The June issue of the AHR is the last that will appear under my editorship, as my term ends August 1. There is no obvious theme in this issue, other than the ongoing effort to publish history in a wide variety of registers and on a broad range of topics.

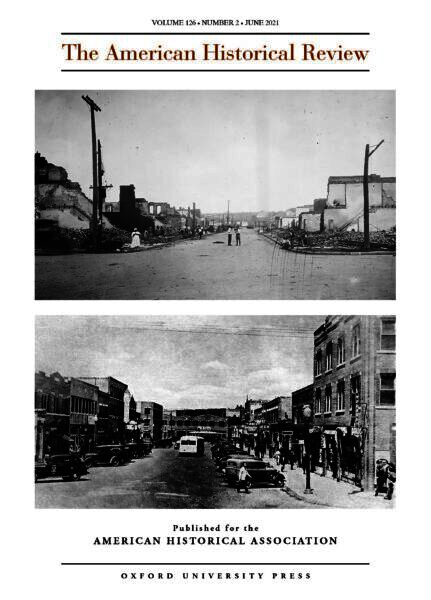

May 31 and June 1, 2021, mark the centenary of one of the worst outbreaks of anti-Black violence in American history, when thousands of whites attacked Tulsa’s vibrant Black community, Greenwood. In the aftermath of the violence and destruction, reports estimated that as many as 300 Black people had been killed and every significant structure in Greenwood had been destroyed or severely damaged. The top photo illustrates this devastation from Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street. The lower photo shows the same intersection less than two decades later. As Karlos Hill points out in his essay about ongoing efforts to memorialize the massacre, survivors and their descendants remain resilient. Top photo: “After the race riots, June 1st, 1921, Tulsa, Okla.,” American National Red Cross photograph collection, Library of Congress; bottom photo: with permission of the Greenwood Cultural Center, Tulsa.

The issue features three History Unclassified essays, all of which speak to the problem of “silenced” histories. In “On Silence and History,” Lilia Topouzova (Univ. of Toronto) explores the challenges of working with a purged archive and fragmented oral histories to reconstruct the little-known story of the Bulgarian gulag. In grappling with these limits, she considers the multiplicity of the lived experience of 20th-century eastern European communism and its contradicting realities, emancipatory and repressive at once.

Wrestling with a different kind of silence entangled with trauma, Joy Neumeyer (European Univ. Institute) writes about her experience as a survivor of domestic abuse while pursuing a PhD. In “Darkness at Noon: On History, Narrative, and Domestic Violence,” Neumeyer explores her dawning recognition that while she could produce evidence about her experience, other judges—including fellow students, faculty, and her university’s Title IX office—would weave that evidence together to make their own meaning. Her essay attempts to reconcile the conception of history as narrative with the pressing need to seek truth and justice.

A third essay examines the long silence surrounding the Tulsa massacre of June 1921. On the 100th anniversary of the deadly white rampage in the vibrant Black neighborhood of Greenwood, Karlos Hill (Univ. of Oklahoma) describes his efforts to align his scholarly expertise with addressing the polarizing legacies—and continued silences—of the 1921 violence. His essay encourages other historians to pursue such “community-engaged history.”

Seven full-length articles range from the nature of policing in colonial Guatemala to dissident art movements in late-socialist East Germany. In “Walking While Indian, Walking While Black: Policing in a Colonial City,” Sylvia Sellers-Garcia (Boston Coll.) focuses on policing reforms that took place during the last decades of colonial rule in Guatemala City in the late 18th century. Based on her examination of criminal cases and legislation, she argues that these reforms prompted the arrests of non-European men for vagrancy and carrying weapons. The result of this targeted policing was the creation of a criminal profile inflected by race, gender, and class. These police methods and mindsets have created a legacy of colonial policing into the present, Sellers-Garcia suggests.

A second article examines the nature of governmentality in the long 19th century. In “The Unexceptional State: Rethinking the State in the Nineteenth Century,” Nicolas Barreyre (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales) and Claire Lemercier (French National Center for Scientific Research) compare the historiographies of state formation and function in the postrevolutionary era in the US and France. Their article recovers a common repertoire of statecraft that hinged on fostering consent of key segments of the population, and the organization of the work of the state into nonbureaucratic forms, a particular enmeshing of public and private initiatives that reconfigures what we mean by “the state.”

The remaining five articles focus on various dimensions of the 20th century. Two consider social upheavals associated with World War II and its immediate aftermath. In “Europe’s Forgotten Unfinished Revolution: Peasant Power, Social Mobilization, and Communism in the Southern Italian Countryside, 1943–1945,” Rosario Forlenza (Libera Univ. Internazionale degli Studi Sociali) draws on anthropological theory to reconstruct the revolutionary experiments that burst out in the Italian countryside in the latter days of the war, as groups of peasants took over dozens of villages in the Mezzogiorno. Forlenza uses these forgotten peasant republics to consider how social revolutions can unfold without the decisive leadership of a pre-existing vanguard whose ideas and expectations can overdetermine patterns of revolt. Similarly, by looking at postwar Japan under US occupation, Deokhyo Choi (Univ. of Sheffield) asks what decolonization looks like on an empire’s home front. In “The Empire Strikes Back from Within: Colonial Liberation and the Korean Minority Question at the Birth of Postwar Japan, 1945–1947,” Choi argues that the “liberation” of Korean imperial subjects living in Japan after the war became a critical locus of US-led democratization and Japan’s transition from a multiethnic empire to a so-called “mono-ethnic nation,” shaping Japan’s postwar order. Choi’s article offers a new vantage point for considering decolonization’s impact on metropolitan societies.

The issue features three essays which speak to the problem of “silenced” histories.

A second article on postwar Japan, “‘Toilet Paper Panic’: Uncertainty and Insecurity in Early 1970s Japan,” looks at the nature of anxieties around consumption and middle-class status during the 1970s. Deconstructing the nature of a 1973 so-called “panic” over the disappearance of toilet paper from Japanese shelves, Eiko Maruko Siniawer (Williams Coll.) treats consumer anxiety as a response to sweeping economic challenges that destabilized daily life and threatened to upend middle-class lifestyles after a period of sustained high growth. Buffeted by insecurity and uncertainty, she argues, the Japanese middle class had never seemed as vulnerable as it did in the early 1970s.

If the articles on Italy and Japan stay fixed in place, Benjamin A. Lawrance (Univ. of Arizona) and Vusi Kumalo (Nelson Mandela Univ.) examine a far more peripatetic aspect of the decolonial moment. In “‘A Genius without Direction’: The Abortive Exile of Dugmore Boetie and the Fate of Southern African Refugees in a Decolonizing Africa,” they zero in on the experience of a South African writer and apartheid expatriate to interrogate the distinction between exiles and refugees. Cases like that of the relatively obscure Dugmore Boetie shift attention away from refugee reception and toward motives for flight, speaking to ad hoc strategies of escape and survival characteristics of those without privileged networks prior to the formation of global antiapartheid activist networks.

The final article in the June issue examines how experimental art staged in East Berlin galleries and streets from the mid-1970s until 1989 was used to reconstitute the relationship between art, social life, and citizenship under socialism. In “Grassroots Glasnost: Experimental Art, Participation, and Civic Life in 1980s East Berlin,” Briana J. Smith (Harvard Univ.) shows how experimental artists took advantage of the gaps in party control in order to access—and construct—a second public sphere in which open communication, imagination, and critique proved possible. These artists, she claims, helped ignite a grassroots glasnost parallel to top-down reforms emanating from the USSR, contributing to a spirit of political ferment across East-Central Europe in which more expansive forms of socialist citizenship could be tested.

Two other features round out this very full issue: a critical reappraisal of Jackson Lears’s classic of post-New Left cultural history, No Place of Grace (1981) by Andrew Seal (Univ. of New Hampshire) and a cluster of reviews of seven short biographies of African leaders, all published in Ohio University Press’s Short History of Africa series.

It has been an honor and a pleasure to edit the American Historical Review and to work with the many staff members at both the AHR and the AHA who make the journal what it is. I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to editorial board members, manuscript readers, and book reviewers. Editing and publishing an academic journal is nothing if not a collective endeavor. I am confident that I am handing over the helm to a worthy navigator in Mark Philip Bradley (Univ. of Chicago), who begins his own journey as editor in August and will oversee the September issue.

Editor’s Note: The name of Vusi Kumalo was originally misspelled in this article. It has been corrected.

Alex Lichtenstein is editor of the American Historical Review.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.