In August 2022, I began designing my first course at People’s Preparatory Charter School in Newark, New Jersey. During my teacher training, mentors like Tracy Pelkowski emphasized the importance of culturally responsive teaching. Yet I was still unprepared for the experience of starting my first teaching role in New Jersey’s largest and most diverse city. As a dual-enrollment class in collaboration with Kean University, the History of the Holocaust and Genocide Studies course was for juniors and seniors. I anticipated that my students would have limited knowledge of Jewish culture and history—a largely accurate prediction. As I recognized that, for many of them, I might be their only source of education on the Holocaust, my initial feelings of fear and uncertainty gave way to determination and resilience.

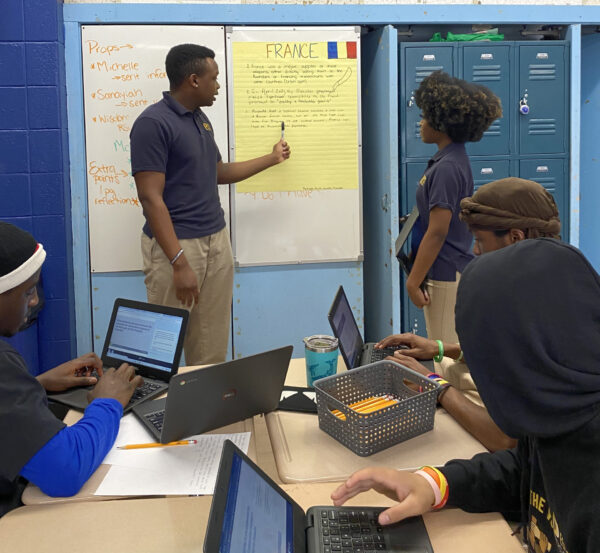

Students in Kyra Dezjot’s course History of the Holocaust and Genocide Studies teach each other about the history of Rwanda. Kyra Dezjot

I reviewed the New Jersey Student Learning Standards to design my course using a backward-design approach (i.e., standards, objectives, assessments, and instruction). When I first read the standards for social studies, I was pleased, as a Jewish teacher and a historian of Jewish life, to find the inclusion of the history of the Holocaust and genocide. New Jersey had a seemingly robust mandate for Holocaust education and even had a law requiring Holocaust education in all schools. New Jersey is not alone in these requirements: According to the AHA’s 2024 report American Lesson Plan, 29 US states require or promote Holocaust and genocide history in their state standards or laws governing K–12 education. Given New Jersey’s prominent Jewish population and several universities’ Holocaust resource centers, the presence of a Holocaust mandate did not surprise me. Still, I felt reassured that the New Jersey Student Learning Standards backed the Holocaust curriculum I planned to teach.

But though relieved that the standards aligned with my course objectives, I nonetheless was concerned that all my students would learn about Jewish people was the Holocaust. The standards focus entirely on genocide, the international response to genocide, and citizens’ responsibility to fight oppression. If I stuck only to these requirements, students would not learn about the prosperous Jewish communities in eastern Europe before World War II; Jewish inventors, scholars, and politicians; or anything about Jews outside Europe.

This is perhaps unsurprising. When teaching the experiences of minority groups—including Indigenous peoples, African Americans, and Jews, among others—state standards tend to focus on teaching what journalist Lucy Dawidowicz called “oppression studies.” In the case of Jewish identity, the discussion in most classrooms begins and ends with the Holocaust. With their stories starting in the 1930s and ending in the 1940s, Jews are often presented as victims of Nazi fascism rather than as individuals with whole lives. But I didn’t want the only Jewish history I taught to be about genocide and oppression. I realized I needed to expand the history of Jewish experience in my classroom—even if it meant going beyond the New Jersey standards.

I was concerned that all my students would learn about Jewish people was the Holocaust.

I decided that a research-based approach would allow me to include a more holistic view of Jewish life. Therefore, I decided to approach Holocaust studies from a person-centered lens. A person-centered lens stems from sociological modules, where some seek to see people beyond their illness or disabilities. In an education context, the University of Minnesota Center for Practice Transformation defines the goal of person-centered language as “respecting the dignity, worth, unique qualities and strengths of every individual. A person’s identity and self-image are closely linked to the words used to describe them.” I decided to take this framework and apply it to history education, going beyond a one-dimensional portrayal of Jews and other minorities as victims and focusing on other aspects of their lives to convey a three-dimensional account of their histories.

My course began with the Armenian genocide and Jewish life before World War I. After learning about the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, students jumped into independent research, during which they investigated the Armenian genocide using primary and secondary sources. We read Ravished Armenia, Aurora Mardiganian’s firsthand account, and The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America’s Response by Peter Balakian, whose ancestors survived the genocide. In addition to reading, we watched clips from Ararat, a fictional film commemorating the Armenian genocide. Students presented their findings on diverse aspects of the Armenian genocide by creating posters and presentations. On presentation day, the classroom felt transformed into a museum exhibit, with students (now experts in their specific topics) presenting on different aspects of the Armenian experience. Shifting into the teacher position early in the course, students were prepared and able to engage in independent research about the Holocaust.

We began our Holocaust unit in the 19th century, leaning heavily on resources from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Yad Vashem, and Hidden Voices. A project produced by the New York City Public Schools, Hidden Voices aims to “help City students learn about the countless individuals who are often ‘hidden’ from traditional historical records,” including Jewish narratives beyond the Holocaust. These resources often focus on the intersection of Jewish life with other minority groups, citing Jewish American activists in the LGBTQ+ and civil rights movements. By encountering Hidden Voices stories before instruction on the Holocaust, students learned a framework of aspects of Jewish life I had never learned when I was their age. For example, we studied the cultural aspects and importance of the Yiddish language and the creation of Jewish communities in Poland, Russia, and Germany. We also looked at the accounts of Jewish immigrants to America during the interwar period to draw a connection to the Jewish community in the United States. Once students understood that Jews existed in prosperous communities before 1923, then I was ready to teach the history of antisemitism and the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party.

Throughout the unit, I incorporated performance-based assessments and shifted the focus to students in the classroom, asking them to teach me about the Holocaust using assigned sources. For example, students completed a project where they researched victims of the Holocaust other than Jews. Students researched their group—for example, the Roma people or LGBTQ+ individuals—and then taught the class using materials, a presentation, and a lecture they created.

By engaging with the Holocaust from various lenses, students learned that Jews and other victims were not only oppressed people in Nazi Germany. Instead, oppression was just one element of their complex identities. These individuals were also mothers, fathers, children, politicians, religious leaders, store owners, and so much more. By learning a complex background history of Jewish life, students saw Jews beyond victimhood. By expanding their knowledge of the Holocaust to non-Jewish victims, they also came away with a more complex understanding of these atrocities.

Oppression was just one element of Holocaust victims’ complex identities.

I continued this strategy in our unit on the Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda. We looked at the demographic makeup of Rwanda from the 18th century to the 1990s, explored the education system in Rwanda, and learned about Rwanda’s four national languages: Kinyarwanda, French, English, and Swahili. This interested my students since some were Swahili or French speakers and some shared comparisons between their home countries and Rwanda’s history. After exploring Rwanda and its ethnic groups, the Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa, we focused on the events of 1994. Given the recentness of the genocide’s events, I was able to use an incredible number of online primary sources translated into English. Using IWitness from the USC Shoah Foundation, students explored the testimonies of victims, perpetrators, and bystanders. By hearing the testimonies of both perpetrators and victims, students grappled with the responsibility of European colonial powers for the genocide. Students left this unit demonstrating a rich understanding of victimhood and responsibility in their summative assessment essay on responsibility for the genocide.

In the last section of the course, we studied a contemporary and controversial “genocide.” In the first year I taught this course, we discussed the experiences of Uyghur Muslims in China. In 2024, we studied the complex history of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, focusing on media literacy.

The results were the same in each of the class’s four units. Regardless of the group being studied, purposefully teaching their rich history led students to understand these people as not simply victims. Students used person-centered language to discuss the experiences of oppressed peoples, and they came away with a deeper understanding of cultures and experiences before tragic events affected these communities. Although state standards do not outline how teachers can be more inclusive when teaching about the Holocaust and genocide studies, if teachers work together and use the many available resources, they can empower their students to deepen their historical understandings using a person-centered mindset.

Kyra Dezjot is a former high school teacher and a history doctoral student at Fordham University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.