The Library of Congress contains over a million dissertations. Each of these works represents an average of four years of work by a specialist who has diligently and intelligently scanned, sorted, read, categorized, assessed, and annotated hundreds or thousands of primary and secondary sources. The scale of this work is staggering—literally billions of person-hours in dissertation work alone, not to mention the research that went into the millions of other books those dissertations share shelf space with, as well as tens of millions of articles and countless other scholarly creations.

Undoubtedly this tremendous production and sharing of knowledge is worthy of awe. Yet much—indeed, most—of what we do as scholars does not show up in publications such as these. These printed texts are merely the tip of the iceberg—the small portion of our thought that is visible to everyone, but which sits atop a hidden mountain of judgment and research. This submerged bulk of our expertise resides in notes on paper sitting in our filing cabinets, on our hard drives, and in the recesses of our minds. If some of this knowledge surfaces at all, it is usually as ghostly traces within the summaries and conclusions of a book or article, or perhaps in the more lasting embodiment of a footnote

Simple reflection on the process of becoming a historian makes one realize that apart from serving as the basis for publications, bits of this underlying layer have tremendous value by themselves, and have long been shared, albeit in limited ways. A great deal of our formative experience as undergraduates and graduate students, as well as in our careers, consists of informal communications such as "this book is extremely useful for understanding Reconstruction," "the 1880 manuscript censuses are an excellent source for understanding the social structure of American cities," "the use of the word ‘passion' is unusual in diaries of this age," or "you can skip these passages ofThe Wealth of Nations unless you plan to focus on the Scottish Enlightenment (or are a glutton for punishment).”

Those judgments may occasionally seem offhand, but often they are distillations of years of education, experience, and thought. They also remain, for the most part, in the realm of what may be called professional folk wisdom, passed along from one person (a mentor or colleague) to the next. Graduate students learn to tease such insights out of footnotes, bibliographies, and even acknowledgements. Only rarely may these forms of knowledge take a more fixed shape, as when the American Historical Association mixes together and boils down assessments of important books to create the invaluable Guide to Historical Literature.

While the annotated bibliographies of the Guide have been the salvation of thousands of budding historians, many other scholarly judgments and records may be of great value to smaller audiences or even individual scholars or students, thus not meriting their own publication or widespread dissemination. Careful notes describing in detail the contents of each letter in a remote archive, shrewd marginalia on photocopies that might prove useful to a fellow specialist, a bibliography for a book project never pursued that could serve double duty as an orals reading list for a graduate student, perceptive abstracts of opaque works—these scholarly productions have been, for the most part, disposable and disposed.

Recent Trends in Computing and Their Significance for Scholarship

Three recent trends in computing may make the sharing and aggregation of this hidden knowledge not only likely, but possibly have a significant impact on history and the humanities. The first trend is the inevitable increase in the amount of research that is going on online, and a commensurate use of digital tools to marshal scholarly resources. It has been over 20 years since ProCite and SciMate first provided PC users the means to store references and automatically generate bibliographies. Now the field is maturing as the market leader EndNote is being challenged by web-based applications such as RefWorks as well as a half-dozen open-source projects, including Zotero, the project I co-direct. These applications take the basic work of saving citations and recording one's thoughts on those objects of research, and moves them into a digital environment that enables better searching and analysis, easier integration with the writing process (adding footnotes and bibliographies), and more sophisticated organization (unlike a 3×5 card, a digital note can be in two or more places at one time).

Although a recent University of Minnesota survey found that only 8 percent of humanities scholars currently use reference managers like EndNote (compared to 36 percent in the social sciences), the usage of these tools will likely spread in the coming years. Graduate students are already over 50 percent more likely than existing faculty to use such software, and as historians of all ages become more comfortable with digital research, their use of digital tools to assist their studies will likewise expand.1 Moreover, with vast new historical resources rapidly moving online due to ambitious efforts such as Google’s library digitization project, we will all need better ways of dealing with countless online documents without printing everything out or using note cards.

The second trend is the rise of "social computing," which sounds like laptops at teatime but is instead characterized by a networking together of individuals and their interests and opinions. A successful implementation of this idea is the curiously punctuated web site, del.icio.us, which enables users to share and tag (provide descriptive keywords for) web pages they have found. Such "bookmarking" has occurred for years in individual web browsers; by taking that process off personal computers and putting it online, it allows users of del.icio.us to see what others with similar interests have found on the web.2 The collaborative filtering of large masses of information and enabling discovery of relevant resources based on the aggregation of many individual assessments and recommendations—as when Amazon.com highlights books you might find appealing—is a critical feature of social computing.

The principles of social computing are slowly making their way into academia. For the past two years, the Nature Publishing Group has been running Connotea, a site that allows researchers, scientists, and clinicians to "organize, share, and discover" articles of interest.3 PennTags has enabled the faculty and students of the University of Pennsylvania to add tags and longer descriptions to their library’s holdings, and to relate those millions of cataloged items to web-based documents.4 Silicon Valley venture capitalists are rushing to invest in social computing sites for bookworms such as LibraryThing and Shelfari.5 These services enhance scholars’ ability to find resources that match their research needs, and begin to show the power of exposing and aggregating previously unpublished scholarly appraisals and knowledge.

The third computing trend is a growing emphasis on "semantic" information on the World Wide Web. Until now, the Web has largely been about the presentation of documents (web pages) and the connections between them (hypertextual linking). The web browser has been a fairly "dumb" window onto the Internet, focusing more on the formatting of pages than understanding their contents. For example, when you are looking at a book listing on Amazon.com, the browser has no idea that the current web page concerns a book. Semantic information—author, title, publisher, and the like—is increasingly available on web sites, albeit encoded in hidden formats. Intelligent software can illuminate and manipulate this structured information, which is the information academics really care about.

Zotero and the Convergence of Computing Trends

At the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, we decided to take advantage of these three trends by creating Zotero, software that allows users to build, organize, and annotate their own research collections with a high level of integration with online texts and databases.6 Zotero is an extension to the popular open-source web browser Firefox, which is quickly becoming the preferred alternative to Microsoft’s Internet Explorer because of its greater security and the ability to enhance it with extensions like Zotero. (Since IE’s underlying code is closed, rather than open, it is also impossible to build robust applications such as Zotero on top of it.)

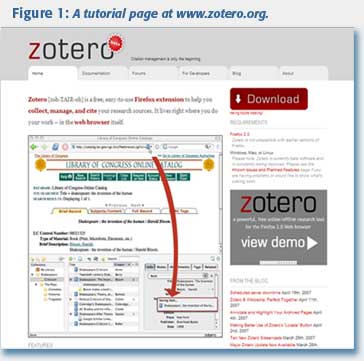

The signature action of Zotero is its ability to sense and then automatically save the complete information about a book, article, or other object of scholarly research, which it often does by looking around for semantic information on or near a web page. For many major research sites and databases, such as JSTOR, ProQuest, and Google Books, as well as most libraries' online catalogs, icons for objects on the page, such as books, will appear at the top of the browser and can be added to one's personal research collection with the click of the mouse (see Figure 1).

Once saved into Zotero, you can drag and drop texts and images into various collections (folders), search your collections in simple and advanced ways, export citations into various word processors, including Microsoft Word, and create “reports,” or documents summarizing your research for posting to the Web (or yes, even printing out, if you prefer). You can write unlimited notes on an item or sets of items you have saved, and even use virtual Post-it notes and a yellow highlighter to markup stored documents from the web. PDFs and other full-text documents can be attached to items; for some sites, like JSTOR, this happens automatically.

Once saved into Zotero, you can drag and drop texts and images into various collections (folders), search your collections in simple and advanced ways, export citations into various word processors, including Microsoft Word, and create “reports,” or documents summarizing your research for posting to the Web (or yes, even printing out, if you prefer). You can write unlimited notes on an item or sets of items you have saved, and even use virtual Post-it notes and a yellow highlighter to markup stored documents from the web. PDFs and other full-text documents can be attached to items; for some sites, like JSTOR, this happens automatically.

We believe that this easy-to-use research environment and the way in which it takes advantage of semantic bibliographic information on the Web instantly makes Zotero an attractive choice for managing one's research. Hundreds of sites already seamlessly integrate with Zotero, with more being added each week. Some research sites, like Copac, the union catalog of major libraries in the United Kingdom and Ireland, have automatically become compatible when they have added semantic formats to their site.7 Since the “semantic web” is not fully here yet, however, other sites require us to write “translators” to extract scholarly information from their web pages.

Just as one can import objects of research into Zotero with one click, you can also easily export parts of your collection (or your entire personal Zotero "library" of references, bibliographies, notes, and other products of research that might be helpful to colleagues or students) to send to other users of the software.

Such exports begin to show the potential of widespread scholarly sharing, but it is the next phase of the Zotero project, coming this fall, when social computing will combine with semantic computing to enable serious advances in historical research and collaboration. We are currently building a web server through which Zotero users and groups can recommend and exchange resources. Once the Zotero server goes online this year, users of the software will be able to do more than just one-to-one transfers since this "mothership" will contain the combined wisdom of hundreds of thousands of scholars.

The benefits of such networking and the emphasis on semantic entities like books, articles, and letters opens up new possibilities for scholarly communication. A group of historians interested in a topic lacking a chapter in the Guide to Historical Literature will be able to build a bibliography of important works in their field collaboratively, which then could be shared with students. Scholars will be able to track more easily publications of interest in their fields and hear of archival documents newly discovered or scanned by other Zotero users, based on tags, recommendations, and the holdings of personal collections. Historians from around the globe will be able to combine virtually to annotate a primary source that has just been digitized and placed online. Most intriguingly, this interaction of people, tools, and resources—what we might call an “ecology of scholarship” (which undoubtedly will include software other than Zotero)—perhaps will lead to the discovery of new knowledge by aggregating and analyzing our shared wisdom.

— is the author ofEquations from God: Pure Mathematics and Victorian Faith (Johns Hopkins Press) and coauthor, with Roy Rosenzweig, of Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web (University of Pennsylvania Press). He is an assistant professor of history and director of research projects at the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. He would like to thank Roy Rosenzweig for helpful comments on a draft of this article.

Notes

1. University of Minnesota Libraries, “A Multi-Dimensional Framework for Academic Support: A Final Report,” a report to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, June 2006, p. 32. Available at www.lib.umn.edu/about/mellon/UMN_Multi-dimensional_Framework_Final_Report.pdf.

2. del.icio.us, available at https://del.icio.us.

3. Connotea, available at https://www.connotea.org.

4. PennTags, available at https://tags.library.upenn.edu.

5. LibraryThing, available athttps://www.librarything.com; Shelfari, available at https://www.shelfari.com.

6. Zotero, available at https://www.zotero.org. The Zotero project is generously funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

7. Copac, available at https://copac.ac.uk.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.