In May 1942, historian Allan Nevins (see his bio and presidential address) created a national controversy about American students’ lack of knowledge about the facts of their nation’s history. Pointing an accusing finger at history teachers in the schools and colleges, he charged that “it is distressingly true that our young people are all too ignorant of American history when they leave high school or even college” (“American History for Americans,” New York Times, May 4, 1942, SM6). Nevins and the staff of the Times followed up with a series of investigations that reinforced this perception that American history was being squeezed out of school and college classrooms, setting off a mini-firestorm of controversy in newspapers across the country and even into the halls of Congress.

In May 1942, historian Allan Nevins (see his bio and presidential address) created a national controversy about American students’ lack of knowledge about the facts of their nation’s history. Pointing an accusing finger at history teachers in the schools and colleges, he charged that “it is distressingly true that our young people are all too ignorant of American history when they leave high school or even college” (“American History for Americans,” New York Times, May 4, 1942, SM6). Nevins and the staff of the Times followed up with a series of investigations that reinforced this perception that American history was being squeezed out of school and college classrooms, setting off a mini-firestorm of controversy in newspapers across the country and even into the halls of Congress.

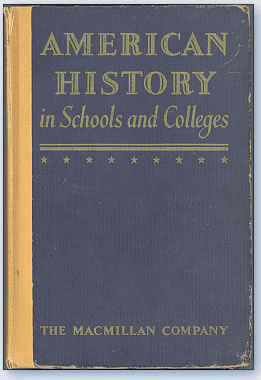

In response, the American Historical Association joined the National Council for the Social Studies and the Mississippi Valley Historical Association (the precursor to the OAH) in a wide-ranging assessment of American History in Schools and Colleges—the latest addition to our online archives. This report casts an ambitious net, which “describes the extent and quality of popular knowledge of American history; it weighs the functions of history and shows why the subject deserves attention; it surveys history programs in the schools and colleges and calls attention to the numerous popular agencies of historical instruction; it redefines the place of history within the social studies field; it recommends the minimum content of American history courses at the various levels of instruction; it outlines a program for the education of the history teacher; it discusses the relation between the public and the teacher; lastly, it makes a series of other recommendations concerning the teaching of American history in the schools and colleges.”

Their observations on each point are interesting on their own merits, and provide a useful point of comparison for current discussions about curricula in schools and colleges in the age of assessment. The results of the committee’s “Test of Understanding of United States History” (which was given to samples of high-school students, military students, social studies teachers, adults, and people listed in Who’s Who) is particularly interesting, as a view of what counted as history 65 years ago.

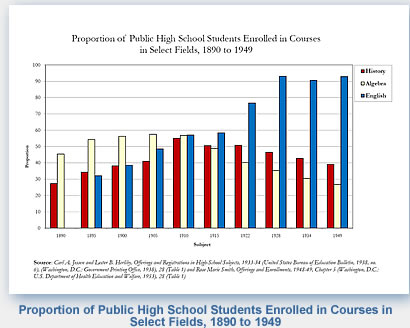

It is hard to say whether the report had much of an effect—the New York Times only gave it a passing mention in its book review section. But as Ian Tyrrell observes in Historians in Public, there are dangers inherent in pitting one area of the discipline against others in curricular debates. At the high school level, the proportion of students taking history courses continued the slow and steady decline that began decades earlier (table below), but the proportion of students enrolled in U.S. history courses increased significantly into the 1960s, displacing the history of other parts of the world.

It is hard to say whether the report had much of an effect—the New York Times only gave it a passing mention in its book review section. But as Ian Tyrrell observes in Historians in Public, there are dangers inherent in pitting one area of the discipline against others in curricular debates. At the high school level, the proportion of students taking history courses continued the slow and steady decline that began decades earlier (table below), but the proportion of students enrolled in U.S. history courses increased significantly into the 1960s, displacing the history of other parts of the world.

Despite the AHA’s participation in the effort that produced this report and the larger international interests of the country in the post-war years, the net effect of the controversy was a reduction in attention to the history of the rest of the World for more than a generation.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.