“The Administration of Serendipity.” When I saw the title of the lecture in November 2013, I knew it would be a great one. Joachim Nettelbeck, the legendary founding secretary-general of the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin/Institute of Advanced Study, had agreed to present an outline of how to run a research institute. Nettelbeck believed that good administration meant working to create the seemingly spontaneous conditions for intellectual combustion. In a way, he was suggesting that, like the Renaissance courtier, the ideal administrator possessed a kind of sprezzatura, making complicated, long-planned maneuvers—or complicated meetings—look simple and effortless.

Of course, you might say, the director of a research institute has an impact on research. But the “serendipity” extends much further. The fact is that all academic administrators can and do shape fields of scholarship by way of appointments, budget allocation, programming, and just plain keeping a thumb on the scale. Sometimes—and maybe even most of the time—there may be little in these micro-decisions beyond local, even venal, necessity. But that does not mean that administration cannot have in it a set of intellectual ambitions.

So here is the main point: with all the different kinds of history we practice, there is still no intellectual history of academic administration—no awareness that administrators might intend their actions as argument by other means, might see their work as creating not just discrete possibilities for others’ inquiries, but whole fields of inquiry.

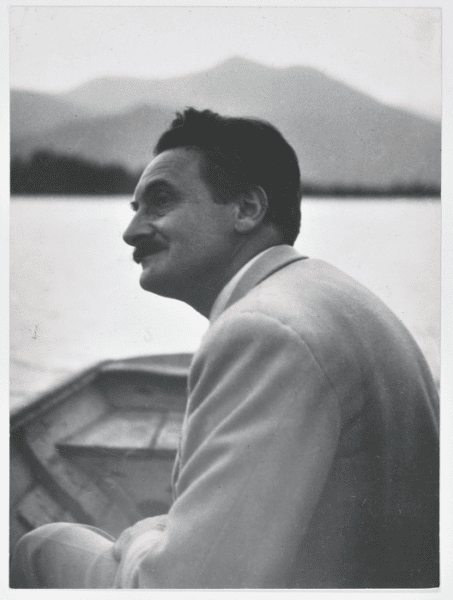

Fritz Saxl played a critical role in protecting the Warburg Institute from the Nazis. Courtesy of the Warburg Institute

For example, Fritz Saxl is well known today as an art historian and a leading figure in the circle of Aby Warburg, which also included the art historian Erwin Panofsky and the philosopher Ernst Cassirer. His erudition is awesome and his essays whirlwind tours of iconographic dexterity.1 Saxl was also the second director of the Warburg Institute, and, with Gertrud Bing, he masterminded the rescue of the institute and its library from the Nazis in 1933. But only those who have themselves done research on Warburg know also that in the 1920s, while Warburg was being treated in a sanatorium, Saxl ran the institute (known then as the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg) in Hamburg. As the acting director, it was Saxl who initiated the series of evening lectures and the publications, both the yearbook and the book series, that created a public for the innovative scholarship associated with Warburg and his circle and laid the foundation for the future. (Of course, Warburg himself, when he returned as director, played a central role in the design of the library’s new building and in the development of new technologies of teaching and display, among other details of technical administration.)

Saxl was a great scholar. What little we know of him as an administrator derives mostly from his fame as a professor and his proximity to Warburg. Clemens Heller, however, was not a great scholar, though he did have a PhD in economic history. He made his career through a close working relationship with his good friend Fernand Braudel. From around 1950, when he arrived in Paris from Salzburg, he held various positions within the Sixth Section of the École Pratique des Hautes Études, particularly its Centre de Recherches Historiques. Heller was the École’s, and Braudel’s, diplomat-in-chief. It was Heller, for instance, who served as the principal liaison with the American foundations whose support helped Braudel turn the Sixth Section into the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and then gave it the particular form of the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme. He followed Braudel as its second president (1986–92).

An administrator without an academic’s knowledge, or an academic without an administrator’s ability to translate ideas into planning, funding, and implementation, could not have made all this happen.

This may sound like an administrative career, pure and simple, however dusted with genius it might have been. But Heller’s work as an administrator went much, much deeper into the world of ideas. We can catch a glimpse of this through the keyhole provided by the preservation of his personal papers, a large portion of which are organized by country. The different dossiers contain records of Heller’s academic diplomacy around the world. The folder marked “Israel,” for instance, contains the letters Heller exchanged with S. D. Goitein, the great scholar of the Cairo Geniza.2 But in 1954, when Heller sought out Goitein through the mail, the latter had written just one article on the merchants of medieval India whose letters were found in the Geniza. Heller read the article and immediately wrote to him, offering to publish it in one of the book series that his friend Braudel directed through the Centre de Recherches Historiques. For the next decade, Heller engaged Goitein in a series of discussions about the scope of his project, its articulation, and its best form. Without Heller, there would have been noMediterranean Society, Goitein’s five-volume magnum opus, even if this was not exactly Heller’s preferred outcome. But the point is that an administrator without an academic’s knowledge, or an academic without an administrator’s ability to translate ideas into planning, funding, and implementation, could not have made all this happen.

The Heller archive also sheds light on Braudel, particularly on his work as an administrator—an aspect of his career that has gotten virtually no attention. Here, the question is necessarily somewhat different: how might what we learn about Braudel the administrator change what we think of Braudel the historian? The answer, I think, is significant. The Braudel of the two great multivolume works The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II and Civilization and Capitalism 15th–18th Century is a historian of the macro scale. At the level of the sound bite, the takeaway is his word picture of the lives of men as equivalent to the froth on the waves of the ever-rolling, ever-shifting sea. But the Braudel of the Heller papers doesn’t just act like someone who believed that individuals can make history; he actually supported intellectual projects that made this argument. The two book series he directed—in which, for example, Heller proposed Goitein publish his Geniza work—were devoted to individual lives on a day-to-day basis.

So why do we know so little about the work of people like Heller? Why do we not study the intellectual history of academic administration? Part of the answer is surely structural. Like doing the cultural history of the material world, an intellectual history of an institutional structure crosses one of the fundamental fault lines of academic history. On one side lie studies that focus on individuals and their thoughts and actions. On the other lie works that bring attention to impersonal structures and slowly moving collectivities. Then there is the university’s own emphasis on “pure” or disciplinary knowledge, rather than “applied” learning. Administration is nothing but applied learning.

There is also a personal element. Many professors seem to show a sniffiness toward administration and administrators. It’s simply not seen as an intellectual operation—few would compare being a dean to, say, being an astronomer or even a clinical psychologist—and those who do it are often seen as inferior to those who remain in full-time teaching and research positions. In the deep, dark collective psyche of universities, administrators have ceased to be scholars, and scholarship is the coin of the realm. As to why the administrators don’t themselves write the history of academic administration, aside from the endemic shortage of time in the day—we can’t all be John Boyer, who wrote 16 monographs on the history of the college at the University of Chicago during his 20 years as dean, and just published a very long narrative history—there may even be a kind of bad conscience at work that prevents them from seeing the intellectual side of what many consider their day job.3

If all this is true, why imagine the possibility of a new focus of historical research? Well, for one thing, there’s always a need for new topics to feed the future. But much more importantly, we are living through a moment when not inter- but cross-disciplinarity seems to offer real possibilities. If the history department at Stanford University offers a joint program with computer science (to point to only the most extreme of these couplings), there’s no reason why intellectual history can’t link up with administrative history. Even more to the point, with all the pressure straining the link between higher education and the humanities, it’s hard to deny that what administrators do and say actually matters. As in all crises, people turn back to the past to understand how we got here and how we have managed similar crises. That the university has survived for 800 years—arguably the single most successful European institution—is testament to its ability to adapt to changing times.

But “universities” didn’t adapt: the people who ran them made decisions to shape and reshape curricula, which, at a distance in time, reads as adaptation. If an intellectual history of academic administration helps us understand 13th-century Oxford, 17th-century Padua, and 20th-century Paris, it may also be a useful tool for understanding the changing university of the 21st century.

Notes

1. A full bibliography can be accessed through the online catalog of the Warburg Institute,https://catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/search/?searchtype=a&searcharg=saxl+fritz&searchscope=12&SORT=A&Submit.x=0&Submit.y=0.

2. Studied in , “Two Men in a Boat: The Braudel-Goitein ‘Correspondence’ and the History of Thalassography,” The Sea: Thalassography and Historiography, ed. Miller (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 2013), 27–59; idem, “From Spain to India Becomes A Mediterranean Society: The Braudel-Goitein ‘Correspondence’ Part II,”Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 56 (2014): 112–35.

3. Boyer’s “Occasional Papers on Higher Education” can be found at https://college.uchicago.edu/about/publications; see also The University of Chicago: A History (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2015).

Peter N. Miller is dean of Bard Graduate Center in New York City.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.