The Kennedy Caucus Room of the Russell Senate Office Building has been the site of some of the most famous Senate hearings in history, from the Titanic sinking to Watergate. On June 25, it welcomed journalists Andy Glass and Roger Mudd, along with historian Donald A. Richie from the Senate Historical Office, for a discussion commemorating the 50th anniversary of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

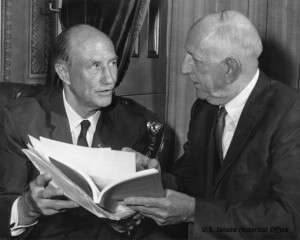

Senators Strom Thumond of South Carolina and Richard Russell of Georgia opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

credit: U.S. Senate Historical Office

While many are familiar with the tumultuous public debate that surrounded the passage of the Civil Rights Act, perhaps less is known about the legislative side of the story. When the bill came before the Senate on March 30, 1964, a “Southern Bloc” of 18 senators, led by Richard Russell (D-GA), launched a filibuster to prevent passage of what they felt was a deliberate scheme to destroy the “Old Confederacy.”

Roger Mudd, a familiar face in American broadcast journalism, was congressional correspondent for CBS News at the time. Andy Glass, now a contributing editor at Politico, was chief congressional correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune. As members of the self-proclaimed “Cloture Club,” Mudd and Glass were part of a small group of reporters that provided first-of-its-kind “zone coverage” of the 57-day filibuster. The journalists even gained personal access to the senators themselves. Mudd, for example, remembered Sen. Russell as having a “remote,” “dignified,” and “generous” character, while Glass concluded that the Southern Bloc was made up of men who were “not always honorable.”

Because cameras and sketch pads were barred from the Senate chamber, the journalists found creative ways to record what was happening during the long, “arcane” days of the filibuster. Mudd recalled that CBS employed sketch artist Howard Brodie to memorize senators’ faces and run outside to make drawings for the nightly news report. Public interest in the journalists’ efforts also grew. Taken aback when a group of tourists gawked at him as he arrived at his usual post on Capitol Hill, Mudd began to perceive the ways in which his profession was evolving. New awareness (and concerns) about the mass effect of television news broadcasting were beginning to enter American social consciousness.

On June 10, 1964, the record-breaking filibuster ended when cloture was invoked for the first time in history on a civil rights bill. The bill passed the Senate and was signed into law on July 2. Senate Historian Don Ritchie, who moderated the discussion, likened the Cloture Club’s coverage of the congressional debate to “writing the rough draft of history.” But not only were the journalists “covering” history, they were making it. Glass and Mudd’s spirited efforts to translate “boring but important” congressional actions into compelling news helped change the face of modern journalism.

Now the last living members of the Cloture Club, the journalists were asked what they were most proud of about their work reporting on the filibuster. Glass answered that he was grateful the public trusted his coverage even though he was only 27 years old. For Mudd, his proudest accomplishment was “nobody knowing how I thought.” By that method, these reporters voiced a story that tensions, hostility, and disunity could have otherwise rendered obscure.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.