A 16th-century Mughal miniature will likely be sold for 8,000–10,000 British pounds at Christie’s Islamic art auction on October 8. In a phone interview, Andrew Butler-Wheelhouse, specialist in Islamic and Indian art at Christie’s King Street, described this unique miniature, which was originally made in India.

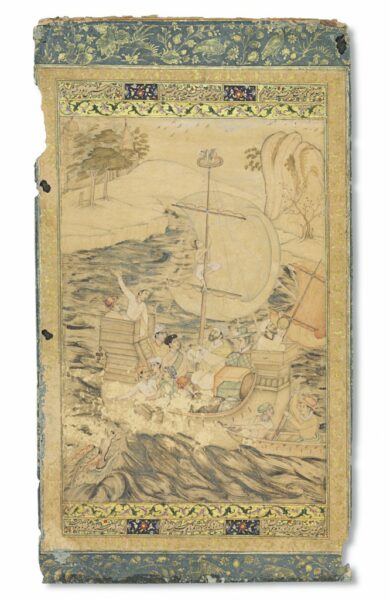

Combining different cultural influences and borrowings, it traveled to Iran soon after it was made, and once there, borders were made around it in the Safavid period (1501–1736). Eventually, the miniature made its way to Europe in the late 19th century. The miniature portrays a ship on a black body of water. Originally, the water was not black; the pigment, made of silver, oxidized over time, and turned black. The silvery water “would have given you the impression that this would have been nighttime or dusk,” Butler-Wheelhouse said, which would explain the use of the astrolabe, a nautical device that requires the ability to see the stars (note the figure in the front of the boat).

Butler-Wheelhouse pointed out the different ethnicities of the people on the merchant ship. “There are figures in European costume. They’re the ones with bowler-hat style headgear on. There’s one in an orange hat in the back and a few in the middle to the side of the boat, and one in a high green hat near the front. It’s a typical Mughal way of representing Portuguese traders. If you look at the hats themselves, they are quite high on the head. The artist might not have seen people wearing this kind of hat. They might have seen images only,” Butler-Wheelhouse explained. He also pointed out another European element in the image—“a European-made musket being loaded in the lower right corner.”

Butler-Wheelhouse pointed out the different ethnicities of the people on the merchant ship. “There are figures in European costume. They’re the ones with bowler-hat style headgear on. There’s one in an orange hat in the back and a few in the middle to the side of the boat, and one in a high green hat near the front. It’s a typical Mughal way of representing Portuguese traders. If you look at the hats themselves, they are quite high on the head. The artist might not have seen people wearing this kind of hat. They might have seen images only,” Butler-Wheelhouse explained. He also pointed out another European element in the image—“a European-made musket being loaded in the lower right corner.”

The other figures on the ship come from different backgrounds as well. “The guy with his hand outstretched [left],” according to Butler-Wheelhouse, “is wearing a Mughal turban in Akbar-era style,” while the bearded figure in the turban [right] is either Arab or Iranian. (The Mughal emperor Akbar ruled from 1556 to 1605.) “It’s more likely to be an Iranian, but in terms of the design of the turban it can be either. It could be someone from the Persian Gulf.

The other figures on the ship come from different backgrounds as well. “The guy with his hand outstretched [left],” according to Butler-Wheelhouse, “is wearing a Mughal turban in Akbar-era style,” while the bearded figure in the turban [right] is either Arab or Iranian. (The Mughal emperor Akbar ruled from 1556 to 1605.) “It’s more likely to be an Iranian, but in terms of the design of the turban it can be either. It could be someone from the Persian Gulf.

Reflecting on the group represented, he continued, “That’s a very mixed crew on this one ship. I wouldn’t have thought that it would have been common for people of so many different ethnicities to be on the same boat. The Portuguese would have had one or two people who would’ve been local guiding them, but they were, generally speaking, not overly tolerant of Muslims. They also have an antagonistic relationship unless they were dealing with a major power that they wanted to trade with. They didn’t take other people with them.”

“What’s interesting as well is a figure looking at an orb that’s some kind of an astrolabe or an astrological globe. It’s not clear if it’s for navigation purposes or divination. It’s probably an astrolabe and he’s taking some kind of reading to pinpoint their location. It’s not often we see people actually using instruments in miniatures. You can also see by the form of the boat that it’s a European boat. It’s interesting to see an astrolabe that originated in the Arab world on a European trading ship.” Note the wares at the front of the boat.

“What’s interesting as well is a figure looking at an orb that’s some kind of an astrolabe or an astrological globe. It’s not clear if it’s for navigation purposes or divination. It’s probably an astrolabe and he’s taking some kind of reading to pinpoint their location. It’s not often we see people actually using instruments in miniatures. You can also see by the form of the boat that it’s a European boat. It’s interesting to see an astrolabe that originated in the Arab world on a European trading ship.” Note the wares at the front of the boat.

The artist includes other interesting nautical details. “The guy at the top is a scout. He would look for land, plot the course of the ship, and look for obstacles. He’s adding to the drama of the scene. He’s showing that the major danger is the monster next to the ship and not anything further afield. He’s looking down at that. If you see Renaissance maps, they often feature imaginary monsters. It’s part of the whole mystique of exploration.”

The artist includes other interesting nautical details. “The guy at the top is a scout. He would look for land, plot the course of the ship, and look for obstacles. He’s adding to the drama of the scene. He’s showing that the major danger is the monster next to the ship and not anything further afield. He’s looking down at that. If you see Renaissance maps, they often feature imaginary monsters. It’s part of the whole mystique of exploration.”

Finally, Butler-Wheelhouse pointed out how the artist incorporates his own unique culture in the miniature: “But then there are certain local Indian touches to the boat itself. If you look at the back of the boat, there are two rounded objects and something that looks like an umbrella. It’s an adaptation of an Indian charm that, if you go to India today, you will see people using. Good luck charms hang on taxis and in buses and other modes of transport. Generally these days, they use a lime and a green chili tied together on a string …The artist is adding his own influence to the miniature.”

Finally, Butler-Wheelhouse pointed out how the artist incorporates his own unique culture in the miniature: “But then there are certain local Indian touches to the boat itself. If you look at the back of the boat, there are two rounded objects and something that looks like an umbrella. It’s an adaptation of an Indian charm that, if you go to India today, you will see people using. Good luck charms hang on taxis and in buses and other modes of transport. Generally these days, they use a lime and a green chili tied together on a string …The artist is adding his own influence to the miniature.”

Mughal miniatures usually portray Mughal sultans and sometimes religious figures. As European merchants traveled to India in the 16th and 17th centuries, however, they brought with them European art, and Indian artists began featuring European subjects in their work. For example, another Mughal miniature in the October 8 auction portrays King James I, who ruled England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1603 until his death in 1625. The artist who made that miniature of King James I, Butler-Wheelhouse thinks, was inspired by a European painting, and so was the artist who made the miniature of the merchant ship above. Not having seen European merchant ships himself, however, the artist used his imagination to embellish the scene, combining Indian and European elements in unusual ways. To read about another Indian miniature that scholars think was inspired by a European engraving, read “A 17th-Century Indian Parrot: Interpreting the Art of the Deccan” in the Perspectives on History 2015 summer issue.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.