“Wondering What to Do with Your BA in History?” is one of the AHA’s most popular publications. The AHA Today post first appeared in 2010 and attracts thousands of page views per month. The continued popularity of this post and others in the blog’s “What to Do with a BA in History” series shows a real thirst for information on what history graduates can do with their degrees. While AHA Today regularly features former history majors reflecting on career paths in nursing, communication, and engineering, they represent only a fraction of history majors in the working world.

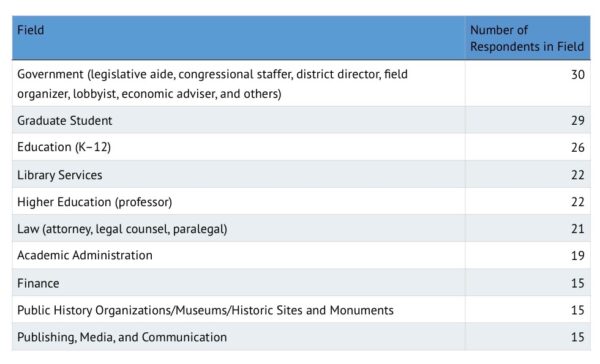

Fig. 1: Distribution of most common areas of employment for respondents who provided an occupation.

To get a broader sense of how history BAs are using their degrees, in fall 2016, the AHA released a public questionnaire for history BAs called “Why Study History?” The questionnaire gathered a wide range of reflections on how the skills and habits of mind developed as a history major influence careers and personal lives. The survey’s goal is to get the best of both worlds: real career trajectories and useful anecdotes from history BAs. The questionnaire is still live, and as the responses continue to come in, the AHA hopes to use them to reveal trends that can help direct its advocacy on behalf of the history major. The AHA’s Teaching Division will also use the information to inform its efforts to reverse the trend of declining enrollments in history, its focus for the next three years.

The responses collected so far reveal what over 350 history BAs think about their choice of study and how it has (or has not) contributed to their career trajectories and their views of themselves as individuals and citizens. Responses reveal that history majors work in a wide range of fields, from software design to journalism to insurance. Furthermore, respondents articulate the influence their degree has had, whether in the skills they use on a daily basis or the way they approach the world around them.

Methodology

The survey intentionally gathers qualitative data, which makes analyzing responses for overall trends a necessarily inexact process. It gives respondents the choice to answer 4 out of a set of 10 questions designed to prompt reflections on the value of undergraduate history education in their lives and careers. The survey also asks for recommendations on how undergraduate institutions might better prepare majors for a wide range of postgraduate paths. Some questions are fairly straightforward (“Are there specific skills that you use in your day-to-day work that you learned or developed in your history courses?”); others were designed to elicit responses to common concerns about majoring in history (“What advice would you give students who love history but worry that it won’t lead to a good job?”). All questions are free response.

The results represent trends that emerged from a subset of 200 responses selected at random from the total. These responses were analyzed for similar keywords and sentiments. The AHA intends to regularly re-examine responses as more people answer the questionnaire, and to continue to shape its strategy by listening to this feedback.

The Results

Questions of possible careers for history majors frequently presage hand-wringing over “what to do” with the history degree. The wide range of fields in which our respondents found employment provides evidence to assuage those concerns. Behind the top 10 fields of occupation (fig. 1), the next most common occupational areas are technology (software development, web design, and product management), nonprofit management and administration, and healthcare provision and research. Other occupations include firefighter (1), minister (4), social worker (3), journalist (2), and real estate agent (1).

Despite their occupational diversity, respondents named a consistent set of skills in answer to the question “Are there specific skills that you use in your day-to-day work that you learned or developed in your history courses?” The most frequent included research (52 percent), writing (45 percent), and critical thinking (40 percent). Close behind were analysis (39 percent), communication (20 percent), ability to consider multiple points of view (17 percent), and ability to take context into account (11 percent). These same skills are reflected in the newly revised History Discipline Core from the AHA Tuning project, which lays out a series of faculty-developed reference points regarding what an undergraduate history major knows, understands, and is able to do.

The survey also queried history majors about the impact of their degree beyond their professional life. Some of the most thoughtful answers came in response to the question “How has your major influenced who you are as an individual and a citizen?” The responses speak to the value of the undergraduate history major beyond the job market. Forty-two responses mentioned the value of approaching current events from a historical perspective; another 37 wrote that they are more civically “engaged,” “involved,” or “active” because of their history education.

History is often portrayed as both a springboard for further training (in history or another field) and as a complement to other areas of study. The survey responses affirmed this sense. Seventy respondents mentioned pursuing a secondary degree in areas like history, education, law, public history, business, and library and information science. Similarly, 89 respondents either double majored or took a minor in a subject other than history.

The results certainly skew toward those with enough enthusiasm about their undergraduate major to take the time to answer questions about it. Respondents were candid, however, about the challenges they faced, especially those who graduated during the years of the Great Recession. Several referred to the 2008 financial crisis and the challenge of graduating with a traditionally undervalued major as their impetus for getting a professional degree in something like business or management or simply finding employment without worrying about whether they were putting their degree to good use.

Despite these challenges, only seven of the random set of 200 respondents recommended others to not get a degree in history. Indeed, in response to the survey’s request to offer advice to students “who love history but worry that it won’t lead to a good job,” a few questioned the survey’s unqualified use of the term “good job” and encouraged students to define what that means for themselves. Thirty-six respondents echoed the advice to “do what you love,” but even more (45) encouraged current students to focus not on what it means to work as “a historian” but rather on skills that are transferable to other professions.

Respondents also encouraged students to learn to communicate the value of the skills they’re developing as history majors to others in different contexts. Some recommended that students double major or minor in another subject to cultivate a more diverse set of skills, pursue internships and concrete job experiences as undergraduates, and seek out alumni whose career paths interest them. These responses mesh with data from the Humanities Indicators project, which shows that earnings for humanists dramatically increase among those with secondary degrees.

Overall, the responses of the survey reaffirm widely held beliefs about the value of a BA in history—that history majors are employed in a wide variety of occupations, that studying history provides an entryway to a variety of fields of study and industry, and that history majors value and contribute to civic life. The AHA will use this information to update its online resources aimed at history majors and work with departments to develop strategies to address the recent decline in majors. To find existing resources, visit historians.org/why-study-history and historians.org/careers-for-history-majors. The survey is available at historians.org/history-ba-survey.

Some Responses to “Why Study History?”

I advise construction companies on purchasing and implementing enterprise software systems. I research products as well as the market, and present in writing and in person facts and analysis. I often have to make judgment using limited facts while avoiding biases. This is not at all far from what I did as a history major writing term papers!” Towner Blackstock, principal at Blackstock Consulting

“I never lost the sense that writing—I was a journalist and foreign correspondent for the New York Times for nearly three decades—demands a grasp of historical context in order to make intelligent sense of current issues anywhere and everywhere.” Barbara Crossette, United Nations correspondent for The Nation

“In clinical medicine, when one talks to a patient, we call it ‘taking a history.’ One has to take the information (not all of which is correct or relevant) and construct a narrative that makes sense.” Melinda Wharton, director of Immunization Services Division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

“Learning about the impact of human events big and small fueled my personal drive to become more civically engaged and to work for social impact.” Janet Arias-Martinez, associate director for alumni relations at the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute

“History provides the engine that powers your career. Critical thinking; knowing how to discover, collect, and correctly interpret evidence to make informed decisions; and being able to clearly and articulately convey complicated ideas, are all powerful tools for just about any industry.” Curt Johnston, director of education and workforce alignment for the Tennessee Higher Education Commission

“If you’re unsure of your career path, history will only benefit you. If you love history, then study it anyway because a ‘good’ job is about passion, not a paycheck.” Tim Anderson, firefighter with the Philadelphia Fire Department

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.