It would be impossible to summarize all the events that took place in New York City the first weekend of January at the AHA’s 134th annual meeting. From panels to plenaries to receptions, we can only provide a short flyover of a few of the weekend’s events. We hope you enjoy this sampler.

The registration and info desks at the Hilton stayed busy throughout the weekend.

Hands-On History

At “History for Young Audiences,” helping children to see themselves in the past was the theme of the day. Whether that is having students dress up as theologians, as Sean Gilmartin has; developing American Girl novels for an ever-more-diverse readership (including boys!), as Tessa Croker does; or finding ways to get students to see themselves in a museum exhibit, as Joanna Steinberg must, the audience of adults, children, and even a Samantha doll came away with a sense of the way many educators are approaching history education creatively in the 21st century.

One attendee poses with her American Girl dolls, Elizabeth and Blair.

Engaging today’s youth and convincing them of the significance of history is a challenging endeavor. Patrick Riccards offered data from the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation’s recent national survey of high school students, which found that students saw history as the second-least-interesting subject and the second-least-relevant subject (after the arts) to their futures. These data have pushed Riccards and his colleagues to consider new methods to make American history more interesting and relevant. A focus on social media, and how young people use it, is one important area of study, Riccards said.

High school teachers face these questions every day. Sean Gilmartin (Achievement First) has used techniques such as project-based learning, museum visits, and historical performances to help his students connect with the past. But, like Riccards, he has found that educators have to meet students where they are. Rather than showing entire documentaries, Gilmartin intersperses shorter film clips with class discussion, an easier way for young people to understand and digest course material when they are accustomed to watching short YouTube videos.

At American Girl, “We talk a lot about how we can hide vitamins in the chocolate cake,” says Croker.

Museums must interest visitors of all ages. So Joanna Steinberg (Museum of the City of New York) has to ask, “Is it possible for five- and six-year-olds to comprehend an exhibit on New York City labor activism?” It turns out that kindergarteners are experts on right and wrong, and they quickly understand why labor movements fight for better pay and working conditions. Steinberg noted that role-playing is one way to engage kids at the museum. By placing themselves in the shoes of people in the past—such as reenacting photos of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. leading a march or standing on a soapbox to discuss a topic of great importance to them—young visitors more easily see the importance of these events and understand the lives of those involved in social movements.

Tessa Croker (American Girl) said that the doll and publishing company thinks a lot about how to get historical messages into kids’ fun: “We talk a lot about how we can hide vitamins in the chocolate cake. At American Girl, we believe we can tell challenging stories to young children. How can I distill history to what an eight-year-old child can understand?” Cathy Gorn (National History Day) knows that children can handle those complicated subjects and that finding a good entry point is important for keeping them engaged. NHD students are often most interested in individuals and their lives. Through active learning—picking a topic, researching, taking notes, visiting archives and historical sites—NHD competitors learn how to tell a story and make an argument about the past through those individuals.

Across such varied experiences, the panel made it clear: getting kids interested in history means meeting them where they are. Whether using social media, tying the past to current events, or visiting places where history happened, kids will latch on and find something to be excited about. You just have to guide them there.

—LA

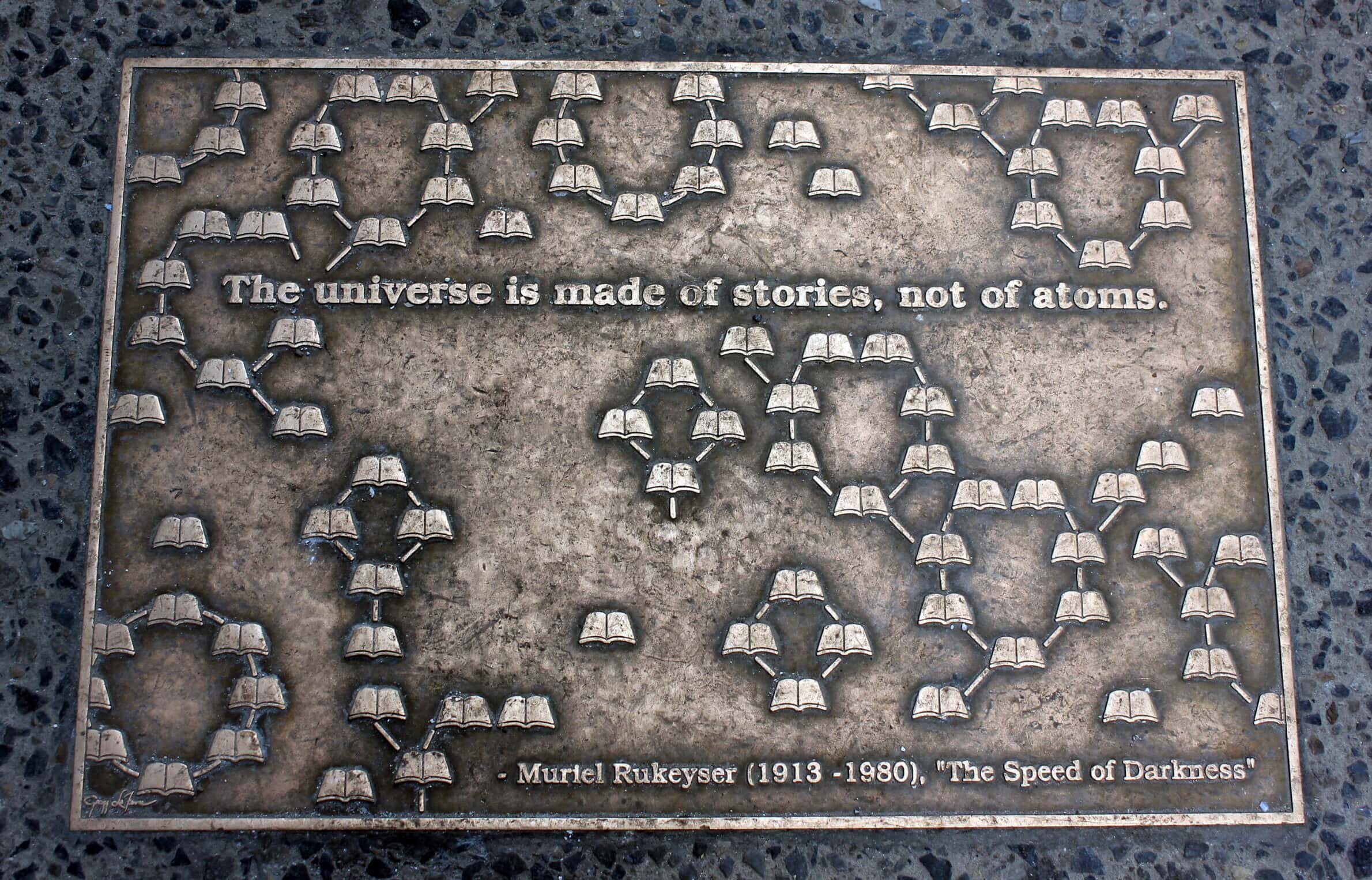

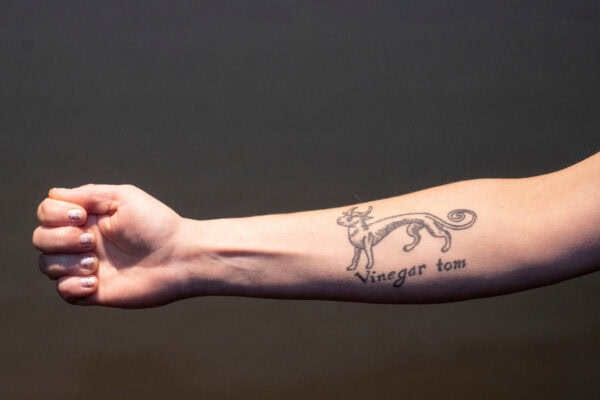

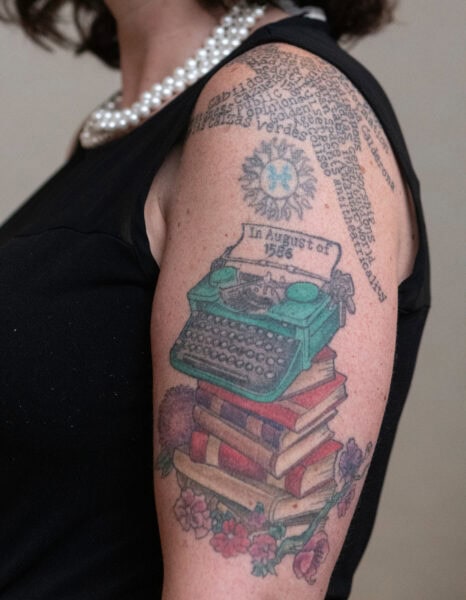

Inked on the Body

Historians don’t just ink historical facts onto book pages. Many have tattoos commemorating major events in their historical practice, from what first got them interested in history to books they themselves wrote. Attendees at the Reception for History Bloggers and #Twitterstorians shared their tats with Perspectives.

Amira Rose Davis

Amber Nickell

Lashona Slaughter Wilson

Ray Ball

Kevin Gannon

—EM

History in the Headlines

At recent meetings, late-breaking sessions, intended to make space on the meeting program for issues and controversies that occur after the February proposal deadline, have covered recent developments in Catalonian independence, the North Korean nuclear crisis, and Elizabeth Warren’s claims of Native ancestry. In 2020, we held the first late-breaking plenary. Convening experts on the presidency, Congress, and the courts, “Constitutional Separation of Powers: Why the Past Matters” addressed the Trump administration, impeachment, and even President Trump’s declaration that very day that his tweets should serve as sufficient communication with Congress.

Jeremi Suri, Maggie Blackhawk, Julian Zelizer, Annette Gordon-Reed, and Akhil Reed Amar at the Late-Breaking Plenary.

Gordon-Reed pointed to the many echoes of slavery that affect our politics and government today, whereas for Maggie Blackhawk (Univ. of Pennsylvania), Native histories are key to understanding the foundations of today’s political moment. Many battles over the separation of powers were fought during the period of Indian removal, westward expansion, and manifest destiny. In conquering a continental empire starting in the 1830s and 40s, the federal government set legal precedent for issues that still plague the United States today, such as executive war powers without a congressional declaration and unlimited plenary executive powers. Near constant wars with Native nations preceded today’s decades of war in the 21st-century Middle East; the reservation system was legal precedent for, first, Japanese internment during World War II and, now, detention of immigrants at the Mexican border.

Historians must interrogate whether these precedents from the past would be good practice today.

In contrast, congressional historian Julian Zelizer (Princeton Univ.) argued that the expansion of executive power was the central theme of the 20th century. Focusing on congressional history inevitably leads you to “find those moments where there are clashes between the branches,” bringing that delicate balance of power to the forefront of the story. Amar and Gordon-Reed discussed how the massive powers that the 20th-century military-industrial complex brought to the presidency has altered people’s view of the role. It used to take time to ramp up to war; now the United States has a massive standing army posted all over the globe. “When someone has the capacity to destroy the earth or wreak incredible havoc over the world, then people feel that the leader should have the power to make those decisions,” Gordon-Reed says. “People accept what they wouldn’t have before.”

But what about when one branch goes too far? Impeachment was clearly on the panel’s mind as they discussed oversight of the executive. Zelizer underscored how Congress’s power often comes down to the purse strings, and that they remain essential to the president’s legislative agenda. And they can make noise, as Democrats did in starting to reverse Iraq policy late in the George W. Bush administration and as the Tea Party did under Obama.

Each panelist had a view of the contemporary significance of these histories. Blackhawk argued that historians must interrogate whether these precedents from the past would be good practice today. We need to have a conversation about why laws employed to create Native reservations and Japanese internment camps are being cited to justify policies today. To Amar, knowing about this history is essential to being an informed voter. As Suri closed the plenary, “The history of the separation of powers shows that institutional history matters, and that the balance between institutions is significant,” an important takeaway in a presidential election year.

—LA

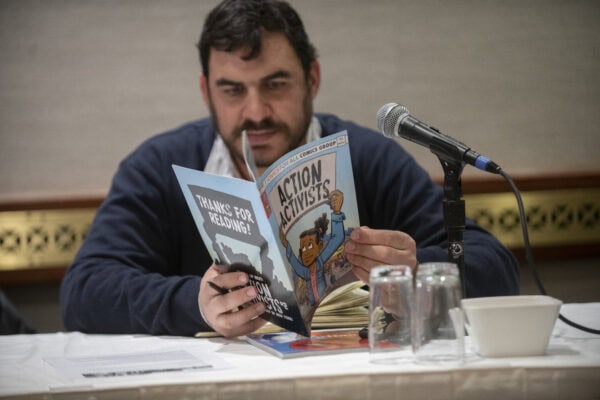

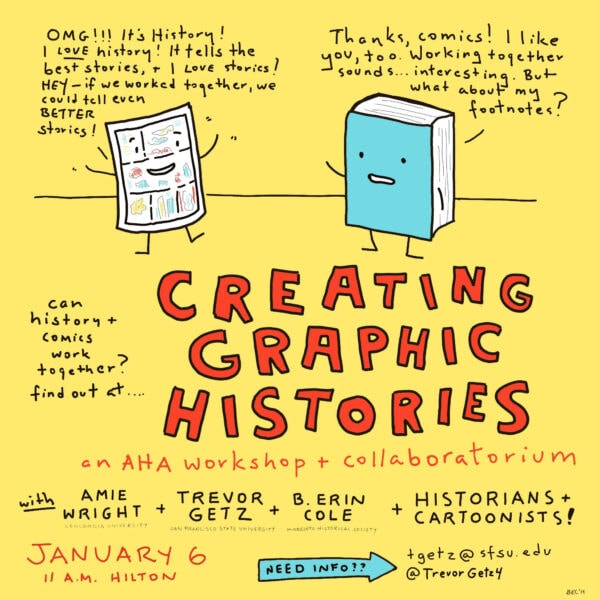

Comics in the Classroom

“Creating Graphic Histories” made it worth sticking around the meeting until the very end. The panelists, who all wear multiple hats—public historian and librarian, social studies teacher and comics advocate, historian and graphic history author, museum exhibit developer and cartoonist, and writer and illustrator of history books—came together to ask, “How do you do good history and good comics at the same time?” They covered a lot of ground in 90 minutes, exploring how to find comics for classroom use, techniques for teaching with comics, and how to go about turning your own research into graphic nonfiction.

Trevor Getz flips through a comic.

While working at the New York Public Library, Amie Wright (Concordia Univ.) teamed up with Joe Schmidt (NYC Dept. of Education) to bring comics and graphic formats into the classroom. New York City was the first large school district in the United States to adopt March, Congressman John Lewis’s graphic memoir, in the curriculum. Now the second-most-read nonfiction graphic text in US schools, its success has been a factor in the recent growth of nonfiction comics. Wright offered suggestions for publishers, as well as hashtags and websites where you can start looking for good comics, including the new “Graphic History Reviews” published in the AHR.

How do you do good history and good comics at the same time?

Trevor Getz (San Francisco State Univ.), author of Abina and the Important Men (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011), is a longtime comics lover. As he reminded the audience, writing a book in this format must be a true partnership with an artist. “Historians must abandon the idea that all the explanatory work will be done in the text,” he explained. Artist Liz Clarke pushed him to research new areas that would never have been necessary in a typical monograph. What did people wear? How close would they have stood to one another? Were there sewers along the streets? These kinds of questions—and not just what happened there—were essential when thinking about how the setting would have looked.

In her day job, B. Erin Cole develops museum exhibits at the Minnesota Historical Society. But she also is a cartoonist, drawing comics about her life and work as an urban historian. Both Cole and writer/illustrator Aubrey Nolan discussed the choices artists must make in translating a story into images. How do you decide on black-and-white images versus color? In Cole’s ongoing project about traumatic brain injury, only the main character appears in color (pink) for greater impact. Can archival material be incorporated into the text? For an upcoming anthology on woman suffrage, Nolan worked from archival photos to help create a comic on Elizabeth Cady Stanton, balancing inspiration from those images with her own style. The use of purple and yellow as the main colors was dictated by the suffrage movement’s own color choices.

Erin Cole promoted the “Creating Graphic Histories” session with her own artwork. B. Erin Cole

—LA

On to Seattle

2019 AHA president John R. McNeill speaks at the awards ceremony.

Photographs by Marc Monaghan (unless otherwise noted)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.