The following is a list of the recipients of the 2009 awards, prizes, and honors that were presented at the General Meeting of the American Historical Association on Friday, January 8, 2010, in the Elizabeth Ballroom F of the Manchester Grand Hyatt Hotel in San Diego, California.

Awards for Scholarly Distinction

In 1984 the Council of the American Historical Association established the American Historical Association Award for Scholarly Distinction. Each year a nominating jury, composed of the president, president-elect, and immediate past president, recommends to the Council of the Association up to three names for the award. Nominees are senior historians of the highest distinction in the historical profession who have spent the bulk of their professional careers in the United States. Previous awards have gone to Nettie Lee Benson, Woodrow Borah, Alfred D. Chandler Jr., Thomas D. Clark, David Brion Davis, Angie Debo, Martin Duberman, Helen G. Edmonds, Elizabeth Eisenstein, Lloyd Gardner, Peter Gay, Felix Gilbert, Jack P. Greene, John Whitney Hall, Tulio Halperín-Donghi, Joseph E. Harris, John Higham, H. Stuart Hughes, Margaret Atwood Judson, Michael Kammen, Nikkie R. Keddie, George F. Kennan, Paul Oskar Kristeller, Gerhart B. Ladner, Gerda Lerner, Lawrence W. Levine, Wallace T. MacCaffrey, Ramsay MacMullen, Ernest R. May, Arno J. Mayer, Richard P. McCormick, August Meier, Edmund Morgan, George L. Mosse, Robert O. Paxton, John G. A. Pocock, Earl Pomeroy, H. Leon Prather Sr., Benjamin Quarles, Edwin O. Reischauer, Robert V. Remini, Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, Caroline Robbins, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Carl E. Schorske, Anne Firor Scott, Joan Wallach Scott, Benjamin I. Schwartz, Kenneth M. Setton, Nancy G. Siraisi, Kenneth M. Stampp, Chester G. Starr, Barbara and Stanley Stein, Fritz Stern, Lawrence Stone, Sylvia L. Thrupp Strayer, Merze Tate, Emma Lou Thornbrough, Brian Tierney, David Underdown, Eugen Weber, Gerhard Weinberg, and George R. Woolfolk.

Joining this distinguished list are Leon Litwack (UCLA) and Saul Friedländer (University of California, Los Angeles).

Over the past half century, Saul Friedländer, professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles, has become one of the most influential historians in the world working on Nazi Germany, World War II, and the persecution and then extermination of European Jewry. In many works, fromPrelude to Downfall: Hitler and the United States, 1939–1941 (French, 1963, English, 1967) to his masterful two-volume work, Nazi Germany and the Jews, Vol. I, The Years of Persecution, andVol. II, The Years of Extermination (1997 and 2007; abridged edition, 2009), he has been a leader in the American and international historical profession’s effort to incorporate the history of the Holocaust into the main narrative of Nazi Germany and Europe during before and during World War II. His “integrated history” of the Holocaust powerfully integrated evidence from the official documents of the Nazi regime with that offered by Jewish diarists.

He has been a member of the international and American historical profession. Before coming to UCLA in 1987, he taught at the University of Geneva (1963–67, 1967–87), the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (1969–75), and the University of Tel Aviv (1976–87). His publications include studies of the Catholic Church during the Holocaust and of the motivations of Nazi perpetrators. He reached a general audience with When Memory Comes, his powerful memoir of survival as a boy hidden in a Roman Catholic seminary in France during the Holocaust followed by his eventual awareness of his Jewish origins and coming of age in Israel. A decade later, Friedländer co-founded the influential journal, History and Memory.

At UCLA, Saul Friedländer has been a fine teacher and mentor to an impressive group of American doctoral students as well as a highly regarded lecturer to undergraduates.

Among his many honors, in 2000 Friedlander was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 2008, The Years of Extermination was awarded the general non-fiction Pulitzer Prize. Historians around the world working on Nazi Germany and the Jews will be drawing on his body of work for many years to come. It is fully appropriate that Saul Friedländer receive the AHA’s Award for Scholarly Distinction.

Leon Litwack’s work has transformed the way we think about U.S. history. Elegantly crafted, engagingly written, and bitingly cogent, his writings have reshaped our understanding of the course of African American history and of the Civil War era and have shifted our understanding of social relations in our own time.

Litwack’ first book, North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790–1860 (1961), was a major turning point in the development of the burgeoning field of what would soon come to be called black history. He demonstrated that the “free states” were infused with slavery and that the comforting bright line between slavery and freedom that characterized the narrative of U.S. history as then written simply did not exist.

Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (1979), which won the Pulitzer Prize for 1979, is now nearly thirty years old; its similarly magisterial successor, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (1998), has also made a large impact on Afro-American and American history. Litwack’s determination to see the emancipation experience from the point of view of documents produced by black people themselves, his pathbreaking focus on the complex transition from slave to free labor, his exploration of how independent black institutions such as schools and churches emerged from the ashes of slavery, and how black culture has been shaped and reshaped by segregation, disfranchisement, and eventually migration, remain an inspiration to a host of scholars, continuing to destabilize inherited knowledge and inspire current research.

He has long put energy into collaborative work that makes historical scholarship accessible to wide audiences; perhaps his most influential exercise in this regard isWithout Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (2000), a project that became a traveling museum exhibition, a book, and web site that publicized the shocking findings of research that many had preferred to ignore, and also helped many historians think creatively about how they might make the issues that shape their scholarly inquiries accessible to museum audiences. In his service as the general editor ofThe Harvard Guide to African-American History (2001) and as an adviser to Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years he has sustained reference and documentary editions. And he has energetically conveyed new scholarship to the public, notably in the legendary American history survey courses he taught throughout his career at Berkeley (at last count, it was estimated to a total of some 30,000 students over the years). In these lectures he merged the newest scholarship with other media photographs, music, and film in ways that are themselves scholarship at its best.

Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award

Established in 1986, the Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award recognizes outstanding teaching and advocacy for history teaching at two-year, four-year, and graduate colleges and universities, by commending an inspiring teacher whose pedagogical techniques and mastery of subject matter make a lasting impression and substantial difference to students of history. The prize is named for the late Eugene Asher who was for many years a leading advocate for history teaching. The Society for History Education (SHE) shares with the AHA sponsorship of the award. Members of the AHA and SHE submit nominations to the Committee on Teaching Prizes.

Established in 1986, the Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award recognizes outstanding teaching and advocacy for history teaching at two-year, four-year, and graduate colleges and universities, by commending an inspiring teacher whose pedagogical techniques and mastery of subject matter make a lasting impression and substantial difference to students of history. The prize is named for the late Eugene Asher who was for many years a leading advocate for history teaching. The Society for History Education (SHE) shares with the AHA sponsorship of the award. Members of the AHA and SHE submit nominations to the Committee on Teaching Prizes.

The 2009 honoree is Brad D. Lookingbill (Columbia Coll. of Missouri). The committee’s citation reads: “Brad Lookingbill believes that the study of history is best understood as a ‘journey of people’ and students who have accompanied him on this journey have found his passion left them, as one wrote, ‘fired-up’ to learn. Along with his commitment to enriching the classroom experience, Professor Lookingbill has also impressively served both his college and the outside community while maintaining an active research program that has led to numerous articles and two monographs.”

Beveridge Family Teaching Award

Established in 1995, this prize honors the Beveridge family’s long-standing commitment to the AHA and to K–12 teaching. Friends and family members endowed this award to recognize excellence and innovation in elementary, middle, and secondary school history teaching, including career contributions and specific initiatives. The individual can be recognized either for individual excellence in teaching or for an innovative initiative applicable to the entire field. It is offered on a two-cycle rotation: in even-numbered years, to an individual; in odd-numbered years, to a group. The prize was first offered in 1996, and in 2009 was awarded to a group of history teachers.

Established in 1995, this prize honors the Beveridge family’s long-standing commitment to the AHA and to K–12 teaching. Friends and family members endowed this award to recognize excellence and innovation in elementary, middle, and secondary school history teaching, including career contributions and specific initiatives. The individual can be recognized either for individual excellence in teaching or for an innovative initiative applicable to the entire field. It is offered on a two-cycle rotation: in even-numbered years, to an individual; in odd-numbered years, to a group. The prize was first offered in 1996, and in 2009 was awarded to a group of history teachers.

The 14th recipient of the Beveridge Family Teaching Prize is the Oral History Project at D.C. Everest High School in Weston, Wisconsin. Beginning in 1998 with interviews of newly arrived Hmong immigrants from Laos, the Social Studies Department at D.C. Everest High School has made their oral history project into a nationally recognized leader in the use of oral history in secondary schools. With a commitment to reaching out to their local community and particularly neglected groups like the Hmong, the project has also led to an impressive series of publications that currently consists of 15 books.

Extraordinary Service Award

At is June 2009 meeting, the Council of the American Historical Association unanimously agreed to present an Extraordinary Service Award to outgoing member Elise Lipkowitz (Univ. of Michigan).

At is June 2009 meeting, the Council of the American Historical Association unanimously agreed to present an Extraordinary Service Award to outgoing member Elise Lipkowitz (Univ. of Michigan).

Elise was elected to the Council in the fall of 2005, and served a three-year term beginning in January 2006. She agreed to serve ex officio a fourth year in 2009. Membership approval of a new AHA Constitution in January 2008 necessitated changes to the composition of the Council, which are being phased in during the 2008, 2009, and 2010 elections. Elise’s additional service was essential to ensure representation of graduate student issues on the Council.

As Council’s graduate student member, Elise served as chair of the Graduate and Early Career Committee (formerly the Committee for Graduate Students) and has provided remarkable leadership to the AHA. Among her many accomplishments, she conceptualized a section on the AHA’s web site beginning with graduate school and ending with early career professionals, dealing with topics such as Graduate School from Start to Finish and Preparing for the Job Market. More recently, she has worked on a section for early career professionals.

Elise conceptualized, organized, and edited the AHA pamphlet, From Concept to Completion: A Dissertation-Writing Guide for History Students, which in short order became the AHA’s bestselling pamphlet. To ensure that the annual meeting becomes a more rewarding experience for graduate students, she chaired and organized annual meeting sessions, chaired the annual forum for graduate students, prepared an orientation letter about the annual meeting for graduate students, helped organize a video on the Job Center for the AHA web site, and wrote the text for a poster encouraging graduate students to join the AHA. During her tenure on the Council, she commissioned forums for Perspectives on History such as “From Notes to Narrative” and served on the AHA Implementation Committee, a subcommittee of Council formed following the report of the Working Group on the Future of the AHA.

Herbert Feis Award for Distinguished Contributions to Public History

Established in 1984, this prize is offered annually to recognize distinguished contributions to public history during the previous ten years. The prize is named in memory of Herbert Feis (1893–1972), public servant and historian of recent American foreign policy, with an initial endowment from the Rockefeller Foundation. The prize was originally given for books produced by historians working outside of academe. From 2006, the scope of the award is widened to include other types of public history work.

The terms of the award now define both “contribution” and “public history” broadly. Contributions could, for example, include work as the administrator of a public history group or agency (such as a historical society, a historic site, or a community history project) or as the creator or producer of a public history product or products (such as a museum exhibit, radio script, web site, oral history collection, or film). Often, the contribution will be the result of years of effort in the field, but the prize can also recognize a singular contribution of major importance such as a pathbreaking museum exhibit. Public history is defined as work primarily directed at non-academic, non-school-based audiences. Those audiences could be very broad (e.g., television viewers) or highly specialized (e.g., policymakers). Although the audience is primarily outside of academia, the recipient of the award can be employed at a university.

The 2009 prize was awarded posthumously to Noel J. Stowe (Arizona State Univ.). Noel Stowe’s legacy of service to the profession at the local, state, and national levels helped shape the practice of public history. He was a founder of the National Council on Public History, introduced an MA program at Arizona State University, and was the author of five books and numerous articles. He bridged the gap between academia and cultural and historical institutions, serving on committees and boards of humanities councils, historical societies, and professional organizations.

William Gilbert Award for the Best Article on Teaching History

Named in memory of William Gilbert, a longtime AHA member and distinguished scholar-teacher at the University of Kansas, this biennial award recognizes outstanding contributions to the teaching of history through the publication of journal and serial articles. Eligible for consideration are articles written by members of the AHA and published in the United States during the previous two years. Journals, magazines, and other serials that publish works on the teaching of history, including methodology and theory of pedagogy, are also eligible to submit nominations.

Named in memory of William Gilbert, a longtime AHA member and distinguished scholar-teacher at the University of Kansas, this biennial award recognizes outstanding contributions to the teaching of history through the publication of journal and serial articles. Eligible for consideration are articles written by members of the AHA and published in the United States during the previous two years. Journals, magazines, and other serials that publish works on the teaching of history, including methodology and theory of pedagogy, are also eligible to submit nominations.

The seventh Gilbert Award is presented to Julia Clancy-Smith (Univ. of Arizona), for her article “An Undergraduate and Graduate Colloquium in Social History and Biography in the Modern Middle East and North Africa” in Teaching Life Writing Texts, Modern Language Association. For more than 20 years, Professor Julia Clancy-Smith has used close readings of life stories to introduce students to the issue of identities in the modern Middle East and North Africa. Besides tracing changes to her syllabi reflecting the expansion of materials available in postcolonial studies, Professor Clancy-Smith’s article shows the value of an interdisciplinary approach by making use of both literature and historical sources to challenge commonly held assumptions regarding individuals from these regions.

John E. O’Connor Film Award

In recognition of his exceptional role as a pioneer in both teaching and research regarding film and history, the American Historical Association established this award in honor of John E. O’Connor of the New Jersey Institute of Technology. The award seeks to recognize outstanding interpretations of history through the medium of film or video. Essential elements are stimulation of thought, imaginative use of the media, effective presentation of information and ideas, sensitivity to modern scholarship, and accuracy. The production should encourage viewers to ask questions about historical interpretations as well as make a contribution to the understanding of history.

In recognition of his exceptional role as a pioneer in both teaching and research regarding film and history, the American Historical Association established this award in honor of John E. O’Connor of the New Jersey Institute of Technology. The award seeks to recognize outstanding interpretations of history through the medium of film or video. Essential elements are stimulation of thought, imaginative use of the media, effective presentation of information and ideas, sensitivity to modern scholarship, and accuracy. The production should encourage viewers to ask questions about historical interpretations as well as make a contribution to the understanding of history.

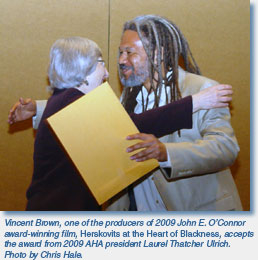

The 16th O’Connor Award was presented to Herskovits at the Heart of Blackness, producers: Llewellyn Smith, Vincent Brown, and Christine Herbes-Sommers, co-production of Vital Pictures and the Independent Television Service.

Herskovits at the Heart of Blackness is a thought-provoking documentary about Herskovits’s foundational contributions to anthropology, African American history, and cultural studies as well as the continuing intellectual relevance of his work. The authors have imaginatively combined archival film footage (some shot by Herskovits himself), photographs, animation, and re-enactments. The result is a highly effective use of the visual medium of film, especially in the fast-paced accumulation of profound questions at the end of the documentary and in the segment concerning the 1969 storming of the African Studies Association by black activists, which productively recalls Chris Marker’s seminal photo-essay, La Jetée.

Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award

In recognition of Nancy Lyman Roelker’s role as a teacher, scholar, and committee member of the historical profession, and on the occasion of her 75th birthday, friends, colleagues, and former students established the Nancy Lyman Roelker Mentorship Award. The annual award recognizes and encourages a special quality exemplified by Professor Roelker through the human component in her teaching of history.

Mentoring should encompass not only a belief in the value of the study of history but also a commitment to and a love of teaching it to students regardless of age or career goals. Advising is an essential component, but it also combines a consistent personal commitment by the mentor to the student as a person. Offering a human alternative, frequently in quiet and unacknowledged ways, mentors like Professor Roelker believe that the essence of history lies in its human scope. With this award, the American Historical Association attests to the special role of mentors to the future of the historical profession.

Mentoring should encompass not only a belief in the value of the study of history but also a commitment to and a love of teaching it to students regardless of age or career goals. Advising is an essential component, but it also combines a consistent personal commitment by the mentor to the student as a person. Offering a human alternative, frequently in quiet and unacknowledged ways, mentors like Professor Roelker believe that the essence of history lies in its human scope. With this award, the American Historical Association attests to the special role of mentors to the future of the historical profession.

The award is given on a three-cycle rotation to graduate, undergraduate, and secondary school teacher mentors. Nominations for the 2009 prize were for a graduate mentor. Lynn Hunt (UCLA) is the recipient of the 18th annual Roelker Mentorship Award.

A talented French historian, Lynn Hunt has dedicated the past 35 years to her craft. Her peers testify to her unstintingly generous dedication to research and teaching as well as to her exemplary mentoring of a diverse array of graduate students. Time and again in their letters of support, her graduate students, both past and present, referred to her willingness to dedicate her time and talents to facilitating their pursuit of excellence in academics and in life. As one of her students wrote: “In shaping us, she shaped a profession for years to come.”

Roy Rosenzweig Fellowship for Innovation in Digital History

The Roy Rosenzweig Fellowship for Innovation in Digital History is sponsored jointly by the AHA and the Center for History and New Media (CHNM) at George Mason University. This nonresidential fellowship is awarded annually to honor and support work on an innovative and freely available new media project, and in particular for work that reflects thoughtful, critical, and rigorous engagement with technology and the practice of history. The fellowship is conferred on a project that is either in a late stage of development or which has been launched in the past year but is still in need of further improvements. Committee members representing the AHA and George Mason University are Daniel Cohen, George Mason University, chair; Stephen Brier, Graduate Center, City University of New York; Michael O’Malley, George Mason University; Jan Reiff, University of California, Los Angeles; and Stefan Tanaka, University of California, San Diego.

The 2009 fellowship was awarded to Digital Harlem: Everyday Life, 1915–1930, Stephen Robertson, Shane White, Stephen Garton, and Graham White, University of Sydney.

Digital Harlem: Everyday Life, 1915–1930 presents the social history of a particular time and place in an elegant way that encourages exploration and new discoveries. The team behind the site draws on the strength of the primary sources and uses digital techniques to allow the viewer to see elements and patterns during the Harlem Renaissance that would be difficult to characterize in narrative. In addition to being open access, Digital Harlem is open-ended: researchers can explore themes of interest to them, layering experimental searches upon each other to envision the character and interactions of everyday life. The site also powerfully shows what can be done with the combination of common technology (Google Maps) with deep archival research and outstanding web design and functionality.

Honorary Foreign Member

At its second annual meeting in Saratoga in 1885, the newly appointed Committee on Nominations for Honorary Membership introduced a resolution, which was adopted, that appointed Leopold von Ranke as the first honorary foreign member. Previously selected biennially, selection is now made annually to honor a foreign scholar who is distinguished in his or her field and who has “notably aided the work of American historians.”

President-elect Metcalf announced the addition of Romila Thapar, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India to this roll of distinguished foreign scholar members, and read the following citation: “Professor Thapar is among India’s most distinguished historians. She is a meticulous scholar, a generous colleague, and a fierce public intellectual. Professor Thapar represents the very best in South Asian history and speaks to the wider concerns of our entire profession. An ancient historian by training and focus, she is the author or editor of twenty-three books, primarily on the early history of India. Professor Thapar’s History of India has been the book of choice for any introduction to the subject. If it has been supplanted in recent years, it is only by Professor Thapar’s own updated contribution, Early India. To put it simply, Professor Thapar’s work is the bedrock of all scholarly study of the early South Asian past.

“While this in itself is a remarkable achievement, Professor Thapar has also been at the forefront of any number of contemporary issues. Nowhere is this more apparent than in her role as the leading intellectual voice opposing the violent campaigns of right-wing Hindu nationalism, built on certain interpretations of history. Professor Thapar has been courageous in standing up for professional historical inquiry, and for taking the heat, even in the face of extreme threats and harassment. And as a professional colleague, she has been an extraordinary help to American scholars working in and on India. In all respects, she is a most worthy addition to the list of honorary foreign members.”

2009 Book Awards

Herbert Baxter Adams Prize

Priya Satia (Stanford Univ.) for Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural Foundations of Britain’s Covert Empire in the Middle East (Oxford University Press). Elegantly written and meticulously researched, Satia’s study of British intelligence agents during the first third of the twentieth century is a spectacular accomplishment. Drawing on a wide range of archival and literary sources, Satia reveals how the shared cultural notions of a small number of British agents shaped a new form of covert empire in the Middle East. The book’s integration of cultural, military, and political history provides remarkable insights into the dynamics of British imperialism.

George Louis Beer Prize

William I. Hitchcock (Temple Univ.) for The Bitter Road to Freedom: A New History of the Liberation of Europe (Free Press). This powerful narrative challenges the “good war” memory of the liberation of Europe. Its transnational and multi-leveled perspective captures the bittersweet experiences of both liberators and the liberated. This portrayal is innovative, since it represents the first comparison of liberation across the continent, including peoples occupied by the Nazis, Jewish Holocaust survivors, and ethnic Germans. Focused on a single transatlantic theme, the book is a model of how a truly European history might be written.

William I. Hitchcock (Temple Univ.) for The Bitter Road to Freedom: A New History of the Liberation of Europe (Free Press). This powerful narrative challenges the “good war” memory of the liberation of Europe. Its transnational and multi-leveled perspective captures the bittersweet experiences of both liberators and the liberated. This portrayal is innovative, since it represents the first comparison of liberation across the continent, including peoples occupied by the Nazis, Jewish Holocaust survivors, and ethnic Germans. Focused on a single transatlantic theme, the book is a model of how a truly European history might be written.

Albert J. Beveridge Award

Karl Jacoby (Brown Univ.) for Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History (Penguin Press). Jacoby has crafted a beautifully written book, notable for its questioning of historical narrative itself. His reappraisal of the 1871 Camp Grant massacre deeply historicizes violence in the borderlands. Using indigenous sources, he revolutionizes the history of the American West as he takes an apparently contained, local event and opens up several centuries of imperial and local rivalries. Jacoby exposes the entangled human relationships, and their often tragic consequences, that define the region’s history.

Karl Jacoby (Brown Univ.) for Shadows at Dawn: A Borderlands Massacre and the Violence of History (Penguin Press). Jacoby has crafted a beautifully written book, notable for its questioning of historical narrative itself. His reappraisal of the 1871 Camp Grant massacre deeply historicizes violence in the borderlands. Using indigenous sources, he revolutionizes the history of the American West as he takes an apparently contained, local event and opens up several centuries of imperial and local rivalries. Jacoby exposes the entangled human relationships, and their often tragic consequences, that define the region’s history.

James Henry Breasted Prize

Zainab Bahrani (Columbia Univ.) for Rituals of War: The Body and Violence in Mesopotamia (Zone Books, distributed by MIT Press). Zainab Bahrani illuminates the use of often brutal imagery of the body to create and maintain acceptance of violence and warfare from the Sumerians to the Neo-Assyrians. These images Bahrani calls “magical technologies of war,” which appeal at an emotional level to cultural values. This book is original, careful in interpretation of visual evidence, readable, accessible, and well-informed by theory. It will contribute to cross-cultural and cross-temporal analysis of cultural sanctioning of war and violence.

John H. Dunning Prize

Peggy Pascoe (Univ. of Oregon) for What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (Oxford University Press). Peggy Pascoe’s compelling book traces the deployment of miscegenation laws to infuse white supremacy into law and social life in the century after the Civil War. Her meticulous research, in western as well as southern states, shows how local bureaucrats were transformed into race police, charged with regulating the institution of marriage. By historicizing “natural” categories of race, gender, and sexuality, this provocative study reframes our view of the state’s role in human relationships.

Peggy Pascoe (Univ. of Oregon) for What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (Oxford University Press). Peggy Pascoe’s compelling book traces the deployment of miscegenation laws to infuse white supremacy into law and social life in the century after the Civil War. Her meticulous research, in western as well as southern states, shows how local bureaucrats were transformed into race police, charged with regulating the institution of marriage. By historicizing “natural” categories of race, gender, and sexuality, this provocative study reframes our view of the state’s role in human relationships.

John Edwin Fagg Prize

Stuart B. Schwartz (Yale Univ.) for All Can Be Saved: Religious Tolerance and Salvation in the Iberian Atlantic World (Yale University Press). All Can Be Saved takes on centuries of accumulated wisdom on the origins of modernity and the nature of Iberian societies. Through an analysis of the utterances of hundreds of anonymous figures prosecuted by the Inquisition for holding Pelagian heresies of tolerance, the book forces us to rethink the origins of secularism, modernity, and Enlightenment. It also invites us to take a second look at Iberian societies as teeming with dissenters ready to coexist with other religious faiths.

John K. Fairbank Prize in East Asian History

Klaus Mühlhahn (Indiana Univ.) for Criminal Justice in China: A History (Harvard University Press). Mühlhahn’s rich and pioneering book explores the political and social histories of Chinese criminal justice over the sweep of the twentieth century. This deeply researched and elegantly written work compellingly reconstructs the dramatic transformations in legal discourse and social norms about punishment from the late Qing to the Republican and Communist eras. At the same time, it makes marvelous use of memoirs, writings, and testimonials to bring to vivid life the experiences of the millions who became caught up in China’s modern prison system.

Morris D. Forkosch Prize

Christopher Otter (Ohio State Univ.) for The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800–1910 (University of Chicago Press). Chris Otter’s powerfully argued and truly interdisciplinary book calls up many of the metaphors of vision that he so admirably dissects: illuminating, spectacular, enlightening, even brilliant. Writing against the grain of an enormous body of scholarship, Otter’s book shows how technologies of illumination were used to safeguard (rather than deny) personal freedom. His research prompts compelling new questions for historians of liberalism, as well as scholars of visual and material culture.

Christopher Otter (Ohio State Univ.) for The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800–1910 (University of Chicago Press). Chris Otter’s powerfully argued and truly interdisciplinary book calls up many of the metaphors of vision that he so admirably dissects: illuminating, spectacular, enlightening, even brilliant. Writing against the grain of an enormous body of scholarship, Otter’s book shows how technologies of illumination were used to safeguard (rather than deny) personal freedom. His research prompts compelling new questions for historians of liberalism, as well as scholars of visual and material culture.

Leo Gershoy Award

Stuart B. Schwartz (Yale Univ.) for All Can Be Saved: Religious Tolerance and Salvation in the Iberian Atlantic World (Yale University Press). Stuart Schwartz’s All Can Be Saved traces the development of the sentiment of tolerance in the Hispanic world, a region more commonly equated with the enforcement of Catholic orthodoxy. This is an ambitious and engaging book. Based on intensive research in a wide set of archival holdings, impressively wide-ranging in terms of geography and chronology, it advances persuasive and far-reaching claims that transform our understanding of the Iberian Atlantic, popular culture, and early modern religious history.

J. Franklin Jameson Prize

Jean Fagan Yellin (Pace Univ.) for The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers (University of North Carolina Press). Drawing on prodigious research in numerous archives, Jean Fagan Yellin and her assistant editors provide a remarkably vivid portrait of Harriet Jacobs and her world. The documents themselves are captivating, but so too are Yellin’s efforts to interpret them through her superb introduction, extensive notes, helpful biographical sketches, and other editorial elements. These two elegant and beautifully illustrated volumes, along with the accompanying CD-ROM, are an extraordinary resource for researchers and teachers alike.

Joan Kelly Memorial Prize in Women’s History

Peggy Pascoe (Univ. of Oregon) for What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (Oxford University Press). This compelling study is deeply researched, imaginatively conceived, and rigorously argued. Examining miscegenation policies in the United States, Pascoe shows how ideas about marriage and sexuality constructed race and vice versa. Moving away from simple black-white dichotomies, Pascoe examines a broad array of racialized groups and geographical regions. She shows how law is formulated at multiple levels—by clerks, courts, and ordinary people. Pascoe’s broad scope and innovative questions make this book persuasive and important.

Littleton-Griswold Prize

Laura F. Edwards (Duke Univ.) for The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South (University of North Carolina Press). Edwards offers an ambitious recasting of the meanings of “law” in the early American South. She argues against established understandings of a formative era defined by rights discourses, by the work of appellate judges, and by state-national conflict. Instead, Edwards insists that the historiography has forgotten the centrality and the distinctiveness of local law and local practices. She works to reveal a legal culture shaped both by hierarchy and by the need to sustain community “peace.” The People and Their Peace will undoubtedly prove controversial; and yet, the committee agreed that this is a field-changing work, one that all legal historians will need to confront.

Laura F. Edwards (Duke Univ.) for The People and Their Peace: Legal Culture and the Transformation of Inequality in the Post-Revolutionary South (University of North Carolina Press). Edwards offers an ambitious recasting of the meanings of “law” in the early American South. She argues against established understandings of a formative era defined by rights discourses, by the work of appellate judges, and by state-national conflict. Instead, Edwards insists that the historiography has forgotten the centrality and the distinctiveness of local law and local practices. She works to reveal a legal culture shaped both by hierarchy and by the need to sustain community “peace.” The People and Their Peace will undoubtedly prove controversial; and yet, the committee agreed that this is a field-changing work, one that all legal historians will need to confront.

J. Russell Major Prize

Rachel G. Fuchs (Arizona State Univ.) for Contested Paternity: Constructing Families in Modern France (Johns Hopkins University Press). Contested Paternity is a sweeping and deeply archival study of the social, legal, and ideological underpinnings of family forms in France from 1804 to the late 20th century. Describing a transformation from the patriarchal family to the multiple forms we have today, Rachel Fuchs breaks new ground in assigning agency primarily to the actions of countless unwed women who, flouting the Napoleonic ban on paternity investigations, brought suits against the fathers of their children.

Rachel G. Fuchs (Arizona State Univ.) for Contested Paternity: Constructing Families in Modern France (Johns Hopkins University Press). Contested Paternity is a sweeping and deeply archival study of the social, legal, and ideological underpinnings of family forms in France from 1804 to the late 20th century. Describing a transformation from the patriarchal family to the multiple forms we have today, Rachel Fuchs breaks new ground in assigning agency primarily to the actions of countless unwed women who, flouting the Napoleonic ban on paternity investigations, brought suits against the fathers of their children.

Helen and Howard R. Marraro Prize

Thomas J. Kuehn (Clemson Univ.) for Heirs, Kin, and Creditors in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge University Press).Heirs, Kin, and Creditors shows how Renaissance Florentines repudiated family inheritances as a way to cope with contingencies yet still advanced enduring familial goals. Probing larger questions of credit, trust, and kinship, Kuehn reveals the plasticity of inheritance law and the creativity with which Florentines used it. A masterful blend of archival research and legal anthropology, this work moves beyond paradigms of Renaissance individualism to expose the often tense dynamics driving social and family life.

Thomas J. Kuehn (Clemson Univ.) for Heirs, Kin, and Creditors in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge University Press).Heirs, Kin, and Creditors shows how Renaissance Florentines repudiated family inheritances as a way to cope with contingencies yet still advanced enduring familial goals. Probing larger questions of credit, trust, and kinship, Kuehn reveals the plasticity of inheritance law and the creativity with which Florentines used it. A masterful blend of archival research and legal anthropology, this work moves beyond paradigms of Renaissance individualism to expose the often tense dynamics driving social and family life.

George L. Mosse Prize

Stuart B. Schwartz (Yale Univ.) for All Can Be Saved: Religious Tolerance and Salvation in the Iberian Atlantic World (Yale University Press). In this transnational study of early modern popular religious belief, Stuart Schwartz offers an intriguingly counterintuitive picture of Spanish, Portuguese, and New World cultures in the era of Catholic Reformation, presenting their surprising elements of religious tolerance. Schwartz’s compelling analysis of inquisitorial records from both Europe and the Americas traces both the persistence and development of popular attitudes that expressed doubt about, indifference to, or even opposition to official Church dogma on key questions of belief, conversion, salvation, and private sexual practice.

Stuart B. Schwartz (Yale Univ.) for All Can Be Saved: Religious Tolerance and Salvation in the Iberian Atlantic World (Yale University Press). In this transnational study of early modern popular religious belief, Stuart Schwartz offers an intriguingly counterintuitive picture of Spanish, Portuguese, and New World cultures in the era of Catholic Reformation, presenting their surprising elements of religious tolerance. Schwartz’s compelling analysis of inquisitorial records from both Europe and the Americas traces both the persistence and development of popular attitudes that expressed doubt about, indifference to, or even opposition to official Church dogma on key questions of belief, conversion, salvation, and private sexual practice.

James A. Rawley Prize in Atlantic History

Maria-Elena Martinez (Univ. of Southern California) for Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Stanford University Press). In Genealogical Fictions, Maria-Elena Martinez masterfully explains how Spaniards’ concern about the purity of one’s Christian ancestry evolved in America into the castas system, a method of social ranking heavily based on racial distinctions. A provocative work that is attentive to questions of gender and sexuality and how they shaped notions of purity of blood in the Spanish Atlantic world, Martinez’s book presents a novel explication of constructions of “race,” “class,” and “ethnicity” in early Spanish America.

Maria-Elena Martinez (Univ. of Southern California) for Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico (Stanford University Press). In Genealogical Fictions, Maria-Elena Martinez masterfully explains how Spaniards’ concern about the purity of one’s Christian ancestry evolved in America into the castas system, a method of social ranking heavily based on racial distinctions. A provocative work that is attentive to questions of gender and sexuality and how they shaped notions of purity of blood in the Spanish Atlantic world, Martinez’s book presents a novel explication of constructions of “race,” “class,” and “ethnicity” in early Spanish America.

Wesley-Logan Prize

Alexander X. Byrd (Rice Univ.) for Captives and Voyagers: Black Migrants across the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World (Louisiana State University Press). Africans enslaved from the Biafran interior to Jamaica and free blacks resettled from Great Britain and North America to Sierra Leone in West Africa are the subject of this beautifully written and tightly argued study achieved with breathtaking research on three continents. These two streams of migrants are placed within the same analytical space resulting in a nuanced study of migrant societies and the meaning of slavery and freedom for those in constant motion and resettlement. A stunning achievement.

Alexander X. Byrd (Rice Univ.) for Captives and Voyagers: Black Migrants across the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World (Louisiana State University Press). Africans enslaved from the Biafran interior to Jamaica and free blacks resettled from Great Britain and North America to Sierra Leone in West Africa are the subject of this beautifully written and tightly argued study achieved with breathtaking research on three continents. These two streams of migrants are placed within the same analytical space resulting in a nuanced study of migrant societies and the meaning of slavery and freedom for those in constant motion and resettlement. A stunning achievement.