Editor’s Note: This is the third of three articles reporting findings from the spring 2010 survey of research and teaching practices (previous articles appeared in the October and November issues of Perspectives on History). Discussion of these findings will be part of the session “What’s Next? Patterns and Practices in History in Print and Online,” scheduled for Saturday afternoon at the January 2011 annual meeting.

The AHA’s spring 2010 survey of academic historians showed careful adoption of new media into their research and writing practices, but evidence for their adoption of digital technologies into their history classrooms was comparatively mixed, especially as indicated by the responses to a set of open-ended questions on this subject. Unlike the questions about use of media for scholarship, questions about technology use for teaching elicited much more passionate (and often negative) responses.

Some Data about Types of Courses Taught

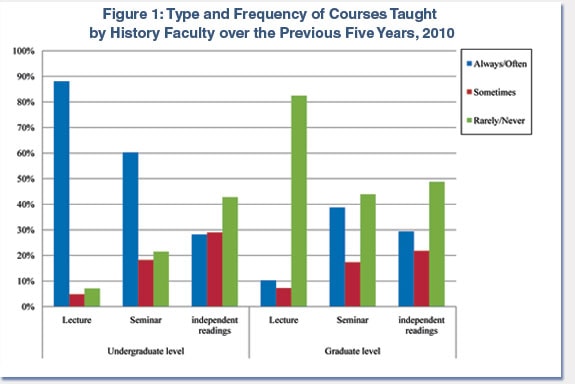

To establish a baseline for identifying a faculty member’s knowledge about teaching practices in different course types at the undergraduate and graduate level, the survey asked faculty how frequently they taught particular kinds of classes over the past five years.

Almost all of the respondents reported regularly teaching undergraduate lecture courses during the period in question, and 60 percent of them regularly taught undergraduate seminar courses as well (Figure 1).1

Surprisingly, there was relatively little variation across the different institution types, and senior faculty reported that they always or often teach undergraduate lecture courses at almost the same rate as junior faculty—86 percent among full professors as compared 92 percent among assistant professors. Note, however, that the survey only asked about how often they taught a particular type of course—not the quantity taught in any given year. That could mean that a senior faculty member “always” teaches one undergraduate course per year while a junior faculty member regularly teaches three or more in the same department.

The survey responses show that relatively few faculty used the lecture method at the graduate level, as fewer than 10 percent of the respondents (13.5 percent of the faculty at programs conferring graduate degrees) reported that they regularly teach graduate lectures. Faculty at programs that confer the master’s as their highest degree (typically at comprehensive public universities) were the most likely to use lectures for some of their graduate courses.

The seminar course clearly remains the preferred method for graduate study, as 37.7 percent of the faculty at programs conferring graduate degrees regularly teach graduate seminars. Not surprisingly, 59.8 percent of those who actually teach some graduate-level courses use the seminar method. The survey found very little difference in the proportion of faculty regularly teaching seminar courses at master’s and doctoral level programs. Respondents at doctoral programs were slightly more likely to report regularly leading independent readings at the graduate level, as 42.2 percent of the faculty at doctoral programs said they did so as compared to 36.8 percent of the faculty at master’s-level programs.

Technologies in the History Classroom

The wide and diverse array of courses represented by the respondents offers a solid foundation for assessing the penetration of technology into the history classroom. The most striking feature of the responses to this set of questions in the survey was the substantial number of objections voiced about new media use in this area of history work.

Twice as many respondents offered detailed concerns about the use of new media in the classroom as compared to a similar question about the use of technology for research and writing (489 respondents, as compared to 208).

Some of the faculty expressing concerns did so from the position that they failed to see the ways in which technology could improve upon or assist the traditional methods of pedagogy. Echoing the comments of many others, one respondent observed that, “Technology isn’t everything and I’m not convinced that all the bells and whistles work measurably better than a strong lecture or discussion”. And a few cited personal experience as validating that view. One noted that, “I have used it long enough to observe that students don’t benefit from the use of many types of technology.”

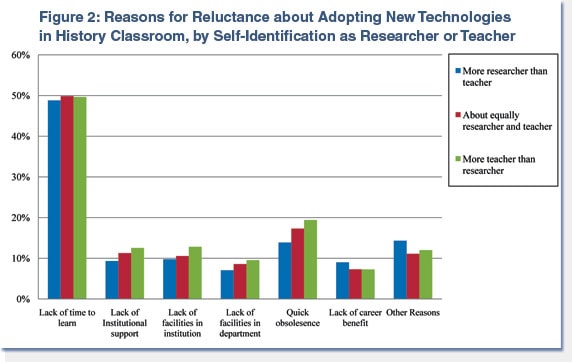

Among the choices offered in the survey as causes for reluctance about new technologies, almost half of the respondents cited conflicting pressures of time and other commitments. But faculty members who consider themselves more teachers than researchers were the most likely to express a wider array of concerns—particularly about the swift obsolescence of digital technologies and the lack of institutional support and facilities (Figure 2).

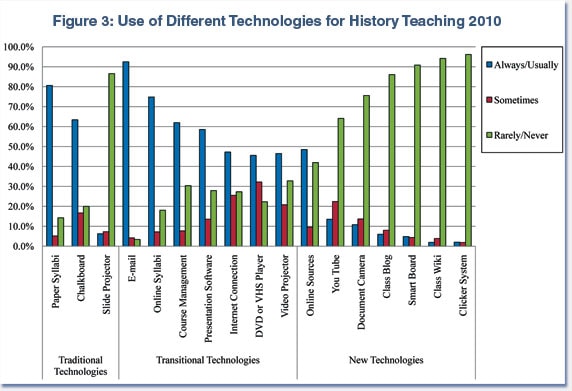

Given these general concerns about the use of new media for teaching, it is hardly surprising that the survey showed fairly limited use of different media in and for history teaching. The traditional elements of history courses persist in many history classrooms, as paper syllabi are always or often used by 81 percent of the respondents and chalkboards were regularly used by 63 percent (Figure 3).

Despite the widespread use of paper syllabi, 75 percent of the respondents said they also make their syllabi available online. And even though anecdotal evidence suggests many students consider it passé, 92 percent of the respondents reported making regular use of e-mail in their instructional work.

Course management software was reportedly used by 62 percent of the history faculty in the survey, but these programs were singled out for particular scorn by a number of faculty, both for their clunky interfaces, and frequent upgrades that impose additional burdens in time, effort, and expense. As one respondent observed, “When institutions subscribe to software for teaching such as Blackboard, the software updates often force premature obsolescence on the hardware. The institution and the individual faculty members must either replace costly equipment more often than necessary (with additional costs to the environment), or struggle along with slow hardware. The software “updates” are usually unwieldy, with few real improvements (and often setbacks). They waste valuable faculty time. Such trends should be examined and monitored carefully by the profession.”

Over half of the respondents (and 92.1 percent of the faculty who regularly teach undergraduate lecture courses) said they always or usually incorporate presentation software such as PowerPoint into their courses. But here again, the lack of adequately maintained facilities for the use of presentation software was often singled out as a problem by respondents. One faculty member observed, “Usually, you have to have two to three backup plans when using technology, due to the constant problems. When presenting PowerPoint, I always have a paper copy so if the computer doesn’t work I can put the slides on the overhead; if the overhead doesn’t work I can hold them up and walk around the room.” Those comments were echoed by more than a dozen of the other respondents.

A significant number of the respondents (45.5 percent) also said they regularly use videos (on DVD or tape) in their courses. The level of use was slightly higher among faculty who taught undergraduate and graduate seminars than among faculty who teach lecture courses, but here again, the problem of technology breaking down at crucial moments during a class was a recurring concern.

In comparison to technologies that have been in fairly wide use for a decade or more, newer technologies receive relatively little use in history classes. Fewer than half of the respondents said they regularly use online sources as part of their courses. (Respondents were not asked to assess the extent of use by their students, whether with or without their encouragement.) YouTube was reported as used by 14 percent of the respondents, while 11 percent of the respondents reported the use of scanners or cameras to prepare and provide source materials to their students.

Technologies to develop interaction among students in cyberspace were rarely used by faculty who responded to the survey. Six percent of the respondents reported the regular use of class blogs, and 1.9 percent reported the use of wikis in their classes.

Similarly, only 4.9 percent of the responding faculty said they regularly used electronic “smart boards,” while 2 percent of the respondents said they used clicker systems. A number of the respondents expressed interest in these technologies, but noted that their department rarely had access to rooms with those technologies, making it risky to prepare courses around their use. As one respondent noted, “[m]y institution has facilities but in history classrooms they are unreliable and poorly staffed.”

A few respondents noted that they were under some pressure from their institutions to adopt technologies like clicker systems, but objected to them on pedagogical grounds. One respondent observed that, “Things like clickers, which my university appears to be trying to promote, project the entirely false idea that history is something that lends itself to two-second evaluation and yes-no answers.”

Surprisingly, there was relatively little difference in the use of technology among those classified as power users and active users based on their adoption and use of new media for their writing and research. While the “power users” were generally less likely to use chalkboard and paper syllabi than those identified as active users in favor of their digital counterparts, they used media such as videos and presentation technology at about the same rate. The one significant difference was in the use of class blogs—which were deployed by 21 percent of the power users as compared to 6 percent of the active users (and 0 percent of the “avoiders”).

Based on the responses to the survey, the substantial gap between attitudes and expectations about technology for research as compared to teaching seem based on a number of issues that merit further study. Adoption of new media for research and writing clearly follows the respondents’ ability to identify clear benefits for their work and control many of the technological variables (such as choices of software and when and how to upgrade them). The use of technology in the classroom appears hampered by a lack of perceived pedagogical benefits in many technologies, exacerbated by steeper learning curves and inadequate institutional support.

Note

- Only 4,014 of the 4,182 respondents to the survey indicated that they actually had taught a course, since the respondents included a number of senior and research faculty who had not taught a course over that span. [↩]