Are enrollments in undergraduate history courses stabilizing? kasto/depositphotos

After years of declines, undergraduate enrollments in history courses held steady in the last academic year. Last summer, the AHA conducted its third annual survey of history departments and joint academic units, and received 120 complete responses for the past four academic years, the most recent of which was 2017–18. The responses suggest that the overall number of undergraduate students enrolled in history courses changed little from 2016–17. Enrollments slipped down less than 0.5 percent at US institutions. When Canadian institutions are included in the total, enrollments were almost identical (up less than 0.01 percent).

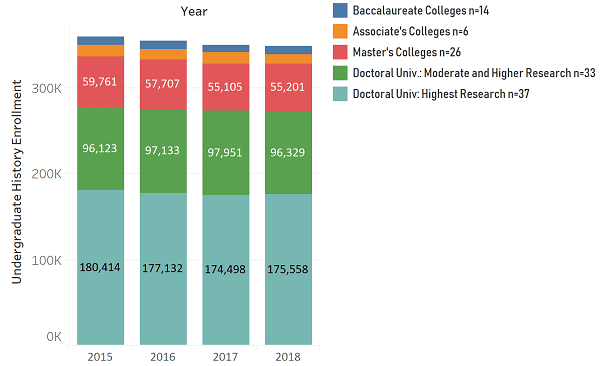

This year, the AHA received complete data on the past four years from 120 respondents: 110 four-year institutions and 6 two-year institutions in the US, and 4 four-year institutions in Canada (Fig. 1). Among institutions responding to this year’s survey, the total student enrollment in history courses declined 1.6 percent from the academic year 2014–15 to 2015–16, and another 1.2 percent in 2016–17. The number then flattened out in 2017–18.

For the four-year period covered in this most recent survey, the aggregate decline was 2.7 percent: a loss of 10,215 student enrollments within these 120 institutions. The aggregate decline among the US-only group over these four years was 3.1 percent. This marks an improvement from the 7.7 percent total decline we reported last year for 2013–14 through 2016–17.

Fig. 1: Total undergraduate enrollment in history courses, by institution type.

Because different institutions respond to the survey each year, longer-term trends are impossible to quantify. Only a handful of two-year institutions provided enrollment data, making it difficult to draw conclusions about trends affecting community colleges. But the number and variety of responding institutions do present a robust and, likely, representative sample for four-year colleges and universities.

Any sign of stabilization should be encouraging to historians at a broad range of institutions.

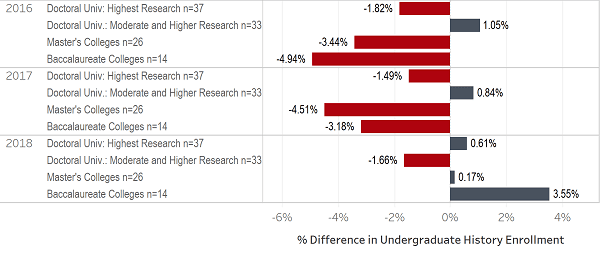

The improvements are clear across the four institution types best represented in the survey responses (Fig. 2). The year-to-year change was negative for three out of four groups in 2015–16 and 2016–17, but positive for these groups in 2017–18.

Any sign of stabilization should be encouraging to historians at a broad range of institutions. The number reporting declines was about equal to the number reporting otherwise: undergraduate enrollment was flat or positive at 59 and negative at 61. And, as in previous years, experiences at individual institutions varied dramatically. Some small departments experienced vast changes in enrollment, down or up more than 30 percent since 2014–15. Changes were less dramatic at most larger departments due to larger undergraduate enrollments.

A few larger institutions reporting annual enrollments of more than 3,000 did change by large margins over the reporting period. Of the 15 that have increased enrollment by 15 percent or more since 2015–16, 6 were large enough to have enrollments of 3,000 or more in 2018. But 28 experienced declines of more than 15 percent over the past four years; 8 of them had more than 3,000 undergraduate enrollments in 2018.

Taking Positive Steps

Qualitative responses to the survey show that historians at many institutions are taking action to increase undergraduate recruitment and retention in courses, minors, and majors. They often start with introductory courses, where the largest number of students encounter history. As in previous years, variables like general education requirements, the demography of the institution’s student population and region, and career prospects in fields traditionally associated with a history major (like law and teaching) strongly influence how many students take history courses. But historians still have agency.

Those departments reporting success seem to share an approach that focuses on student interests and goals. Respondents described efforts to “meet students where they are” by asking whether course topics and content were appealing to students and making revisions when necessary.

“We are fortunate that we touch every student at the university” because of a required course, one respondent explained. “Focusing our efforts there [has] enabled us to not only increase our enrollment in undergraduate courses while university enrollment has been flat, but to increase the number of our history majors.” Another institution saw a 40 percent increase in student credit hours in 2017–18 over the previous year, “following an aggressive recruiting push and the decision to [offer] a certain number of classes online and to revamp some existing course[s] to make them more appealing (we hope).”

Fig. 2: Rates of undergraduate enrollment change, by year and institution type.

Historians say their curricular work, including strategic reflection on the pathways that non-history students take to their degrees, is increasingly important. At many institutions, students (and faculty) have more choices under revamped general education requirements. Newer programs, often designed around skills-based learning outcomes or broadly conceived ways of thinking, allow historians to develop innovative courses for all students. One respondent hoped that a new general education program would allow history to contribute to “a wider variety of required course categories to attract students, who discover new connections between History and a range of different disciplines and thematic programs.”

The flip side of these opportunities, however, is increased competition from courses offered by non-historians. As one respondent reported, general education reforms meant that “academic units competed with one another for undergraduate seats. This also means that fewer of those students who think they do not like history find their way into our classes to be persuaded otherwise.”

Efforts to address enrollment declines often start with introductory courses.

Critics regularly say that students are fleeing history because they put off by the supposedly liberal political agenda of history faculty, as expressed in the topics of the courses they teach. Data in a 2014 analysis in Perspectives cast doubt on this connection, and this year’s qualitative responses again show that historians in resilient departments have broad professional interests.[1] Political economy and warfare coexist with immigration and gender; it is not an either/or choice. One respondent said, “We have designed courses that appeal to the interests of students (WWI, WWII, history of science, history of food, history of sexuality), and this has brought enrollments back up. Critical [to these efforts] has been designing courses that appeal to women students, since they make up 60 percent of our campus student body but 40 percent of history majors.”

Students might also be looking for different course formats. “We are considering dropping the traditional survey courses, whose enrollments have plummeted,” reported one institution. “We are also going to be talking about adding a general introductory course (along the lines of Yale’s The World [circa] Year x or Michigan’s History 101).” Another department has felt the pinch most in advanced seminars: “We don’t have as many majors as we used to, and even though we’ve integrated the upper-level courses into the general education curriculum whenever possible, we struggle to attract non-majors. It’s not uncommon for a faculty member to have to cancel a seminar and replace it with a survey or some equivalent administrative task[.] . . . Attracting more majors and more actively promoting our classes and the major as a whole is our strategy for dealing with the problem, but progress has been slow.”

This year’s qualitative responses show that historians in resilient departments have broad professional interests.

Departments that continue to struggle with maintaining enrollments seem to lack an active, holistic strategy supported by faculty, even when undergraduates must take an introductory course. Enrollments fall in the context of budget cuts and an anemic academic job market. The risks of low morale and worsening working conditions are serious. “Enrollment is slowly declining, especially in upper division courses,” said one respondent. “We flourish because we teach a required course, but half of our faculty is NTT [non tenure-track] and are devoted to teaching this course. Our major is not growing, and neither is our TT/T [tenure-track and tenured] faculty. This threatens the viability of our graduate program and causes service to become a bigger burden for TT/T faculty.”

The recession of 2008 led to changes in K–12 education policy and cuts to funding earmarked for hiring and training teachers. The number of students intent on becoming history educators thus declined sharply. These factors continue to shake some departments, especially at regional comprehensive institutions. One respondent wrote, “Most of our majors and minors traditionally were in teacher education. Because there are so few of those students currently, we have struggled to find new ways to garner majors and minors. In 2005, we had over 500 majors. As of spring 2018, we had 126.”

Although such large-scale changes can make individual historians feel powerless, the AHA continues to advocate for quality history education at all levels and will continue to initiate and support professional development through its programming and publications. Additionally, the AHA’s new History Gateways project focuses on rethinking a wide range of introductory courses, including general education courses, to advance learning at what is often historians’ first and only point of contact with students. While this year’s news about enrollments is heartening, we should not assume that we have done all we can to address the downward trend of previous years. The AHA will therefore continue to survey departments about enrollments and share with Perspectives readers strategies that work.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.