When I began work on Visualizing the Red Summer, a comprehensive digital archive, map, and timeline of riots and lynchings across the United States in 1919, my initial motivation was, honestly, frustration. I first came to know about the Red Summer not in a book or classroom, but during a spring break visit to Knoxville, Tennessee, while asking my Airbnb host about the history of the neighborhood I was staying in. A violent white lynch mob had wreaked havoc on the city in late August 1919, part of a nationwide string of violence against African Americans that summer.

I was a student in my late 30s at the time, completing my undergraduate degree at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Outraged by my ignorance of that summer (especially as a native Chicagoan, where some of the worst riots erupted), I sought more information. The same regurgitated Wikipedia information filled website after website. While I knew historic documents had to exist, almost none were digitized or discoverable in any manner, and those I could find were scattered across the country. For the average student, scholar, or interested layperson, the material was virtually inaccessible, and did not give a sense of connection to other similar events that took place that summer.

The term “Red Summer,” coined by James Weldon Johnson of the NAACP, refers to a series of more than three dozen geographically dispersed race riots, lynchings, and other violent attacks targeting African Americans in 1919. While each location’s circumstances were unique, trends and parallels emerged. Tensions between the races had been rising for a few years during the first wave of the Great Migration, with an increase in housing problems, job competition, and territorial disputes. World War I had recently ended, and African American soldiers returning home were often the subjects of attacks, sometimes at the hands of white servicemen. Although technically unconnected, the individual events likely fueled a collective mindset and fear.

I felt the need to act. Armed with my own frustration and an iPhone, I set off on a solo 7,500-mile road trip in the summer of 2015 to collect as much material as I could find related to the riots. I started by both reaching out to institutions near riot locations, as well as building off bibliographies from academic publications that did exist. Most books and articles focus on individual city’s riots, such as William M. Tuttle’s Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 (1970) or Richard C. Cortner’s A Mob Intent on Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases (1988), although they do occasionally mention violence elsewhere in the country. Journalist Cameron McWhirter’s comprehensive and well-researched Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America (2011) was also useful as I built a list of existing materials on the topic.

I designed a route to maximize my time and limited funds. Some days I would drive hours only to encounter a missing box or closed institution; on others I’d hit the jackpot and have 100 items to add in one sitting. I spent my days overwhelmed by stories from the riots: white soldiers attacking black soldiers in Bisbee, Arizona; a white mob overtaking police to lynch Will Brown at the Omaha, Nebraska, courthouse; a white jury sentencing to death sharecroppers who dared to organize in Elaine, Arkansas; and teenager Eugene Williams being stoned to death for floating into the “white” area along the shore of Chicago’s Lake Michigan.

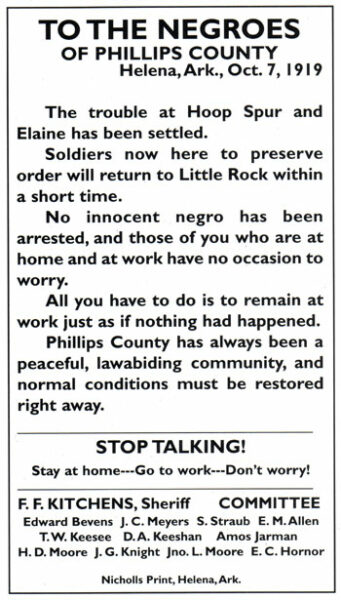

When black sharecroppers organized a union near Elaine, Arkansas, white landowners, politicians, and law enforcement, spurred by rumors of a black uprising, gunned down as many as 200 citizens in retaliation, in what is now known as the Elaine Massacre. With the few remaining African Americans in town fearful to leave their homes following the bloody events, the same white leaders behind the violent acts released notices instructing workers to “remain at work just as if nothing had happened.” Although white attackers were never charged, 122 African Americans were arrested, with 73 men charged with murder. A group dubbed the “Elaine Twelve” were convicted and sentenced to death by all-white juries for murder of a white deputy. Credit: Helena World/10/7/1919/courtesy Visualizing the Red Summer

As a public historian on this rogue acquisition journey, revisiting the events of the Red Summer felt more needed than ever—there was the impending centennial, but also current events. The murders of Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, and Laquan McDonald (a 17-year-old Chicagoan, like Eugene Williams) had sparked recent nationwide protests. Newspapers, politicians, and militarized police fueled tensions. Researching the 1919 riots in Charleston, South Carolina, I found the city still in mourning from the recent shooting at Emanuel AME Church. The week I was researching in nearby Columbia, Bree Newsome was making history with her defiant flagpole climb to remove the Confederate flag flying in front of the South Carolina state capitol building. It was hard to miss the parallels, which made my work seem even more urgent.

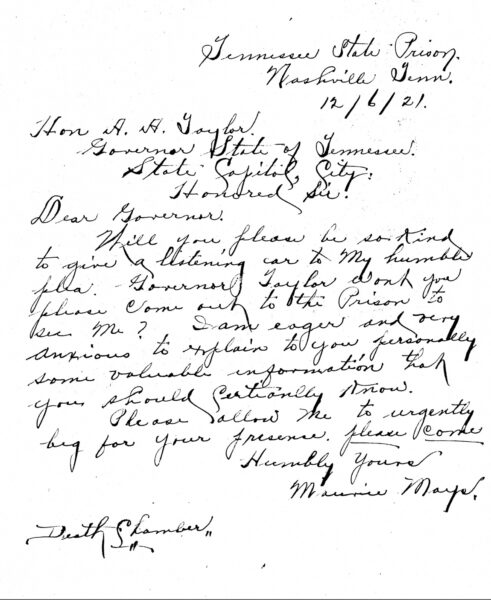

Even though I barely had time to absorb the material some days, it affected me. Working in Knoxville’s McClung Historical Collection, I became enthralled by the story of Maurice Mays. In August 1919, Mays was arrested on suspicion of murdering a white woman named Bertie Lindsay. A white lynch mob of 5,000 stormed the jail, dynamiting the building to get to Mays. Not finding their man, they proceeded to the African American section of town, looting stores, destroying property, and inciting a bloody race riot. Going through all of the Knoxville material chronologically, it became obvious that Mays was likely innocent: witness identification was hazy and prejudiced at best, and similar attacks continued after his jailing. Despite mounting evidence of his innocence, Mays was sentenced to death. In his death row letter to Tennessee Governor A. A. Taylor, Mays pleaded for assistance regarding his case.

A Wikipedia page, or a direct quote in a scholarly text, will never have the same impact as accessing Mays’ actual letter. Providing a breadth of material and viewpoints about what happened was important to me, so that people could learn about the complexity of the events that unfolded that summer, which included not just riots and lynchings, but forced expulsions of entire black populations of small towns, the destruction of black homes and businesses by white mobs in cities across America, and an increasingly militarized police, often protecting the wrong side. I’ve added to the archive newspaper articles, telegrams, photographs, court testimonies, inmate records, personal letters, NAACP and Urban League memos and minutes, and coroners’ reports.

Initially for my own benefit, I tracked the dates, locations, and types of violent events on a spreadsheet. As the summer progressed, I added columns for data like number of deaths or motivating factors. In the months after I returned home, with (at the time) minimal digital humanities skills, I built a website with a filterable archive of over 700 documents, an interactive map that allows users to compare all riots that took place that summer, and a timeline of events. The materials provide a comprehensive picture of what happened, and I’m still working to find additional material about smaller riots that barely registered in historical records.

There is a term in urban geography called “tactical urbanism” in which communities devise low-capital, often short-term solutions to challenges that can be executed outside of normal institutional channels. This includes things like filling potholes with plants, or creating rogue bike lanes. I consider Visualizing the Red Summer to be something like that: it was created on the fly; I wasn’t thinking about Dublin Core metadata standards that librarians and digital archivists use to link material; some of my photos are crooked or blurry or show up twice. I can’t say the site will be around forever, but it serves a function and meets a current need. I tried as much as possible to only include items likely free from restrictions, a task made easier by the fact that the events occurred before 1923.

My act of “tactical history” has provided tens of thousands of users with access to information that is otherwise disjointed and hidden. Had I pursued traditional routes for building this archive, filled with months of planning, grant cycles, fruitless meetings, and confusing conversations with tech folks, the process could have taken significantly more time and money. Going at it my own way allowed me to fill a need, faster, for nothing more than gas money, WordPress hosting and domain fees, and far too many meat-and-three dinners. With the centennial in 2019, institutions across the country like the Newberry Library are using Visualizing the Red Summer to discuss parallels between 1919 and today. The Newberry is holding a series of talks and events throughout the year to examine the legacy of the events that summer in Chicago. For something created out of impulse, the site has evolved into something far more than I had ever imagined, and has forced me to envision other ways public historians as well as scholars can make an impact with outside the box, tactical methods.

Karen Sieber currently works as the research and outreach coordinator for the Theodore Roosevelt Center and Digital Library. As a curator, her work includes Digital Loray, named a National Humanities Alliance “Humanities for All” site, as well as the Museum of Durham History’s H is for Hayti. Her current research includes travelling colleges of the 1920s and 1930s, and a project mapping Hobohemia. More at https://ksieber.com

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.