As the COVID-19 pandemic forced educators throughout the nation into an abrupt transition to remote education, I lamented to my parents about the challenges my wife and I faced as we shifted our teaching to distance learning. My father, Dave Lower, reminded me about a similar, albeit far more temporary, challenge he experienced as a public school teacher for Columbus (Ohio) City Schools in the 1970s. A natural gas shortage in 1977, coupled with a brutal winter early that year, forced the temporary closures of industries and schools throughout the North and Midwest. In Columbus, the Columbia Gas Company informed the public school district in late January that the district’s allocation of fuel would be drastically reduced in order to conserve gas for residential use. In just 10 days, Columbus City Schools designed and implemented a plan to continue schooling without classrooms. The resulting program, School without Schools, required unprecedented creativity and fostered cooperation between administrators, faculty, parents, and the business community.

School Without Schools inadvertently hastened desegregation, as it proved that a complete redesign of the district’s busing was not only possible but could be done quickly. David Rees/Wikimedia Commons

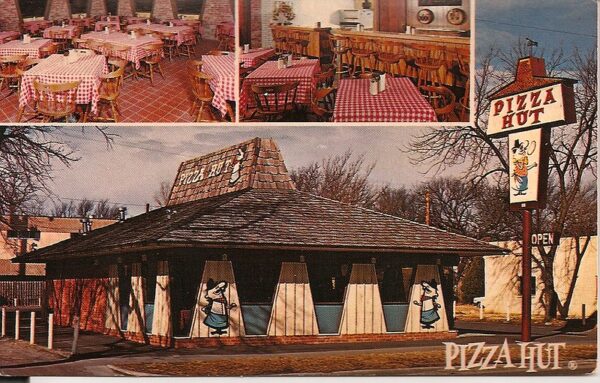

Beginning on February 7, students attended school on one designated weekday at one of the few district buildings that used electric, oil, or coal heating systems. The logistics of providing transportation for many of the district’s 96,000 students to the open campuses were compounded by the fact that busing in Columbus remained segregated. Consequently, the program inadvertently hastened desegregation, as it proved that a complete redesign of the district’s busing was not only possible but could be done quickly. When they did not meet in district buildings, teachers held classes in small businesses and private residences throughout the city. Makeshift classrooms popped up everywhere from shopping malls and restaurants to banks, paint stores, and even bars. My father’s sixth grade class met in a Pizza Hut for two hours, one day a week, before the restaurant opened for lunch.

Local media outlets and businesses proved integral to the program. The Columbus Dispatch printed a daily two-page supplement called “Classroom Extra” that contained brief lessons covering a variety of subjects for different grade levels. Three local television stations donated four hours of weekday programming for local teachers to broadcast lessons. Several radio stations did the same. My dad remembers that the Pizza Hut manager was tremendously supportive, serving the students soft drinks at the conclusion of each session and even hosting a pizza party for the children on the final day of the program.

School without Schools required unprecedented creativity and fostered cooperation between the school administrators, faculty, parents, and the city’s business community.

School officials boasted that administrators, faculty, and parents and guardians cooperated in unprecedented fashion to make the School without Schools program work. This was no small feat for a district with a notoriously fractured school board, less than two years after a bitter teacher’s strike, and less than three months after the city’s voters rejected a modest operating levy. Bringing the program to fruition meant removing bureaucratic roadblocks, including forging a quick agreement to move up the date of spring break by over a month. While the district devised a handbook for individual schools to follow, the guide offered flexibility for individual schools and faculty members to make necessary adjustments as they saw fit.

Parents provided essential support for the program as well. In addition to volunteering to supervise students, parents turned their homes into classrooms. Hundreds opened their homes to students; nearly 700 of the 968 supplemental teaching locations were in private residences.

Individual teachers shouldered the bulk of the responsibility for making the program a success. They willingly set up class space in unique locations and traveled to school buildings and businesses around the city. Officials expected teachers to contact each of their students to communicate meeting locations and times as well as assignments. My father recalls that, in an era without answering machines, reaching parents by phone was a particularly time-consuming responsibility. Like many of his colleagues, he also spent time after each class picking up trash and helping to rearrange the tables before the restaurant opened for lunch.

A sixth grade class met in a Pizza Hut for two hours, one day a week, before the restaurant opened for lunch. katherine of chicago/Flickr/ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Despite the communal effort, the program was not without its challenges. On a fundamental level, the district could not mandate attendance or participation in classes held at supplemental locations. My dad’s class never had perfect attendance (even though there was pizza involved!). Some students failed to complete any at-home assignments. Much like our current situation in which many teachers are trying to maintain student learning through the end of the semester, the faculty in Columbus City Schools understood that the program could not possibly serve as a perfect substitute for conventional education. Before the closure, my dad and his fellow sixth grade teachers agreed to focus their instruction on math and language arts, with an emphasis on reinforcing existing educational skills and content rather than teaching new material. With the buildings closed, teachers could not print any supplemental materials on school mimeograph machines. Despite these limitations, school leaders deemed the program successful as an emergency measure. While officials conceded that not much new instruction took place, they found no evidence that the missed classroom time impaired the students’ overall education.

Makeshift classrooms popped up everywhere from shopping malls and restaurants to banks, paint stores, and even bars.

Thanks to the internet and the prevalence of home computers and cell phones, today’s instructors have some significant advantages teaching students remotely compared with their counterparts in 1977. However, as my father was quick to remind me, he and his peers had the benefit of knowing that their predicament had a definitive end date while ours has no foreseeable “return to normalcy.” The brief, unique history of School without Schools reminds us that shuttered classrooms need not equate to teaching in isolation. Comradery and cooperation between administrators, faculty, and local communities offer opportunities in the midst of a crisis. At a minimum, the program demonstrated that with flexibility and community, innovative solutions can be found to manage remote learning. Perhaps even involving pizza!

Chad Lower is an assistant professor of history at Brazosport College. He tweets @DrChadLower.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.