera directly, locking eyes with her viewer. Her hair was pinned back in three sections. Her hands were crossed on her lap, left over right, revealing a ring on her left ring finger. Her dress featured a fitted bodice fastened with contrasting-colored buttons, light circles inscribed in alternating dark and light rings. The cloth was a simple star pattern. Color had been added to her cheeks, giving them a rosy hue and adding liveliness to her face.

Researching 19th-century photographs like this were an entry point into digital projects for . Courtesy The Baltimore Collection, University of Delaware Library, Newark, Delaware

This is one of 53 photographs from The Baltimore Collection, produced between 1850 and 1950. This collection at the University of Delaware predominantly features black sitters in photographs from Washington, DC; Philadelphia, PA; and its namesake, Baltimore, MD. The sitters, including this woman, are mostly unidentified. I spent months researching this photograph and others in the collection. Conducting this research served as my first introduction to digital history as a means to contribute to the field of history.

I joined the digital history project working with The Baltimore Collection as a student in the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture. In the fall of 2017, I also began working with the Colored Conventions Project, which digitizes documents detailing political conventions organized by African Americans from 1830 to the 1890s; it captures the measures that members of the free black community took to collectively fight for their rights as American citizens. These two experiences taught me how to apply my skills as a historian in a team setting, creating new knowledge about previously unknown sources and making these insights available to the public.

Using digital history as a pedagogical tool engages students like me in conversations about history and how it can be preserved. It opens our eyes to every step of the knowledge production process, reinforcing the significance of our work as historians. Digital projects like these encourage us to reflect not only on what we are learning, but also why we are doing the work and what skills we build in the process. Whether using digital history as a self-contained classroom tool or developing an ongoing initiative, a few key practices will help strengthen digital history projects and sustain student engagement throughout the life of the project.

Digital projects like these encourage us to reflect not only on what we are learning, but also why we are doing the work and what skills we build in the process.

Unity of purpose is vital to any successful digital history project. The students I worked with on these projects shared a passion for history and an interest in archives. We all believed in the importance of investing in, celebrating, and elevating under-researched historical experiences through archival preservation. Collaborating around a common goal made us a team. Further, working on a single collection made it easier for students to support one another across projects. Whether conducting contextual research, building the website, or formatting metadata, we were all able to come together to talk about the triumphs and struggles of building our project.

In designing digital history projects, it is essential that project leaders incorporate student voices from the beginning. Decide on a target audience together. The Baltimore Collection and the Colored Conventions Project identified the same group as their target audience—academics. Built by academics for academics, these projects focused on connecting scholars to new resources about African American history. Focusing on a specific audience gave us clarity of message, continuity of writing style, and a clear vision of what elements needed to be included and what preexisting knowledge our audience would already bring to the table.

Digital projects are also an opportunity to introduce students to a network of professionals who are engaging in similar work. In a classroom setting, guest speakers can share their experiences and provide advice on the project. Students on The Baltimore Collection and the Colored Conventions Project met frequently with professors, archivists, librarians, and community members. Creating a space of intellectual exchange introduces students to a network in which they can continue to participate long after the class ends or the digital history project is finished.

In designing digital history projects, it is essential that project leaders incorporate student voices from the beginning.

Along with a professional network, students will come away from these projects with new skills. Transparency about the skills used in digital history projects lets students draw connections between their work as researchers and teachers and the work of public historians. For example, navigating archives is at the center of what historians do. Digital history projects are a way to teach students how archival collections are started, developed, categorized, and organized, giving students a better understanding of what went into the collections in their research.

But not all skills will be new; digital history projects offer students an opportunity to contribute skills that they already have to the project. They may bring experience in web design, blogging, social media, curriculum development, archival work, or photo editing—all skills important to the development and execution of a digital history project. In the Colored Conventions Project, graduate student leaders created, planned, and implemented new initiatives and programs in public engagement and metadata and curricula development. With The Baltimore Collection, I used previous WordPress experience to help develop the website. Both projects gave students opportunities to advance the overall goals of the group through their preexisting skills while developing others along the way.

Finally, students can act as public ambassadors for the project throughout its lifetime. I spoke at the 2020 AHA annual meeting about The Baltimore Collection and its importance to studies of black life in the 19th century. Graduate students regularly speak at national conferences about the Colored Conventions Project. The Colored Conventions Project also hosts webinars for the public, collaborating with institutions such as the Smithsonian to reach a broader audience. Student-driven enthusiasm pushes the project and its audience to continue to grow over time.

Digital history projects serve as a crucial training ground for graduate and undergraduate students. It also gives students another space in which to develop their skills in communication, writing, and project management. My time conducting metadata research for these projects, such as the photo of the unidentified woman, inspired me to pay it forward and bring these skill-building opportunities to my own classroom.

Allison Robinson is a PhD candidate in American history at the University of Chicago. Her dissertation examines race making and the legacy of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the Works Progress Administration. Allison holds a BA in history from Yale University, an MA in history from the University of Chicago, and an MA from the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture at the University of Delaware.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.