From May 1775 to July 1776, representatives from 13 British colonies along the Atlantic in North America gathered in Philadelphia to discuss the escalating tensions with Britain. Over the yearlong hearings, these delegates debated the benefits of remaining part of the British Empire or forming a collection of independent states. This Second Continental Congress culminated with all 13 colonies signing the Declaration of Independence.

Richard H. Tomczak holds the Olive Branch Petition to King George III, April 1, 2024, Signed by Delegates Representing All Thirteen Colonies Having Met and Convened at Stony Brook. Richard H. Tomczak

This spring, I piloted a 10-week seminar at Stony Brook University for first-year students based on these events. Students were divided into 13 groups and assigned a colony. For the first half of the course, the five students in each group researched their colony, and prepared a justification for signing the Declaration of Independence or a vote to reconcile with the king. In the remaining five weeks, a mock Congress simulated the touchpoints of the historical gathering of delegates, including speeches and voting on policies. The course generated considerable enthusiasm among the students. Passionate speeches for and against independence incited real debates over the fundamental roles of government and the importance of trade in the 18th century.

With this course, I aimed to reach a deeper understanding of the entangled relationships among history, active learning, and project-based assignments. Humanities faculty who engage in active learning projects report increased participation in class, development of research skills, and creative approaches to problem solving. This is especially true in history classrooms that include project-based assignments that build, and reinforce, skill sets needed for the 21st-century workforce.

Importantly, our mock Congress occurred as a collaboration with Stony Brook’s Educational Opportunity Program (EOP). These programs are designed to fulfill New York state’s commitment to providing access to higher education for economically disadvantaged students who possess the potential to succeed but whose academic preparation in high school may not fully prepare them to pursue college education successfully. This diverse group may enter Stony Brook without the benefit of Advanced Placement credits and additional co-curricular engagement often available to students from more privileged schools. As a result, this seminar potentially provided some students with their first opportunity to build research self-efficacy as they articulated their argument for or against independence. In addition, undergraduates from high-needs school districts often are not sufficiently exposed to the complexities of the humanities and social sciences, resulting in a lack of diverse students’ interest in these areas. I designed this seminar as a high-impact opportunity, instilling persistence and bolstering research skills at a critical opening point in their education.

The lead-up to the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution provides new ways to recast the interpretation of that conflict. As historians highlight the diversity of voices that participated in that conflict, I learned that this seminar was not only an opportunity to simulate some components of the Second Continental Congress but to reinterpret them entirely. Put another way, I encouraged students to both reckon with the fraught history of inequality embedded in colonial institutions and to generate their own informed arguments.

This seminar was not only an opportunity to simulate some components of the Second Continental Congress but to reinterpret them entirely.

The course took place as part of a series of first-year seminars hosted by Stony Brook’s Undergraduate Colleges. Each group received a packet of secondary scholarship and primary documents specific to their assigned colony. In this portion of the course, they critiqued Enlightenment-era political theory, and I delivered strategic lectures dedicated to the enslaved Africans forcefully transported to the Americas and the impact of that labor regime on colonial governments. Such background knowledge was essential, because the plantation complex of the southern colonies underpinned many of the political decisions made by delegates from that region.

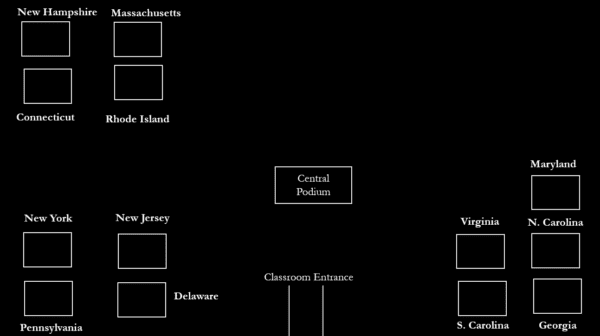

During this stage of the course, I organized the room to match the colonial geography. Taking place in Stony Brook’s large active learning classroom, students assigned to New England sat in the northwest corner of the room, the mid-Atlantic in the southwest, and the Chesapeake, Carolinas, and Georgia in the southeast corner. Groups representing New Hampshire and Georgia were in opposite corners of the room, thus reconstructing the distance of travel between colonies.

During the first five weeks, the classroom layout recreated the geography of the 13 Anglo-American colonies.

The remaining five weeks included a simulation of the Second Continental Congress. Students learned the historical context of the events that led to independence from Britain, deployed collaboration strategies as they worked within their groups, and developed public speaking skills to persuade other colonies to their side as they delivered speeches as congressional delegates. Periods of dissent focused on student-driven arguments related to allying with France for military support, finding new trading partners in the absence of the British, and the role of New England in instigating the broader conflict. New York, South Carolina, and Georgia all seriously cast doubt on the colonies’ economic posterity should they rebel.

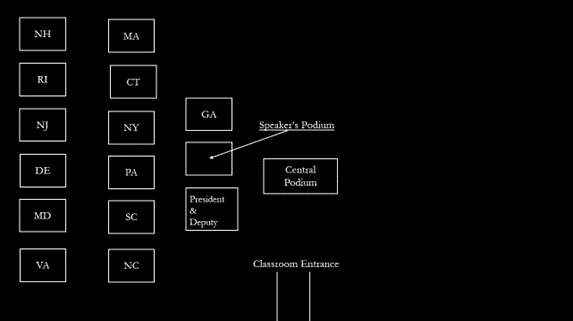

I encouraged historical immersion in a few ways. During our simulation, I acted as president of the Congress, calling the delegates to order with a gavel. I replaced the class syllabus with an “Order of Congress,” complete with formal decorum. I encouraged passion and enthusiasm around a particular argument, but it was equally important that such excitement should not come at the expense of the historical evidence. There was no toleration for name calling or jeering from the delegations, though students could knock on the table and yell “Hear, hear!” in agreement once speeches ended. The classroom layout changed during the simulation, shifting so the delegates met on one side of the room.

The classroom layout changed during the simulation of the Second Continental Congress, instead meeting on one side of the room.

While I encouraged historical debate, this was not a role-playing exercise. I made it very clear that they were 21st-century students analyzing primary documents and secondary scholarship to craft their own interpretation of the Congress. I specifically dissuaded them from taking on the role of the historical delegates, especially because many of these white affluent men owned enslaved individuals of African descent and had settled on land appropriated from Indigenous people.

I employed two strategies to navigate the structural inequality embedded in colonial institutions without diluting the reality of life in 18th-century British North America. First, we spent the opening weeks of class looking at readings that directly addressed these topics and I talked them through the intricacies of 18th-century labor in the Atlantic world. Second, I structured debates in the mock Congress around a much narrower discussion of sovereignty in the British Empire. Some students interpreted sovereignty as economic independence, and thus the commodities their colony produced did come up. This way, students learned of the inequality embedded in colonial institutions, but they did not need to defend or vilify it in their speeches. In sum, students grappled with the effects of colonization of Indigenous communities and enslaved Africans, but their debates had specific parameters, ensuring that no student felt uncomfortable with the source material.

The five-minute recess leading up to the final vote on the Declaration exploded in activity, as other delegates scrambled to convince South Carolina otherwise.

Our vote for independence replicated the conditions of the historic Congress. In 1776, 12 delegations approved the Lee Resolution, which stated “that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states.” The New York delegates abstained in order to return to their province and obtain further instructions. In our class, the first vote landed 12–1 for independence. Only South Carolina held onto reconciliation, skeptical of their economic future without being able to trade rice and indigo within the British Empire. The five-minute recess leading up to the final vote on the Declaration exploded in activity, as other colonies’ delegates scrambled to convince them otherwise. In the end, South Carolina’s economic arguments ultimately persuaded two other colonies to reconcile (New York and Georgia), and we signed our own version of the Olive Branch Petition.

In sum, what started as a historical exercise developed into a serious reinterpretation of the events by an underrepresented population of students. The debates produced very real disagreements over the foundational principles of the United States. It was—and professors don’t often admit this—difficult to manage, as I ceded much of the time to the students themselves. In a more traditional lecture-style classroom, students, especially EOP students, rarely have the opportunity to declare ownership over the course content and the very meanings of history. They had the chance to interpret a time period dominated by white men and archival documents that often silenced underrepresented voices. I encourage you to think about the power of history as a vehicle for discussion, and how students—even when they disagree (especially when they disagree)—learn to talk to one another.

The author is grateful to the Educational Opportunity Program, which recruited students from its student community and provided advising support; the Undergraduate Colleges for hosting this course; the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching, which used surveys and in-class observations to assess learning outcomes; teaching assistant Ayana Jackson; and associate professor Jennifer Anderson, who provided thoughtful feedback and guidance on the course content.

Richard H. Tomczak is the director of faculty engagement in undergraduate education and a research assistant professor in the history department at Stony Brook University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.