Editor’s Note: This article includes detailed descriptions of hate crimes.

On August 25, an AHA webinar, History Behind the Headlines: African American History and State Standards in Florida and Beyond, provided context for Florida’s new state standards for K–12 history and social studies education, which historians have widely criticized for their presentation of African American history. The event gathered four historians with experience in advocating for accurate and thorough inclusion of African American history in K–12 classrooms: Edward Ayers (Univ. of Richmond), Daina Ramey Berry (Univ. of California, Santa Barbara), Marvin Dunn (Florida International Univ.), and moderator Leslie Harris (Northwestern Univ.). The conversation ranged from how teachers use (and work around) state standards to what are age-appropriate ways to teach histories of racism and slavery to the role of historians in ensuring that honest history is taught to our nation’s schoolchildren.

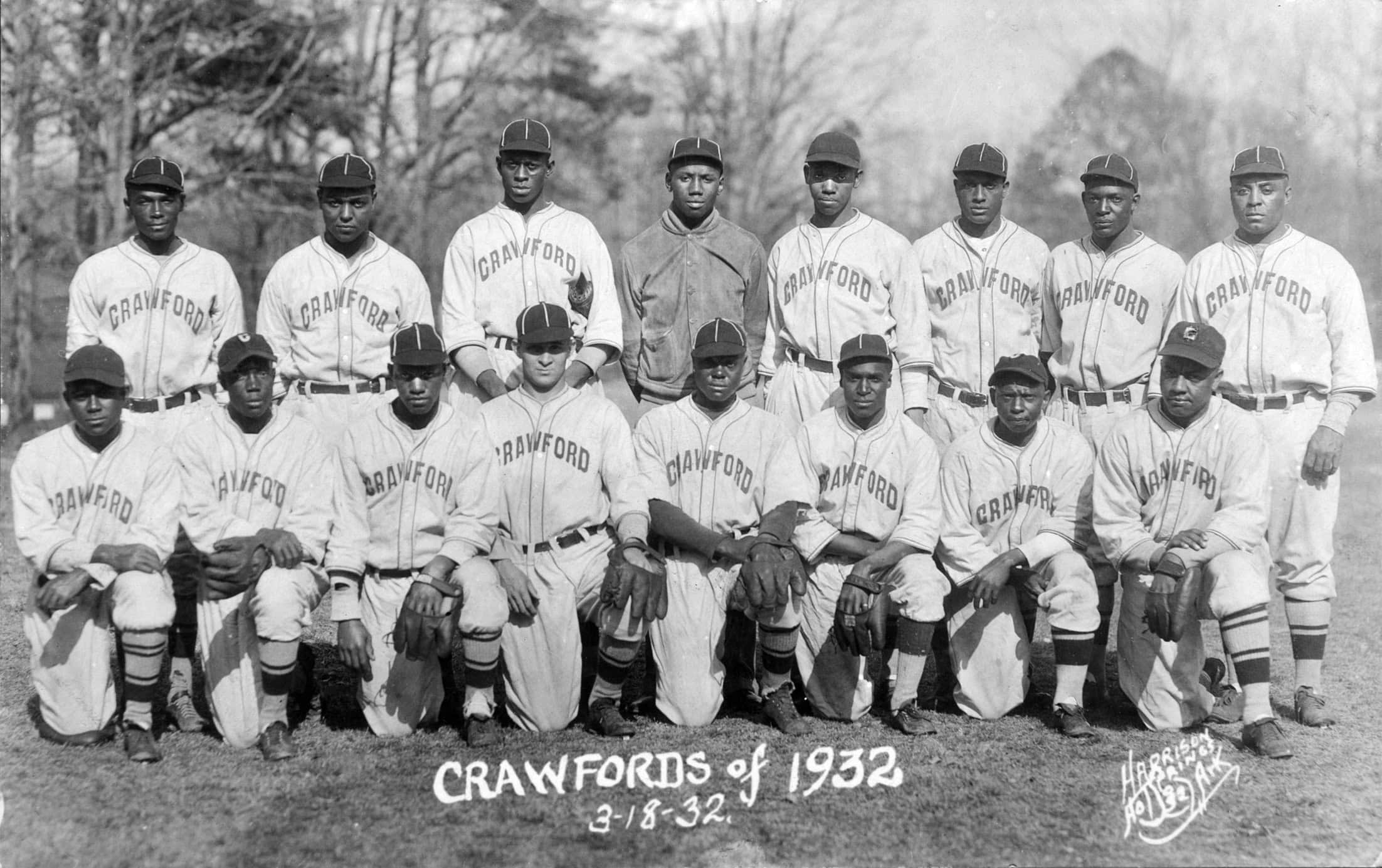

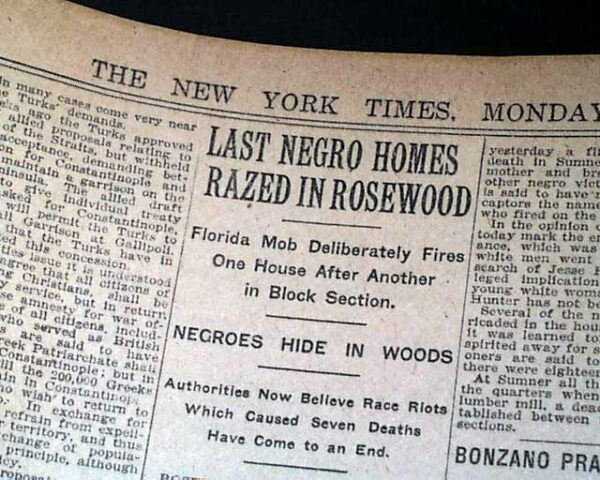

In Florida, histories of racist violence like the 1923 Rosewood massacre might not be covered in history classrooms. Wikimedia Commons/public domain

Harris began by asking the panelists to discuss their experiences with resistance to the inclusion of African American history in the broader narrative of the US past, and the audience heard an important reminder that racist violence is not merely an artifact of the past. Having spent years researching the 1923 Rosewood massacre, in which white Floridians destroyed a Black community, Dunn bought a parcel of land in Rosewood in 2008, making him the only Black person to own land there today. In September 2022, Dunn was visiting the land with six other men (four Black, two white) to discuss clearing the property. A white neighbor drove up and asked what was happening and why they were parked there. Dunn began to explain, and the man cut him off, went into a rage yelling racial epithets, and eventually tried to run them down with his pickup truck. Dunn called the police and the man was arrested; Dunn also called the FBI to report a hate crime. The man was charged under federal hate crime laws and convicted on all six counts; he now awaits trial on a state charge of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. When Dunn takes visitors to his property, which he plans to make a public history site, he now hires a police officer to provide security. Dunn remains dedicated to telling the story of Rosewood and building a peace house on his land to commemorate the massacre.

Ayers said his experience participating in recent curriculum development in Virginia was “the opposite of the story you just heard”—the standards fight was a long bureaucratic process, “but the consequences were meaningful.” In 2020, Ayers served on the Virginia Commission on African American History Education, which suggested a series of improvements to enrich the state’s educational standards in history and social studies. Over the next two years, Ayers and colleagues from across the state continued to advise the Virginia Department of Education as it undertook a thorough review of social studies curricula and developed a new set of K–12 standards. The state superintendent of public instruction and members of the state Board of Education appointed by the newly elected governor, Glenn Youngkin, rejected the resulting document and attempted to replace it with standards developed outside prescribed procedures and channels. Teachers, historians, parents, and organizations including the AHA mobilized in protest. According to Ayers, participation such as op-eds, expert testimony, and public turnout at Board of Education meetings all mattered in securing the future of history education in the state. “We used the tools of democracy,” he said, and “as a result, the frameworks were better.” Yet there were losses too—of the inquiry-based learning that pedagogical experts worked hard to weave throughout the original new standards; of relationships that became strained; and of “a public democratic process [that] was replaced by one of secrecy,” a precedent Ayers expects to outlive the current governor’s term—and that the AHA is beginning to see in other states.

Since the 1990s, Berry has participated in advocacy for K–12 history education. As a graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles, Berry witnessed firsthand historian Gary B. Nash’s leadership in creating comprehensive national history standards funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), only to find this team’s work denounced by NEH chair Lynne Cheney and then rejected in 1995 by the US Senate by a vote of 99–1. While a faculty member at the University of Texas at Austin, Berry joined with her colleagues in speaking before both state and local boards of education. When Texas piloted an ethnic studies program in high schools, history faculty spoke to the “value of learning about all key players in American history,” which students in the program verified in their own testimony. Yet Berry had to testify with a white man standing behind her, holding a giant Confederate flag while she and her colleagues spoke. Despite such experiences, UT faculty members remain dedicated to advocating for better social studies education, working with groups like Humanities Texas to help educators meet state standards while continuing to tell stories of the diverse people who shaped our history.

The audience heard an important reminder that racist violence is not merely an artifact of the past.

Formally, standards are requirements that teachers must meet in their classrooms; actual practices vary widely across states, depending in part on testing. But standards, Berry emphasized, usually cannot prevent educators from including additional content to broaden the narrative. So when they can, teachers often look for other stories and examples to add. Sometimes they do this quite creatively—in an English class, a requirement to learn about poetry might be met with poems by migrant workers, while others might choose to use slave narratives to teach autobiography. But as Ayers pointed out, “That’s exactly what’s at risk right now, because people are paying close attention to what is happening in the schools. Anything that deviates from standards is now seen as a violation of a gubernatorial edict.” In Virginia, he’s heard the most concern from teachers in rural areas, who feel that they must stick closely to the state documents. For these teachers, the standards are limiting, not empowering.

One of the major limitations in the new Florida standards seems to derive from what is deemed “age appropriate” in teaching difficult histories to students; the new standards leave out slavery until the 5th grade. Harris asked, “How can young students engage with race and racism effectively?” Ayers and Dunn both pointed to public history. At the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Ayers has seen the impact and power of their ability to teach younger audiences. Dunn often works with school groups and pointed to the value of experiential learning to their education. When he brings students to Rosewood, they all take photos and videos to post online, spreading the message even further. But as Berry reminded us, not all museums and historical societies are equal in this regard, with many less-resourced institutions needing to update their messages around topics like Indigenous and African American history. Docent training also is incredibly important to ensure that students are learning updated information.

But the children themselves are ready to learn about race well before 5th grade, Berry said. It’s all about the storytelling and the examples you use. She recommends focusing on stories of children of the same age in the past. If you teach them about the Little Rock Nine, Frederick Douglass’s childhood, or Anne Frank, “we can have these conversations and they can be age appropriate.” Dunn marveled at one child, a teacher’s nine-year-old daughter who attended a house tour with her parent’s high school students. In a house he had visited many times, she found a new room that he had never seen. As Harris said, “They can see this at their level and see things we don’t see.” “The good and bad have to go together to make any sense at all,” Ayers concluded. They are “hollow lessons” if children are taught about heroes like Harriet Tubman without learning what she was escaping or Rosa Parks without knowing what she was protesting.

Conversations about age appropriateness raised questions about the role of parents in curriculum controversies. In Florida, where a single parent’s objections can take a book off school shelves, Dunn argued that Governor Ron DeSantis has overemphasized what has come to be referred to as “parental rights.” The problem, as Ayers wryly observed, is that parental involvement through groups like PTAs “has been around for a long time.” Now social media has empowered people as individuals. We must remember, Ayers cautioned, that “everyone has a voice, but everyone has to listen to everyone else’s voices.” Parental involvement can cut both ways—while some parents are challenging books that engage so-called “divisive concepts,” Berry also worked on a textbook revision that resulted from a parent objecting to its depiction of enslaved people as immigrants.

There’s plenty of other good work happening in this moment of increased division over public education. Harris pointed out how book bans lead both children and adults to become more curious and read those challenged books. Ayers’s personal experience as a white Southerner who attended Andrew Johnson Elementary School before integration gives him some hope. He sees this moment as a backlash, “an effort to contain something that I don’t think can be contained, which is a democratization of American history.” Today’s fights are, he said, “a rear-guard action” responding to progress over the last three generations. It’s taken a long time, but “to equip ourselves to proceed, you need to remember what has been won so far.”

Children themselves are ready to learn about race well before 5th grade.

What can historians do? Dunn asked academic historians to disseminate their work to the public and online as much as they can. Berry agreed, saying, “If we’re not a part of these conversations, we’re not going to be able to right the wrongs in these books that people are learning.” As public-engaged scholarship becomes more popular, she has been pushing for academic institutions to count these projects in tenure and promotion, a call echoed in the AHA’s recent Guidelines for Broadening the Definition of Historical Scholarship.

Ayers capped the day with an important reminder for all historians: “We should listen more and talk less with our teacher colleagues. How can I be of use? What do you want to know? What would be helpful?” As Florida and other states continue to rewrite history and social studies public education, these questions will remain essential for those of us who want to promote the teaching of honest history.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.