There is an outer-space themed punk band, The Phenomenauts, who wrote a song asking a question, “It is an infinite frontier, why should we stop here?” A personal favorite, I found myself humming this song on the walk back to AHA Headquarters after attending annual meeting Session 161: Environmental History and Outer Space: Linking Terrestrial and Extraterrestrial Natures across Time. As one of the youngest attendees of the NYC meeting, I found inspiration and a reassured comfort in the panelists’ remarkable expansion of the frontiers in the two fields, both of which are personal interests. In the post-bac, pre-grad world I occupy, it is intimidating to see potential topics of theses and dissertations snapped up by more established scholars. The panelists, however, went on to remind me that the boundaries of history are almost always expanding, intersecting, amalgamating, and looking back and that new projects are bound to coalesce just like a fresh star system.

The first panelist, Michael Rawson from CUNY’s Brooklyn College and Graduate Center, presented a history of environmental thought on the Moon. Long before Apollo 11 touched down on its surface, loads of scientific conjecture regarding the Moon’s environment and what sort of life it might harbor had been put forth. Prominent thinkers, going as far back as Plutarch, with scientific figures as prominent as Galileo and Kepler, helped expand ideas of nature to all corners of the universe much earlier than one might think. While some claims had no scientific merit, like Francis Godwin’s 17th-century novel The Man in the Moone in which a man is carried to the Moon by birds, other concepts fit very well into modern ideas of nature, such as lunar life being adapted to the lunar environments.

Neil Maher of Rutgers University/New Jersey Institute of Technology then explicated second-wave feminism’s influence on NASA through an examination of a series of three linked historical moments. From the onset, Maher made clear that he found NASA to have made an environmental justification for the initial exclusion of women from NASA missions. As space travel can be seen as bringing your physical earthly environment with you, to include women would have required “his and her” equipment. It would not be until the Space Shuttle years, when certain members of space-faring crews no longer required space suits, that Sally Ride finally became the first American woman to fly to space. Despite this, Ride had been beaten, 20 years earlier, by Soviet Valentina Tereshkova. Tereshkova’s flight was quickly incorporated into the Cold War political arena, allowing Premier Nikita Khrushchev to boast that communist women walked alongside men in all concerns. Maher closed by arguing that feminist debates reached a high water mark with public discussion of female astronauts.

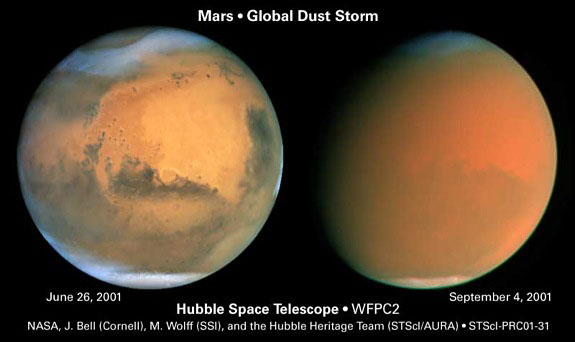

The final participant of the session was University of Virginia’s Lisa Messeri, an anthropologist by trade, who examined how climate sciences have been used in modelling Earthly, Venusian, and Martian environments. The great takeaway from her dive into comparative planetology was the back and forth nature of the research. She began with showing how the projection of our understanding of Earth’s climates onto the two neighboring planets would eventually turn around, and atmospheric models of Earth on would draw from what had been learned of Mars and Venus, such as the observance of a planet-wide dust storm on Mars and the runaway greenhouse effect on Venus. Messeri closed out the presentations with remarks that in the expansion of the usage of the term “Anthropocene,” humanity should be recognized as an active geological force, and more importantly, a planetary force!

Since arriving at the AHA’s DC Headquarters in July, I have definitely emerged as the cheerleader for outer space history. The experience of attending the annual meeting, and more so the session solely focused on these spacey histories, proved incredibly rewarding. It fostered a deeper enthusiasm not only for this area of research but also for exploring new approaches to the material itself, effectively grounding my pre-grad research woes.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.