The following is a list of recipients of the various awards, prizes, and honors presented during the 120th annual meeting of the American Historical Association on Friday, January 6, 2006, in the Loews Philadelphia, Millennium Hall.

Awards for Scholarly Distinction

In 1984 the Council of the American Historical Association established the American Historical Association Award for Scholarly Distinction. Each year a nominating jury, composed of the president, president-elect, and immediate past president, recommends to the Council of the Association up to three names for the award. Nominees are senior historians of the highest distinction in the historical profession who have spent the bulk of their professional careers in the United States. Previous awards have gone to Nettie Lee Benson, Woodrow Borah, Alfred D. Chandler Jr., Thomas D. Clark, Angie Debo, Helen G. Edmonds, Elizabeth Eisenstein, Peter Gay, Felix Gilbert, John Whitney Hall, Tulio Halperín-Donghi, John Higham, H. Stuart Hughes, Margaret Atwood Judson, Nikkie R. Keddie, George F. Kennan, Paul Oskar Kristeller, Gerhart B. Ladner, Gerda Lerner, Wallace T. MacCaffrey, Ramsay MacMullen, Ernest R. May, Arno J. Mayer, Richard P. McCormick, August Meier, Edmund Morgan, George L. Mosse, Robert O. Paxton, John G. A. Pocock, Earl Pomeroy, H. Leon Prather Sr., Benjamin Quarles, Edwin O. Reischauer, Robert V. Remini, Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, Caroline Robbins, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Carl E. Schorske, Benjamin I. Schwartz, Kenneth M. Setton, Kenneth M. Stampp, Chester G. Starr, Barbara and Stanley Stein, Lawrence Stone, Sylvia L. Thrupp Strayer, Merze Tate, Emma Lou Thornbrough, Brian Tierney, Eugen Weber, Gerhard Weinberg, and George R. Woolfolk.

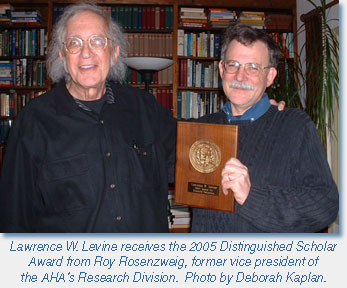

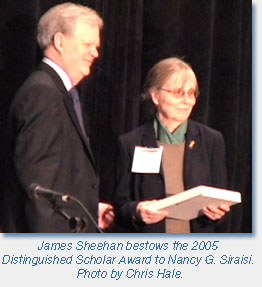

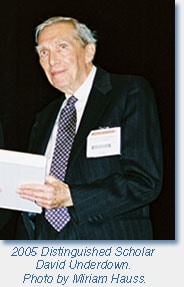

Joining this distinguished list are Lawrence W. Levine (George Mason Univ. and Univ. of California at Berkeley), Nancy G. Siraisi (Hunter College, CUNY), and David Underdown (Yale Univ.).

In a career of over 40 years, Lawrence W. Levine has made exceptional scholarly contributions. He is distinguished by his innovative interdisciplinary analysis of the complex process of cultural transformation among America’s diverse peoples.

In a career of over 40 years, Lawrence W. Levine has made exceptional scholarly contributions. He is distinguished by his innovative interdisciplinary analysis of the complex process of cultural transformation among America’s diverse peoples.

His first book, Defender of the Faith: William Jennings Bryan: The Last Decade, 1915–1925 (Oxford Univ. Press, 1965), helped re-frame the historiography of the American 1920s. His analysis of Bryan’s fundamentalism brought fresh perspectives on the cultural conflicts of the decade. The pathbreaking Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom (Oxford Univ. Press, 1977) used what were then unusual sources—humor, folklore, and music—to explore black culture and its relationship to the mainstream, and gave new insights into the nature of cultural creation itself. As he put it, “Culture is not a fixed condition but a process: the product of interaction between the past and present.”

Other books furthered the project of exploring cultural processes.Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Harvard Univ. Press, 1988) examined the way in which opera, theater, and museums became largely the cultural property of elites. The Opening of the American Mind: Canons, Culture, and History (Beacon Press, 1996) challenged conservatives’ critiques of multiculturalism in the academy by bringing rigorous historical scholarship to the debate about the canon. His most recent book, The People and the President: America’s Conversation with FDR (Beacon Press, 2002), written with Cornelia Levine, followed Levine’s customary pattern of exhaustive research to explore the responses of ordinary Americans to FDR’s fireside chats.

His accomplishments have earned him an international reputation and numerous honors, including the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (1983–88) and the presidency of the Organization of American Historians (1992–93). In his long career at the University of California at Berkeley (1962–94), where he was the Margaret Bryne Professor History, and at George Mason University (1994–present), he has mentored scores of young historians and serves as a model for innovative scholarship and committed teaching. The AHA Award for Scholarly Distinction is a fitting recognition of Lawrence Levine’s outstanding contributions.

Nancy G. Siraisi has been a prolific and leading scholar in the history of medicine and science of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Her research has ranged widely across these two distinct fields, from her first book on the university curriculum in medieval Padua to her current work on the role of doctors in history-writing in the Renaissance.

Nancy G. Siraisi has been a prolific and leading scholar in the history of medicine and science of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Her research has ranged widely across these two distinct fields, from her first book on the university curriculum in medieval Padua to her current work on the role of doctors in history-writing in the Renaissance.

Through her numerous publications and professional activities Nancy Siraisi aided the growth of the history of science and medicine when these fields were still small, but as they grew larger and more independent, she also fostered the continued close interaction of these fields with “mainstream” history, notably through her faithful teaching of general medieval and Renaissance history and her insistence on careful contextualization. In her practice of intellectual history Nancy Siraisi attends not only to texts and textual traditions, but also to individual lives and daily practices, institutional settings and social relations, disciplinary distinctions and literary genres. Her award-winning Taddeo Alderotti and His Pupils: Two Generations of Italian Medical Learning (Princeton Univ. Press, 1981) reconstructed from extensive manuscript research the teaching of medicine in 13th- and 14th-century Bologna. In Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching of Italian Universities after 1500 (Princeton Univ. Press, 1987) she traced the longevity of the Canon of Avicenna through commentaries in Italian universities after 1500. In The Clock and the Mirror: Girolamo Cardano and Renaissance Medicine (Princeton Univ. Press, 1997) she illuminated the medical activities of the sixteenth-century Italian physician Girolamo Cardano, from his authorship to his bedside practices. Nancy Siraisi’s most widely read book, Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1990) is universally praised as a model of a textbook.

Nancy Siraisi received her BA from Oxford University, then moved to New York where she spent her career in New York City’s public university system: she received her PhD from the Graduate Center and taught in the Department of History at Hunter College from 1970 until her retirement as Distinguished Professor in 2003. The most critical scholars in Europe and America hold her work in the highest esteem.

For nearly 50 years, David Underdown has been an important voice in the history of early modern England. In a famously contentious field, he was rare in having the respect of those on all sides of the various controversies. His standing was due to his unswerving commitment to scholarly inquiry, his exhaustive research, and scrupulous honesty in his treatment of sources. These were joined, in the course of his career, with the willingness to explore new conceptual models and approaches to history. He has always seen historical knowledge as a process, and has never thought he had all the answers. This intellectual humility has enabled him to write a series of books and articles that continue—even after 30 years—to be the starting point for discussions of subjects ranging from elite and popular allegiance during the Civil War, the role of gender in the social order, the impact of Puritanism in English communities, and even the history of eighteenth-century cricket.

For nearly 50 years, David Underdown has been an important voice in the history of early modern England. In a famously contentious field, he was rare in having the respect of those on all sides of the various controversies. His standing was due to his unswerving commitment to scholarly inquiry, his exhaustive research, and scrupulous honesty in his treatment of sources. These were joined, in the course of his career, with the willingness to explore new conceptual models and approaches to history. He has always seen historical knowledge as a process, and has never thought he had all the answers. This intellectual humility has enabled him to write a series of books and articles that continue—even after 30 years—to be the starting point for discussions of subjects ranging from elite and popular allegiance during the Civil War, the role of gender in the social order, the impact of Puritanism in English communities, and even the history of eighteenth-century cricket.

As a teacher—at the University of the South, the University of Virginia, Brown University, and Yale University—the intellectual modesty that shaped Underdown’s scholarship also inspired students. Like his own mentor, Christopher Hill, he has not created a school or movement, but he exemplified honest historical inquiry. His students, and the wider circle of those he has influenced, have followed a wide range of subjects in early modern English history, and have made major contributions to political, social, and cultural history.

David Underdown has always been a historian’s historian, more interested in exploring the past than personal glory. He is still interested in, and puzzled by, the world of early modern England, and so he continues his writing and research. In this, as in so much else, he offers a model of scholarly commitment for all those who know him.

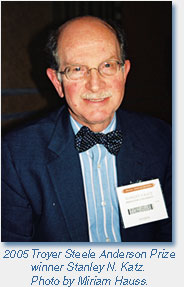

The Troyer Steele Anderson Prize

Established in 1963 through a bequest by Frank Maloy Anderson, a longtime AHA member, this prize is awarded for outstanding contributions to the advancement of the purposes of the Association and has been conferred just four times. The Council selects a recipient based upon the recommendations of the Professional Division, which serves as a nominating jury in consultation with the Research and Teaching Divisions.

The Anderson Prize was awarded to Stanley N. Katz of Princeton University. Over many years Stan Katz has taught by example and by his writings much of what we know about civic duty and responsibility. In his leadership at the American Historical Association, as well as in his presidencies of the American Council of Learned Societies, the American Society for Legal History, and the Organization of American Historians, he has exemplified the role of professional citizenship in an extraordinary way.

The Anderson Prize was awarded to Stanley N. Katz of Princeton University. Over many years Stan Katz has taught by example and by his writings much of what we know about civic duty and responsibility. In his leadership at the American Historical Association, as well as in his presidencies of the American Council of Learned Societies, the American Society for Legal History, and the Organization of American Historians, he has exemplified the role of professional citizenship in an extraordinary way.

Even a simple list of his service to the AHA is daunting: Professor Katz served as vice president of the Research Division and member of the Council, 1997–2000; as a member of the Committee on International Historical Activities; as chair of the Littleton-Griswold Prize Committee and the Beveridge Book Prize Committee; and as a member of the Research Division. He currently chairs the AHA’s Task Force on Intellectual Property and represents the Association on the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. His deep commitment to the improvement of history teaching has been a sustained one, going back at least 20 years to the Association’s involvement in several efforts to improve K–12 education: he chaired the History Teaching Alliance in the late 1980s and he was a key member of the Committee on Graduate Education, which produced a major study of doctoral education that is already having an impact on graduate programs throughout the nation. He is now playing a major role in a new history education policy initiative just launched by the National History Center. As the Association has struggled to find its way among new developments in electronic technology relating to the publication of historical research, he has been an indefatigable source of inspiration, guidance, and information, particularly in the development of the History Cooperative.

This partial record of his formal service to the Association only begins to explain the critical role Stan Katz has played in the AHA. Just as Chaucer’s scholar would “gladly learn and gladly teach” he has gladly shared his knowledge and expansive professional network with the Association. His membership in the American Historical Association is one of its most significant assets.

Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award

Established in 1986, the Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award recognizes outstanding teaching and advocacy for history teaching at two-year, four-year, and graduate colleges and universities, by commending an inspiring teacher whose pedagogical techniques and mastery of subject matter make a lasting impression and substantial difference to students of history. The prize is named for the late Eugene Asher, who was for many years a leading advocate for history teaching. The Society for History Education (SHE) shares with the AHA sponsorship of the award. Members of the AHA and SHE submit nominations to the Committee on Teaching Prizes.

The 2005 honoree is Eileen Scully of Bennington College. At Bennington, Scully has developed a seies of thinking-and-doing courses to tie history content to performance. Her Building the Museum of American Slavery course offers students an opportunity to collaboratively design and fill such a museum while generating within them the imperative to learn about slavery. In her course, The Journey, her students travel the world at a given historical moment. Her current responsibilities include supervision of a teacher training program at Bennington, reflecting her commitment to the training of dedicated history teachers for our public schools.

The Beveridge Family Teaching Award

Established in 1995, this prize honors the Beveridge family’s long-standing commitment to the AHA and to K–12 teaching. Friends and family members endowed this award to recognize excellence and innovation in elementary, middle, and secondary school history teaching, including career contributions and specific initiatives. The individual can be recognized either for individual excellence in teaching or for an innovative initiative applicable to the entire field. It is offered on a two-cycle rotation: in even-numbered years, to an individual; in odd-numbered years, to a group. The prize was first offered in 1996, and in 2005 it is awarded to a group of teachers.

Established in 1995, this prize honors the Beveridge family’s long-standing commitment to the AHA and to K–12 teaching. Friends and family members endowed this award to recognize excellence and innovation in elementary, middle, and secondary school history teaching, including career contributions and specific initiatives. The individual can be recognized either for individual excellence in teaching or for an innovative initiative applicable to the entire field. It is offered on a two-cycle rotation: in even-numbered years, to an individual; in odd-numbered years, to a group. The prize was first offered in 1996, and in 2005 it is awarded to a group of teachers.

President-elect Linda Kerber announced that the 10th recipient of the Beveridge Family Teaching Prize is the American History Team of West Springfield High School in Springfield, Virginia. The team’s members are Laurie Fischer, Ronald C. Maggiano, Tamara Ogden, James Percoco, and Margaret Tran. These teachers strive to go beyond the traditional curriculum requirements of an increasingly test-driven, standards-based environment. One of the teachers described the team’s approach to teaching history with a quote from William Butler Yeats: “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” The teachers use original and creative methods to inspire their students, who then leave their classes with a passion for history that they carry with them beyond high school into life.

William Gilbert Award

Named in memory of William Gilbert, a longtime AHA member and distinguished scholar-teacher at the University of Kansas, the biennial Gilbert Award recognizes outstanding contributions to the teaching of history through the publication of journal and serial articles. The prize was endowed by a generous gift from Mrs. Gilbert. Pieces written by members of the AHA and published in the United States during the two years previous to the award are eligible for consideration. Also, journals, magazines, and other serials that publish works on the teaching of history, including methodology and pedagogical theory, may submit nominations

The 2005 Gilbert Award was presented to Mark C. Carnes of Barnard College for his article “Inciting Speech,” which appeared in Change Magazine (March/April 2005). The committee’s citation reads: “This article describes Professor Carnes’s efforts in a program he initiated at Barnard called ‘Reacting to the Past.’ Here students learn ideas by discussing and debating them. ‘They learn about the past by reliving it,’ said Carnes. Since its initiation at Barnard, numerous colleges and universities across the country have adopted the program.”

Gutenberg-e Prizes

Gutenberg-e Prizes have been offered each year since 1999 for the best history dissertations in specified fields. Thanks to a generous grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the AHA offered these prizes in collaboration with Columbia University Press, which publishes the prizewinning manuscripts in an electronic form. Each prizewinner receives a $20,000 fellowship grant to meet the costs of revising the manuscript for publication. The most recent Gutenberg-e competition (the last, in its present form) was open for dissertations in all fields of history, and the prizes were awarded to:

Sherry Fields (Univ. of California at Davis), “Pestilence and Headcolds: Encountering Illness in Colonial Mexico” (Univ. of California at Davis dissertation). Fields provides a useful survey of a seriously neglected field in colonial Latin American history. Her work explores cultures of health and illness in colonial Mexico as illuminated by popular beliefs and practices following the encounter of indigenous and European medical traditions. Her use of ex-votos as sources is especially interesting, but the work spans a range of subject areas, including the history of medicine, the history of the body, the history of science, and the history of religion.

Ronda M. Gonzales (Univ. of Texas at San Antonio), “Continuity and Change: Thought, Belief, and Practice in the History of the Ruvu Peoples of Central East Tanzania, c. 200 B.C. to A.D. 1800” (UCLA dissertation). Gonzales relies principally on historical linguistics as supplemented by field research and occasional archaeological data in developing a complex understanding of linguistic-cultural-historical development in east Africa. The scope of her work is breathtaking, and it is quite impressive that she has been able to coax ostensibly unpromising and uncooperative data to reveal so much. Her research has filled a gap in the history of Tanzania’s precolonial past, which is ethnographically rich but has been little studied historically.

Sarah Gordon (SUNY, Purchase College), “‘Make It Yourself’: Home Sewing, Gender and Culture, 1890–1930” (Rutgers Univ.-New Brunswick dissertation). This manuscript rests on a fascinating body of material as it explores documents pertaining to home sewing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The author shows that sewing activities both supported and undermined traditional domestic ideals. Gordon argues that the portrayal of home sewing shifted from a useful form of household labor to a way to nurture a family and cultivate attractiveness. She also demonstrates the role of sewing in altering conceptions of respectability through an examination of sports clothing. In the process, she makes a small slice of the past speak to large issues.

Shah Mahmoud Hanifi (James Madison Univ.), “Inter-Regional Trade and Colonial State Formation in Nineteenth-Century Afghanistan” (Univ. of Michigan dissertation). Hanifi focuses on trade, literacy, and state building in locating para-colonial Afghanistan in the contexts of imperial and capitalist history. He juggles political, cultural, and economic considerations. He adroitly and persuasively balances theoretical perspectives with empirical data, and draws on an impressive blend of archival, narrative, and oral historical sources. In a field in which there is so little in the way of recent historical literature, this is an important effort.

Robert Kirkbride (Univ. of Illinois at Chicago), “Architecture and Memory: The Renaissance Studioli of Federico da Montefeltro” (McGill Univ. dissertation). Kirkbride examines the two studioli built in the 1470s by Federico da Montefeltre to show how the architecture and decoration of the two rooms reflected and contributed to Renaissance discussions of intellectual activity, statecraft, and education. He demonstrates that these rooms embodied theories of the art of memory, which Renaissance thinkers regarded as the foundation of all intellectual endeavors. Memory supplied the materials of oration, of reflection, and of theorizing. He brings an art historian’s tools to this study, which greatly enhances his ability to explain the artistic programs of the two spaces within a substantial intellectual history. The dissertation is a tour de force of scholarship and writing. It is full of insights, imaginative in its approach, very analytical, and yet very elegantly written.

Jennifer Langdon-Teclaw (Univ. of Illinois at Chicago), “Caught in the Crossfire: Anti-Fascism, Anti-Communism and the Politics of Americanism in the Hollywood Career of Adrian Scott” (SUNY, Binghamton dissertation). This manuscript explores the politics of the Cold War by investigating the career of the Hollywood producer Adrian Scott and the fortunes of his controversial film Crossfire. The author does a very nice job with the narrative, and in reconstructing the context in which the Left operated in Hollywood. From the start, it exhibits a refreshing energy as the author connects her story to matters of gender and ethnicity as well as anti-communism.

Laura Mitchell (Univ. of California at Irvine), “Contested Terrains: Property and Labor on the Cedarberg Frontier, 1725–c. 1830” (UCLA dissertation). Mitchell combines archaeological and historical findings to argue convincingly for the overlap of “prehistorical” (i.e., hunting and gathering Khoisan populations) and historical (e.g., slaves of various backgrounds and settlers of European descent) periods. She takes on those who focus on slavery on the Cape and who lump together various forms of servitude. She looks at the role of kin and family networks in securing Dutch settlers, thereby identifying Dutch women’s contributions and roles. She has done solid research and takes on big issues.

Bin Yang (National Univ. of Singapore), “Between Winds and Clouds: The Making of Yunnan (Second Century BCE-Twentieth Century CE)” (Northeastern Univ. dissertation). Yang takes “a global and long-term perspective on a local past.” Criticizing China-centric studies of southwestern China, he looks from Yunnan outward, locating the region’s central role in the Southwest Silk Road, and its transformations in terms of economy, administration, populations, and sense of ethnic identity. He seeks to show that a world history approach is stronger at explaining local dynamics than a national approach. The arguments are provocative, original, and engaging, and he is remarkably successful in covering such an extended period.

John E. O’Connor Film Award

In recognition of his exceptional role as a pioneer in both teaching and research regarding film and history, the American Historical Association established this award in honor of John E. O’Connor of the New Jersey Institute of Technology. The award seeks to recognize outstanding interpretations of history through the medium of film or video. Essential elements are stimulation of thought, imaginative use of the media, effective presentation of information and ideas, sensitivity to modern scholarship, and accuracy. The production should encourage viewers to ask questions about historical interpretations as well as make a contribution to the understanding of history

The 13th O’Connor Award was presented to Proteus: A Nineteenth Century Vision (Night Fire Films, Inc.), producer/writer/director/editor: David Lebrun. This film uses the life of biologist and artist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) to explore his era’s fascination with the undersea world. Employing artful animation, it presents Haeckel’s drawings of sea creatures plus other historical images accompanied by insightful narration and a poetic musical score. These address Haeckel’s lifelong effort to reconcile his research supporting theories of evolution with his spiritual sensibilities. This haunting portrait of 19th-century mentalities appears both foreign and familiar to our own era’s anxieties.

Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award

In recognition of Nancy Lyman Roelker’s role as a teacher, scholar, and committed member of the historical profession, and on the occasion of her 75th birthday, friends, colleagues, and former students established the Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award. The annual award recognizes and encourages a special quality exemplified by Professor Roelker through the human component in her teaching of history.

In recognition of Nancy Lyman Roelker’s role as a teacher, scholar, and committed member of the historical profession, and on the occasion of her 75th birthday, friends, colleagues, and former students established the Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award. The annual award recognizes and encourages a special quality exemplified by Professor Roelker through the human component in her teaching of history.

Mentoring should encompass not only a belief in the value of the study of history but also a commitment to and a love of teaching it to students regardless of age or career goals. Advising is an essential component, but it also combines a consistent personal commitment by the mentor to the student as a person. Offering a human alternative, frequently in quiet and unacknowledged ways, mentors like Roelker believe that the essence of history lies in its human scope. With this award, the American Historical Association attests to the special role of mentors to the future of the historical profession.

John F. Howes (Univ. of British Columbia) and Mary Logan Rothschild (Arizona State Univ.) are the recipients of the 14th annual Roelker Mentorship Award.

Revered as their “onshi” (“master”), John F. Howes embodies one-on-one lifetime commitments to his students. From service on General Douglas MacArthur’s postwar staff in Japan through recent recognition by the Japanese government, Howes has served as a virtual cultural ambassador between the West and Japan. Perhaps the foremost pioneer of Japanese history in Canada, he inspired generations of undergraduates at the University of British Columbia to study Japanese and East Asian history. Then he helped them study and live in Japan, establish careers, and weather personal crises. As one of his students writes, Howes and his wife Lyn made generations of students part of their “extended family.”

Mary Logan Rothschild has pioneered the study of women’s history in her university, state, and country. Not only has she mentored students and younger faculty at Arizona State University, she has also established wide networks within Arizona and beyond to cultivate women’s history. She has given 350 presentations in her state promoting the study of women’s pasts, a considerable number of them encouraging oral history. As one letter states, “Mary has the ability to excite students literally of all ages not just about what history tells us about the past, but about doing history in the present. As with all great mentors, the teaching never really ends.” She has also fought for diversity in a number of areas on her campus as well as in the historical profession.

Honorary Foreign Member

At its second annual meeting in Saratoga in 1885, the newly appointed Committee on Nominations for Honorary Membership introduced a resolution that was adopted, which appointed Leopold von Ranke as the first honorary foreign member. Previously biennial, selection is now annual, and honors a foreign scholar who is distinguished in his or her field and who has “notably aided the work of American historians.”

President-elect Kerber announced the addition of Nikolai Nikolaevich Bolkhovitinov of the Institute of World History, Russian Academy of Sciences, to the long list of distinguished foreign scholars who have been selected to be honorary foreign members, and read the following citation: “Since his first publications amid the heightened Cold War tensions of the late 1950s, Bolkhovitinov has been a dedicated promoter of scholarly values in a field rife with political conflict. His eight monographs and four edited collections (not to mention his fifty-plus articles in scholarly journals) have covered a variety of fields, including American foreign relations, the Russian colony in North America, and early American-Russian relations. These achievements have been widely recognized in his home country, where Bolkhovitinov is a full member of the Academy of Sciences and director of its Center for North American Studies; he also received the State Award of the Russian Federation in 1997 for his life’s work. After serving for decades on the editorial boards of the most important Russian-language historical journals, Bolkhovitinov became a founding member of the Journal of American History‘s international editorial board in 1992. This is only one of his many connections to U.S.-based historians; he has made an extraordinary contribution to scholarly exchange and international understanding through his many trips to the United States and his hospitality and hard work in Moscow. The AHA is proud to bestow an Honorary Foreign Membership on Nikolai Nikolaevich Bolkhovitinov.”

Book Awards

The following prizes were announced for the year 2005. The prize citations are recorded in the following pages.

Herbert Baxter Adams Prize

Maureen Healy (Oregon State Univ.), for Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire: Total War and Everyday Life in World War I (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). In this richly textured account of life in Vienna during World War I, Maureen Healy locates the social disintegration of the Austrian Empire in the daily experiences and communal conflicts of Vienna’s inhabitants. Through impressive research and subtle readings of mundane events, she not only offers a vivid account of war mobilization, but also reinterprets Austrian citizenship and wartime politics by illustrating how women, children, and left-at-home men faced off against the state and imagined their political identities.

Maureen Healy (Oregon State Univ.), for Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire: Total War and Everyday Life in World War I (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). In this richly textured account of life in Vienna during World War I, Maureen Healy locates the social disintegration of the Austrian Empire in the daily experiences and communal conflicts of Vienna’s inhabitants. Through impressive research and subtle readings of mundane events, she not only offers a vivid account of war mobilization, but also reinterprets Austrian citizenship and wartime politics by illustrating how women, children, and left-at-home men faced off against the state and imagined their political identities.

Prize in Atlantic History

Londa Schiebinger (Stanford Univ.), for Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Harvard Univ. Press, 2004).Plants and Empire is a pathbreaking study of European efforts to “mine” the biological riches of the tropics, especially the peacock flower that native peoples and Africans used as an abortifacient in the Caribbean. In addition to showing how Europeans obtained previously inaccessible knowledge, Schiebinger explains why some scientific discoveries did not penetrate the consciousness of metropolitan Europeans. Beautifully written and meticulously researched, Schiebinger’s book will shape thinking about science and empire for years to come.

George Louis Beer Prize

Carole Fink (Ohio State Univ.), for Defending the Rights of Others: The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878–1938 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). Based on astonishing archival research in eleven countries, Carole Fink’s pathbreaking book, Defending the Rights of Others, integrates the too often separate histories of international relations, national identity, minority rights, and domestic politics. Focusing on the 60 years following the 1878 Congress of Berlin, Fink deftly analyzes how the Great Powers, the defenders of oppressed groups—particularly the Jews, and minority states—wrestled with rival national interests and ambivalent, contradictory concerns with universal human rights.

Carole Fink (Ohio State Univ.), for Defending the Rights of Others: The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878–1938 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). Based on astonishing archival research in eleven countries, Carole Fink’s pathbreaking book, Defending the Rights of Others, integrates the too often separate histories of international relations, national identity, minority rights, and domestic politics. Focusing on the 60 years following the 1878 Congress of Berlin, Fink deftly analyzes how the Great Powers, the defenders of oppressed groups—particularly the Jews, and minority states—wrestled with rival national interests and ambivalent, contradictory concerns with universal human rights.

Albert J. Beveridge Award

Melvin Patrick Ely (Coll. of William and Mary), for Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War (Knopf, 2004). In this beautifully crafted history of a community of free blacks and their abolitionist former masters in antebellum Virginia, Melvin Ely finds that black freedmen enjoyed a remarkable degree of political and economic autonomy, despite increasingly restrictive laws deployed against them. Ely’s account of freedmen like Syphax Brown successfully suing white defendants is not only fascinating, but also provides new perspectives on the history of slavery and the relationship between ideology and experience within southern race relations.

Melvin Patrick Ely (Coll. of William and Mary), for Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War (Knopf, 2004). In this beautifully crafted history of a community of free blacks and their abolitionist former masters in antebellum Virginia, Melvin Ely finds that black freedmen enjoyed a remarkable degree of political and economic autonomy, despite increasingly restrictive laws deployed against them. Ely’s account of freedmen like Syphax Brown successfully suing white defendants is not only fascinating, but also provides new perspectives on the history of slavery and the relationship between ideology and experience within southern race relations.

James Henry Breasted Prize

Callie Williamson (independent scholar), for The Laws of the Roman People: Public Law in the Expansion and Decline of the Roman Republic (Univ. of Michigan Press, 2005). This intellectually powerful and highly original book examines Roman expansion through the lens of public lawmaking, the process of negotiation and debate by which citizen assemblies resolved conflict and expressed consensus. Williamson incisively examines how problems of expansion were managed, and boldly argues that in the end it was expansion itself—both of the electorate and its leadership—that overwhelmed the problem-solving capacities of public lawmaking and led to the breakdown of the Republic.

Callie Williamson (independent scholar), for The Laws of the Roman People: Public Law in the Expansion and Decline of the Roman Republic (Univ. of Michigan Press, 2005). This intellectually powerful and highly original book examines Roman expansion through the lens of public lawmaking, the process of negotiation and debate by which citizen assemblies resolved conflict and expressed consensus. Williamson incisively examines how problems of expansion were managed, and boldly argues that in the end it was expansion itself—both of the electorate and its leadership—that overwhelmed the problem-solving capacities of public lawmaking and led to the breakdown of the Republic.

John H. Dunning Prize

Jon T. Coleman (Univ. of Notre Dame), for Vicious: Wolves and Men in America (Yale Univ. Press, 2004). A wry, beautifully written book that examines why people attacked wolves and how this beast has recently become a protected symbol of wilderness. Coleman weaves together history, folklore, and biology to study how and why this violence moved far beyond the mere protection of livestock. The study of the escalating fear of wolves sheds light on a variety of characters and key moments over the centuries and throughout the continent, while also enriching our understanding of contemporary beliefs and practices about animals.

Jon T. Coleman (Univ. of Notre Dame), for Vicious: Wolves and Men in America (Yale Univ. Press, 2004). A wry, beautifully written book that examines why people attacked wolves and how this beast has recently become a protected symbol of wilderness. Coleman weaves together history, folklore, and biology to study how and why this violence moved far beyond the mere protection of livestock. The study of the escalating fear of wolves sheds light on a variety of characters and key moments over the centuries and throughout the continent, while also enriching our understanding of contemporary beliefs and practices about animals.

John Edwin Fagg Prize

Brian A. Catlos (Univ. of California at Santa Clara), for The Victors and the Vanquished: Christians and Muslims of Catalonia and Aragon, 1050–1300 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). This meticulously researched and lucid analysis uses sources in Latin, Arabic, and several other languages to analyze how Muslims retained their identity under Christian rule. In the encounter, both societies adapted and changed to live side by side.

Brian A. Catlos (Univ. of California at Santa Clara), for The Victors and the Vanquished: Christians and Muslims of Catalonia and Aragon, 1050–1300 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). This meticulously researched and lucid analysis uses sources in Latin, Arabic, and several other languages to analyze how Muslims retained their identity under Christian rule. In the encounter, both societies adapted and changed to live side by side.

Aline Helg (Univ. of Geneva) for Liberty and Equality in Caribbean Colombia, 1770–1835 (Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2004). This study is an unusually important contribution to circum-Caribbean studies and Colombian history. Its main question—why race did not become an organizing principle in northern Colombia, as it did in several Afro-Caribbean countries—is deeply researched, interpreted in multiple contexts, and appraised in a fine, comparative conclusion.

John K. Fairbank Prize

Ruth Rogaski (Vanderbilt Univ.), for Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China (Univ. of California Press, 2004). Ruth Rogaski’s elegantly argued and richly documented account of late 19th- and early 20th-century colonial encounters in the Chinese city of Tianjin demonstrates how the commitment to Western notions of a state-sponsored germ-free “hygienic modernity” emerged from indigenous concepts of “guarding life.” Tracing debates over diet, disease, medicine, science, and sanitation, she makes clear Japan’s crucial role, and tells a fresh and compelling story of the relationship between modernity and empire.

Ruth Rogaski (Vanderbilt Univ.), for Hygienic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China (Univ. of California Press, 2004). Ruth Rogaski’s elegantly argued and richly documented account of late 19th- and early 20th-century colonial encounters in the Chinese city of Tianjin demonstrates how the commitment to Western notions of a state-sponsored germ-free “hygienic modernity” emerged from indigenous concepts of “guarding life.” Tracing debates over diet, disease, medicine, science, and sanitation, she makes clear Japan’s crucial role, and tells a fresh and compelling story of the relationship between modernity and empire.

Herbert Feis Award

Mark Landsman (independent scholar), for Dictatorship and Demand: The Politics of Consumerism in East Germany (Harvard Univ. Press, 2005). Mark Landsman’s fascinating study Dictatorship and Demand explores the role of consumerism in East Germany in the period between the Berlin Blockade and the construction of the Berlin Wall. Landsman shows how in East Germany Soviet-inspired “productivism” competed with “the creeping challenge” of postwar mass consumption in the West. Landsman’s strong, meticulous and lucidly presented scholarship provides an unusually rich orientation to the political and economic complexities of consumerism—as a source of conflict within the GDR and as a trigger for Cold War competition.

Morris D. Forkosch Prize

Bernard Porter (Univ. of Newcastle), for The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004). The Absent-Minded Imperialists is an engaging study that questions prevailing assumptions about the effects empire “must have” had on Britain. Porter’s research into politics and culture finds much less of an imperial effect than might have been imagined and allows him to argue for a sophisticated alternative view with grace, wit, and telling detail. The book is a major accomplishment.

Bernard Porter (Univ. of Newcastle), for The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004). The Absent-Minded Imperialists is an engaging study that questions prevailing assumptions about the effects empire “must have” had on Britain. Porter’s research into politics and culture finds much less of an imperial effect than might have been imagined and allows him to argue for a sophisticated alternative view with grace, wit, and telling detail. The book is a major accomplishment.

Leo Gershoy Award

Pamela H. Smith (Columbia Univ.), for The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2004). Pamela Smith and the University of Chicago Press have produced a stunning work that treats art, craft, and science from the artisan’s perspective. It is bold, persuasive, beautifully illustrated, and admirably broad. It illuminates how people worked, saw, thought, and positioned themselves in Northern European society over two centuries, revealing connections between the ways artisans and natural philosophers understood and represented reality. It makes crucial conceptual linkages, teaches important lessons, and gives great pleasure in the process.

Pamela H. Smith (Columbia Univ.), for The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2004). Pamela Smith and the University of Chicago Press have produced a stunning work that treats art, craft, and science from the artisan’s perspective. It is bold, persuasive, beautifully illustrated, and admirably broad. It illuminates how people worked, saw, thought, and positioned themselves in Northern European society over two centuries, revealing connections between the ways artisans and natural philosophers understood and represented reality. It makes crucial conceptual linkages, teaches important lessons, and gives great pleasure in the process.

J. Franklin Jameson Award

Ronald Hoffman, Sally D. Mason, and Eleanor S. Darcy (Omohundro Institute of Early American History), for Dear Papa, Dear Charley: The Peregrinations of a Revolutionary Aristocrat (Maryland Historical Society, Maryland State Archives, and Univ. of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2001). The work is a rich collection of letters, an intimate family history that narrates the epochal changes that transformed Maryland and the Anglo-American world during the revolutionary era. These superbly edited letters between a father and his son, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only Roman Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, illuminate not simply their own private lives but also enduring central questions of religious beliefs, civil rights, and politics in the American republic.

Ronald Hoffman, Sally D. Mason, and Eleanor S. Darcy (Omohundro Institute of Early American History), for Dear Papa, Dear Charley: The Peregrinations of a Revolutionary Aristocrat (Maryland Historical Society, Maryland State Archives, and Univ. of North Carolina Press for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2001). The work is a rich collection of letters, an intimate family history that narrates the epochal changes that transformed Maryland and the Anglo-American world during the revolutionary era. These superbly edited letters between a father and his son, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only Roman Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence, illuminate not simply their own private lives but also enduring central questions of religious beliefs, civil rights, and politics in the American republic.

Joan Kelly Memorial Prize

Afsaneh Najmabadi (Harvard Univ.), for Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Univ. of California Press, 2005). In this original and pathbreaking study, Najmabadi draws upon a dazzling array of sources—archival documents, poetry, novels, travel narratives, paintings, and political iconography—to explore the connections between gendered histories of sexuality and the making of Iran’s modernity. Tracing the demise of a gender-transcendent standard of beauty, among other transformations, she argues that Iranian modernity was both produced by and produced a binary heterosexuality where once had flourished various forms of homoeroticism.

Afsaneh Najmabadi (Harvard Univ.), for Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Univ. of California Press, 2005). In this original and pathbreaking study, Najmabadi draws upon a dazzling array of sources—archival documents, poetry, novels, travel narratives, paintings, and political iconography—to explore the connections between gendered histories of sexuality and the making of Iran’s modernity. Tracing the demise of a gender-transcendent standard of beauty, among other transformations, she argues that Iranian modernity was both produced by and produced a binary heterosexuality where once had flourished various forms of homoeroticism.

Littleton-Griswold Prize

Mary Sarah Bilder (Boston Coll.), for The Transatlantic Constitution: Colonial Legal Culture and the Empire (Harvard Univ. Press, 2004). This book brilliantly challenges the orthodoxy that until 1763 English authorities ignored American colonial law. Focusing on the actual practice of imperial law through 17th- and 18th-century Rhode Island, Bilder argues that legal and political dialogues created a dynamic imperial constitution out of tensions between adherence to English law and acceptance of local deviations not repudiating English law. London then precipitated the Revolution by resolving tension between the two principles in favor of more uniform English law.

J. Russell Major Prize

Barbara Diefendorf (Boston Univ.), for From Penitence to Charity: Pious Women and the Catholic Reformation in Paris (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004). This evocative study of female spirituality in Paris offers an important revision of our understanding of the Catholic Reformation. For Diefendorf, Catholic women were not oppressed victims of a misogynistic clergy, but patronesses and founders of religious communities that increasingly emphasized service to the poor as their central mission. The importance of the movement she studies and the quality of her analysis make Diefendorf’s book essential reading for all historians of early modern Europe.

Barbara Diefendorf (Boston Univ.), for From Penitence to Charity: Pious Women and the Catholic Reformation in Paris (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004). This evocative study of female spirituality in Paris offers an important revision of our understanding of the Catholic Reformation. For Diefendorf, Catholic women were not oppressed victims of a misogynistic clergy, but patronesses and founders of religious communities that increasingly emphasized service to the poor as their central mission. The importance of the movement she studies and the quality of her analysis make Diefendorf’s book essential reading for all historians of early modern Europe.

Helen and Howard R. Marraro Prize

Thomas V. Cohen (York Univ.), for Love and Death in Renaissance Italy (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2004). Through microhistorical analysis of court records from 16th-century Rome, Cohen opens a peephole onto intimate life, allowing us to glimpse something of the values and assumptions that motivated the deeds, and the words, of early modern women and men. Poignant stories, told with flair and in a variety of genres, are interlaced with the author’s insightful reflections on the tension between intimacy and strangeness that perforce characterizes historians’ encounters with individuals in the past.

Thomas V. Cohen (York Univ.), for Love and Death in Renaissance Italy (Univ. of Chicago Press, 2004). Through microhistorical analysis of court records from 16th-century Rome, Cohen opens a peephole onto intimate life, allowing us to glimpse something of the values and assumptions that motivated the deeds, and the words, of early modern women and men. Poignant stories, told with flair and in a variety of genres, are interlaced with the author’s insightful reflections on the tension between intimacy and strangeness that perforce characterizes historians’ encounters with individuals in the past.

George L. Mosse Prize

Jonathan Sheehan (Indiana Univ.), for The Enlightenment Bible: Translation, Scholarship, Culture (Princeton Univ. Press, 2005). Sheehan maps the Bible’s transformation from transcendent scripture to cultural touchstone in German and British culture across the 18th and 19th centuries. This book’s remarkable scope and analysis demonstrate the importance of debates about the Bible in the Age of Reason. Well-written and finely researched, Sheehan’s book will reframe scholarly discussions of religion and modernity.

Jonathan Sheehan (Indiana Univ.), for The Enlightenment Bible: Translation, Scholarship, Culture (Princeton Univ. Press, 2005). Sheehan maps the Bible’s transformation from transcendent scripture to cultural touchstone in German and British culture across the 18th and 19th centuries. This book’s remarkable scope and analysis demonstrate the importance of debates about the Bible in the Age of Reason. Well-written and finely researched, Sheehan’s book will reframe scholarly discussions of religion and modernity.

Wesley-Logan Prize

Melvin Patrick Ely (Coll. of William and Mary), for Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War (Knopf, 2004). In this meticulous and moving reconstruction of the history of Israel Hill, a Virginia community of free black men and women, Melvin Ely asks us to reconsider how we think about slavery and freedom. Treating former slaves and local whites as individuals with complex and contradictory perspectives, he insists that lived relations—not just laws, decrees, and pronouncements—be examined in close detail. In so doing, he persuasively shows how free blacks created meaningful lives in slavery’s shadow.

Melvin Patrick Ely (Coll. of William and Mary), for Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s through the Civil War (Knopf, 2004). In this meticulous and moving reconstruction of the history of Israel Hill, a Virginia community of free black men and women, Melvin Ely asks us to reconsider how we think about slavery and freedom. Treating former slaves and local whites as individuals with complex and contradictory perspectives, he insists that lived relations—not just laws, decrees, and pronouncements—be examined in close detail. In so doing, he persuasively shows how free blacks created meaningful lives in slavery’s shadow.