This article is part of the “Who Owns History?” forum (four articles, three of which appeared in the October 1996 issue of Perspectives).

History has been controversial since the days of Thucydides, but the quarrels that have taken place during this last decade of the 20th century have seemed particularly sharp, and the stakes notably high. The United States Senate has voted about the content of high school history courses. Public arguments have erupted over historical theme parks. And arts faculties have become polarized about what should be read in introductory history courses.

Professional historians make strong and serious claims here, and well they should. By “professional historians” I mean those who acknowledge a range of criteria in regard to evidence—what constitutes accurate and meaningful evidence; which modes and categories should be used to analyze it; which explanations, interpretations, and forms of exposition are acceptable; and where we should argue about and revise our picture of the past. Professional historians disagree today, for example, about the importance of climate in change or cultural style, but they agree that astrological explanations are not acceptable. I want to pose three questions in this paper about the ownership of history and end with a query about the concept of ownership as a metaphor for the work of reconstituting the past.

Do People Own Their Own History?

First of all, do people own their own history and, if so, are they its sole owners? By “people” I mean any group that recognizes a boundary of identity or comes to recognize a common past. The claim to possess is made not only by underdogs or suppressed groups. Established national traditions resent interlopers and defend their turf against, say, immigrant scholars who allegedly cannot seize the meaning of the American past or Americans who allegedly cannot sense the specialness of male-female relations in France.

The classic case in the current debate has been about groups silenced by some form of domination, who have perhaps lacked access to materials from which to build a historical account and who have surely been impatient when their past has been ignored or dismissed as unimportant or, in their view, misrepresented in existing historical publications. Such impatience is not new. Roy Foster tells us that 19th-century Irish writing was full of accusations against English historians: A. M. Sullivan’s Story of Ireland of 1867 proclaimed that Irish history “must not be absorbed into England’s corrupt narrative, substituting ‘her history of falsehood, rapine and cruelty for ours of faithfulness, noble endurance and morality—giving us the bloodstained memoirs of her land and sea robbers in place of the glorious biographies of our patriots and our saints.’”1 Decades of Irish historical inquiry were impelled by the desire to right this record.

The fruits of seizing and recording one’s own history have been double. For the group itself, there is an affective-political gain in enablement and a deepened sense of identity. As civic humanists in 15th-century Florence and royal humanists in 16th-century France rejoiced in establishing historical paradigms independent from Rome or a Germanic empire, so the historians within contemporary postcolonial societies and gender, diasporic, and ethnic communities take pleasure from the same process. No simple consensus emerges in these new histories, for disagreements appear early about the character of the group’s past. In historical writing about women, for instance, there was a rift from the beginning between books that stressed women as actors in family economies and those stressing the culture of the women’s world. In the histories written in India since independence, there is a rift—partly generational—between historians who take “the Indian nation” as their unit and those who insist on the diverse components in the past of the Indian subcontinent. A sense of identity is nourished not by simple boosterism but by important shared quarrels. The other benefit of seizing one’s history is a scholarly one. The findings unearthed in the enthusiastic pursuit of sources and the rethinking of categories, causes, and periodization that may follow are valuable for the group and beyond.

Thus, we respect the claim of groups, our own and others, to tell their own story. But is this a claim to sole ownership? To private property in textbooks, classrooms, and publications? I think not. Such a claim is not possible to sustain, since persons belong in fact to multiple groups and rarely have single identities, and published histories ordinarily seek multiple audiences.

Further, such a claim is not desirable to sustain, for there are advantages that come from external perspectives, from the insights of outsiders. The historiography of religions provides a good example of the advantages to be gained from outside perspectives. Back in the 1930s—and, indeed, even when I was a graduate student in the 1950s—much religious history in the West was confessional: Protestant history was written mostly by Protestants and published in Protestant periodicals; Catholic history mostly by Catholics for Catholic periodicals; Jewish history mostly by Jews for Jewish periodicals. Members of other religions appeared in these scholarly studies as enemies, persecutors, heretics, or as the occasional tolerant friend. Reshaping the contours of religious history was primarily the work of secularists determined to understand religion rather than demolish it, and of committed ecumenists. In France, Lucien Febvre played this role with Martin Luther. Un destin (1928), Le problème de l’incroyance au XVIe siècle (1942), and various articles published in nonconfessional periodicals, such as the Revue de synthèse historique and the Annales.

Here, too, the fruits are double. There is an affective-political gain once again. We grow not only through the deepening of self-identity, but through the discovery of difference and the perception of likeness in the strange. Our powers of empathy are stretched, our understanding widened. This has been a project of written history since Herodotus, even if he would not serve as our precise model. There is also a scholarly gain in collaborative and critical enterprise across boundaries of interest and knowledge. Team-teaching would seem advantageous for this purpose. Decades ago, a visit to India helped the English historian Eileen Power understand the Middle Ages, so she said. Those same centuries are cast in a new light today when Satish Saberwal writes of his observations in “On the Making of Europe: Reflections from Delhi.”2

Does the West Own History?

To pose a second question, does the West own history? That is, must the subjects, concepts, categories of analysis, and narrative models emerge from Western historical writings in order to count as “real” history? The major current conflict in North America swirls around Western civilization courses and their relation to “world history” and world history courses. At issue have been the efforts, in our postcolonial and post–Cold War decades, to make Western civilization courses more comparative and expansive or to replace them with world civilization courses. Historical exposition keeps moving: why always tell exactly the same story with the same vantage point, the same genealogies, the same trajectories of argument?

The vociferous critique of these efforts has been impelled partly by a nativist “middlebrowmanship,” as though it were better for students to know less, not more, and partly by an excessive rigidity about texts. Every teacher knows that one need not and sometimes should not assign exactly the same readings in the same order every year. If an important book is skipped one year, it can be picked up in another year or in another course. Meantime, space can be created for renewing the meaning of Augustine’s Confessions (to cite a contested example) by pairing it with a conversion autobiography from a different context.

The critique of the transformed Western civilization courses seems especially driven by a narrow boosterism, a sense that the Western past must always be upbeat. This is an odd demand when we recall that boosterism is not a substantial feature of the Western historiographical tradition. For Augustine, the City of God was glorious, but the City of Man was one disaster after another. For Thucydides and Machiavelli, the political past was not fine and dandy; they were writing to find out what went wrong. Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was upbeat neither about Rome nor about Christianity. Vico’s celebrated New History viewed the past in terms of cycles, not progress.

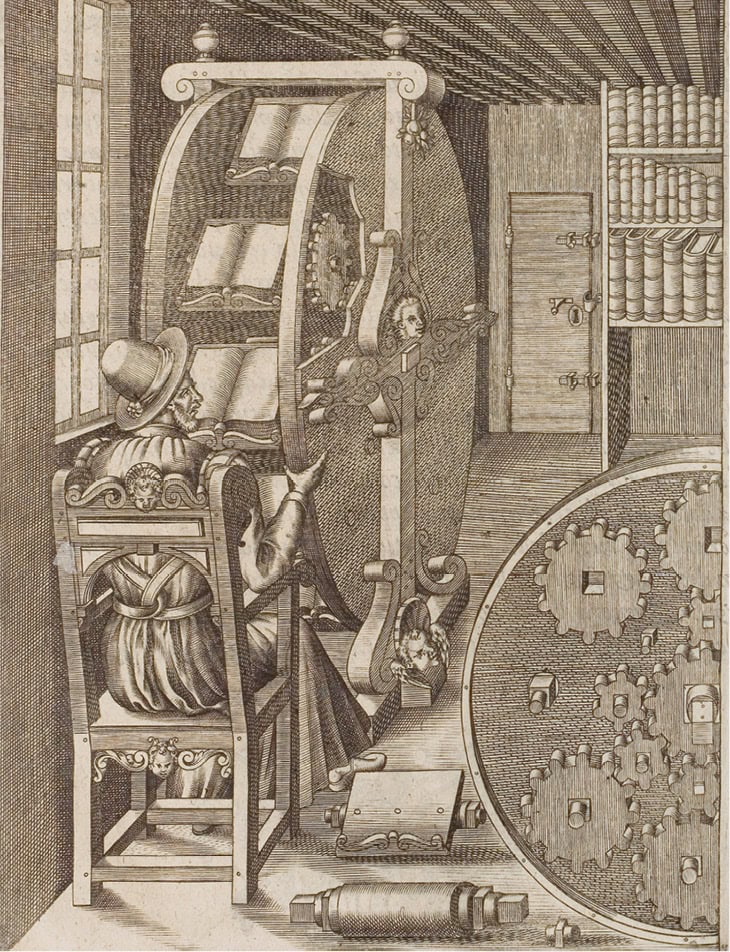

Moreover, the comparative perspective has been one of the best legacies of the Western tradition. Think of Fra Bernardino de Sahagun, recording Aztec lore in the 16th century in both Aztec and Spanish. Think of Michel de Montaigne’s “Des Cannibales,” where the songs of the Brazilians remind him of the songs of Gascony, the violence and warfare along the Amazon River is compared with that along the Loire, Seine, Rhône, and Saône. As Montaigne affirmed, the expansion of knowledge beyond our familiar borders brings us delight, teaching us simultaneously about ourselves and about others.

Despite the hostile critiques, world civilization courses are being developed across America. We should just get on with them, while being attentive to the genuinely important challenges that they pose. How do we give due emphasis to both genealogical and comparative perspectives? If the students are reading excerpts from Ibn Khaldoun’s Muqaddima (Prolegomena), then how do we find time both to show the place of his theories on the rise and fall of dynasties in the Arab debate of his own day and to compare his historical vision with that of other societies? If the students are reading excerpts from John Locke’s Second Treatise, then how do we weave together the story of rights and political contract as told in Europe with a cross-cultural examination of political theory? Perhaps one solution would be to assign texts in pairs, each pair illustrating dialogue within a society or polity while remaining available for comparison with a pair from without.

A more difficult problem is overall narrative. “The rise of the West” cannot contain or account for all the elements and motifs in a decentered world history. Steven Feierman has urged us to think about how to accommodate narratives originating in Africa with those originating in Europe.3 Stories of marriage and the struggle for political dominance need to be entwined with stories of the Atlantic slave trade and market development in an example from southern Africa. Combining diverse narratives does not provide a simple substitute for a single thread, but it is a start in the right direction.

Such issues are important not only in introductory world history classes, but also in the specialized local or regional history courses that follow. We should not continue to teach them as we always have, but find appropriate ways to introduce non-Western perspectives into them. In my course in early modern French history, introducing Amerindian perspectives along with French perspectives has deepened our understanding of major events; the Code Noir on slavery in the Caribbean turned out to be as important as the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the Royal Academy of Sciences in conceptualizing the world of Louis XIV.

Do Professional Historians Own History?

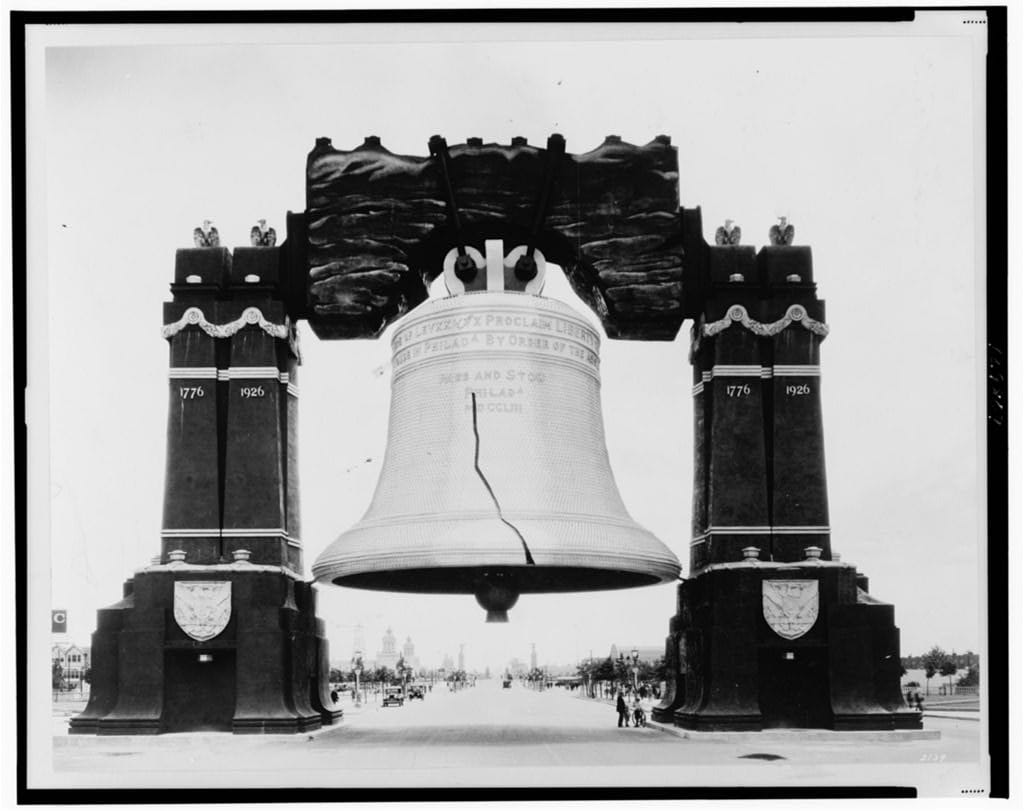

If the West does not own history in the classroom, do the professors who teach there nonetheless own history as against a larger nontrained public? That is, do historians own history? We have a very strong interest in the telling of history, but our ownership is not private, nor can we rightly claim an absolute monopoly. There are multiple impulses that move people outside the profession to learn about and recount the past, starting with curiosity about family and locality. And there are numerous settings outside the classroom and university library where the past is thought about and represented: battle reenactments, city festivals, movie theaters, TV, museums, theme parks. The negative features of such recountings of history have been noted: a nostalgic prettification of past events all the way to outright concealment and falsification for the sake of some narrow interest. Let us distinguish the private concept of “heritage” from the rational scrutiny of “history,” David Lowenthal enjoins us in his newly published study.4

But there are positive features as well in the nonprofessional look at the past. Raphael Samuel has stressed the advantages of reaching large publics, and with pasts that are not always so sweet and palatable. An example is a New York Times story from Noblesville, Indiana, where a local resident found a 1920s Ku Klux Klan membership list in an old trunk in his barn. Now in the hands of the Hamilton County Historical Society, the list has stirred up debate about the past throughout the community and beyond.5

The historian should welcome historical inquiry beyond the profession, engaging with it critically whenever needed and facilitating constructive research. After all, there is no absolute difference between the ways of seeking evidence and revising and checking views about the past in and outside of academe. And we, too, can be vulnerable to nostalgia and private interest. At best, nonprofessional history has much to teach not only its practitioners and their publics, but us: the questions asked about the past by people with training other than our own—the things they notice in the evidence—can be startling and enlightening. At worst, nonprofessional history leads to vigorous public debates. The controversy over the Smithsonian Institution’s proposed Enola Gay exhibition at least prompted people to ask themselves how and where the past should be represented. An even more productive debate took place in Canada in 1992–93 around the television documentary The Valour and the Horror, watched by more than 4 million people. Canadian airmen from the World War II bomber command, television journalists, newspaper reporters, professional historians, judges, ombudsmen, and members of Parliament argued back and forth about what should be said publicly about Canadian participation in World War II. History in this instance was not congealed and distant, but open and deeply important.6

Is the Metaphor of Ownership Valid in Regard to History?

Throughout this inquiry into the question of who owns history, the goal has been to open history even while insisting on the importance of the skills and questions of our craft. Private ownership has been found wanting at every turn. But perhaps the real stumbling block is the metaphor of ownership: even in its collective form, it does not seem right for our enterprise. An adage from the classical and medieval West adjured “Knowledge is a gift of God, whence it cannot be sold.” It seems to me that history is a gift from our predecessors, our forebears, who were actors in it or recorders of it. It is a gift we must work to receive, but it cannot be owned. There are always multiple claims to it. It is a gift that can survive only through debate. As professional historians, we recognize these multiple claims even while insisting on practices that acknowledge the rules of evidence and the responsibility to tell the truth as best we can. What we pass on to those we teach must come not as a patrimonial bequest with strings attached, or as some kind of strict settlement or entailment of ideas, but as a free gift of expanding evidence and actors, of vigorous discussion about the issues and meaning of the past, and of common loyalty to understanding that past to the best of our ability.

Notes

- Roy F. Foster, The Story of Ireland, An Inaugural Lecture Delivered before the University of Oxford on 1 December 1994 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), pp. 11–12. [↩]

- Satish Saberwal, “On the Making of Europe: Reflections from Delhi,” History Workshop Journal 33 (spring 1992): 145–151. [↩]

- Steven Feierman, “Africa in History: The End of Universal Narratives,” in Gyan Prakash, ed., After Colonialism: Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacements (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1995), pp. 40–65. [↩]

- David Lowenthal, Possessed by the Past. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (New York: Free Press, 1996). [↩]

- Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory (London: Verso, 1995). Dirk Johnson, “Old List of Klan Members Recalls Racist Past in an Indiana City,” New York Times, 2 August 1995. [↩]

- Graham Carr, “The Rightful Past: The Valour and the Horror and the Authority of History,” paper presented at the Biennial Conference of the Association for Canadian Studies in the United States (Seattle, Wash., 15–19 November 1995). [↩]