Several months ago, the AHA released “Where Historians Work,” a series of interactive visualizations created as part of our ongoing effort to collect measurable data about the career paths of history PhDs. Since then, thousands of people have used the visualizations to get a sense of the rich variety of jobs that historians find after completing their doctoral education.

“Where Historians Work” can also provide a fascinating rabbit hole for curious historians. Feedback from users suggests that one of the most common things people do with the data is to try and “find themselves” in it, that they sift through the visualizations to discover where their career fits into the bigger picture of PhD employment. Many are simply curious, wondering how many of their colleagues found work in government or at universities with profiles similar to theirs. In fact, finding yourself in the data is a great way to engage with what is the largest available study of career outcomes in the discipline. Here are some pointers on how to bring the data to life.

Background

You’ll find it’s easier to navigate “Where Historians Work” if you have a basic sense of what the data behind the visualizations is and what kinds of stories it can tell. Quantifiable information about the career paths of history PhDs is central to the AHA’s ongoing Career Diversity for Historians Initiative. To date, the AHA has published two large datasets documenting the careers of history PhDs. The first, “The Many Careers of History PhDs,” by L. Maren Wood and Robert B. Townsend, drew on a random sample of 2,500 history PhDs earned between 1998 and 2009. Then, in late 2016, we published “Where Historians Work,” the initial fruit of an even more ambitious effort to quantify the career outcomes of history PhDs and to make the data more interactive than ever before.

“Where Historians Work” contains information about the current careers of just over 3,250 PhDs. The data, however, is not comprehensive. It currently includes those who earned their PhDs between 2004 and 2013, and only from 34 of the 165 history PhD programs in the United States. (A full list of schools, selected to provide a wide cross-section of the academic landscape, is available on the second slide of the visualization). Later this year, the AHA will release data on the complete cohort of PhD graduates from 2004–13 and on the remaining 131 PhD-granting history departments, providing a comprehensive quantitative picture of early and mid-career historians.

“Where Historians Work” is based on data gathered by the AHA. We regularly receive bibliographic information about completed dissertations, and therefore completed PhDs, in history from departments for our directory. This list of completed dissertations is the starting point of our data collection, but the work of discovering where PhDs are currently employed is done in-house by AHA staff using publicly available resources such as employer websites, LinkedIn, and social media to identify the employment status and position of history PhDs. Using these sources, we are able to identify the occupations of 95 percent of those who earned their degrees during the 10-year period we have examined.

The Data

“Where Historians Work” includes history PhDs earned between 2004 and 2013. We picked this date range intentionally. By focusing on PhDs who are at least three years removed from their degree, we are giving them some time to settle into a career. This allows our data to reflect career outcomes rather than someone’s first, possibly temporary, job. Our data, unfortunately, is not longitudinal, and thus provide only a snapshot of people at a discrete moment of their professional lives rather than suggest career trajectories.

With over 3,000 PhDs from nearly three dozen institutions, the data set is large enough, however, to permit some generalizations about career outcomes. It is important, though, to note that “Where Historians Work” is still in its beta phase, pending full collection of data. (Once complete, the AHA will introduce a revised and expanded range of visualizations.) Even so, it provides a comprehensive picture of where historians work and has raised important questions about the relationship between graduate education and the careers of history PhDs.

“Where Historians Work” is a series of seven visualizations, some quite straightforward, others a bit less so. Collectively, they make it possible to see the career outcomes of historians from a variety of new perspectives ranging from the geographical disbursement of PhDs across the United States and the career paths of historians by area of subject expertise. Many of the slides are interactive, allowing users to narrow their searches by gender and to change the range of years represented on the slides. These features give you the chance to see how gender and cohort year shape the careers of historians.

Digging In

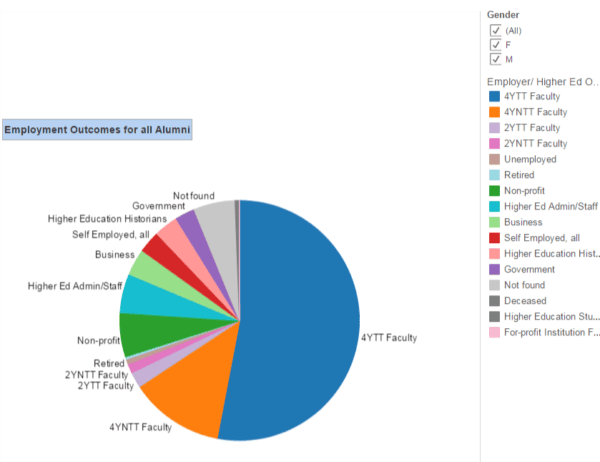

Three slides should be of particular interest to people who want to find out more about the types of jobs historians get. The first chart in the slideshow, labelled “Employment Outcomes for All Alumni” (fig. 1) provides an aggregate picture of the major sectors of employment for historians. This is, in some ways, the pivotal slide of the series because of how clearly it shows one of the major points of the AHA’s Career Diversity initiative—employment beyond the tenure track is a normal outcome for history PhDs.

Because it focuses on the big picture, it is not the best place to begin digging into the details. It’s much easier to find specific occupations using later slides in the series, particularly the third and fourth slides, which group occupational data into two broad categories that are then broken down further: primary employment as a teacher at a college or university, or employment beyond the professoriate (either within or outside the academy).

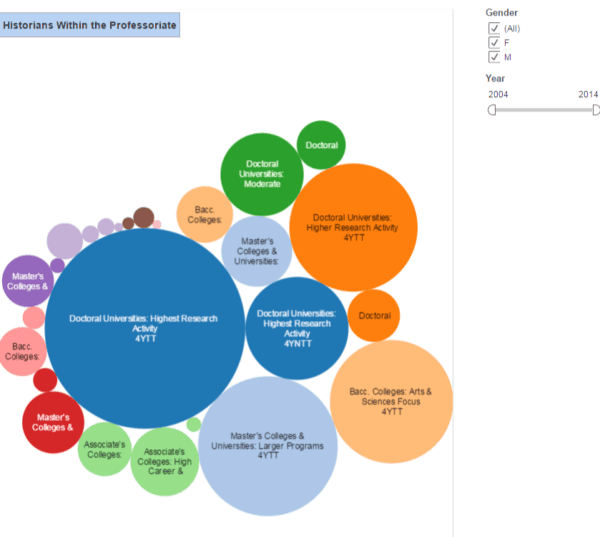

Fig. 2: This slide from “Where Historians Work” shows broad array of postsecondary teaching work that historians engage in.

The broad array of work in postsecondary teaching is reflected on the slide labelled “Historians within the Professoriate” (fig. 2). This slide includes only PhDs who hold teaching positions, on or off the tenure track, at postsecondary institutions, and the relatively smaller number of those working as postdoctoral scholars. The many bubbles here vividly represent the highly diversified landscape of higher education in America: R1 universities, comprehensive teaching universities, small liberal arts colleges, art schools, law schools, and community colleges. Most of these jobs are in history departments, but historians also find faculty positions in law, religious studies, and a variety of other academic departments.

One of the remarkable successes of our data collection efforts is that it makes it possible to quantify and characterize the careers of the approximately 25 percent of history PhDs who work beyond the professoriate. They are represented on the third slide of our visualization (fig. 3), “Historians beyond the Professoriate.”

Fig. 3: The third slide from “Where Historians Work” visualizes the careers of the approximately 25 percent of history PhDs who work beyond the professoriate.

This slide captures the many types of jobs historians find besides teaching at the collegiate level. Many of these historians find careers as educators, working as administrators in colleges and universities, and teaching in secondary schools (primarily at independent schools). A large number work as historians, a category that encompasses postdocs, researchers and consultants, and historians employed at museums, cultural institutions, or the government.

Collectively, about 53 percent of historians working beyond the professoriate find employment in these types of jobs. The remaining 47 percent also have extremely diverse professions—CEOS, managers, marketing and public relations professionals, fashion designers, farmers, translators, lawyers, producers and directors, librarians, and writers of all types. If you have developed a career as one of these, you may literally be able to “find yourself in the data,” particularly if you are one of the 164 history PhDs in the dataset who work in a career represented by fewer than 10 historians.

Even in beta release, “Where Historians Work” provides an intricate view of the broad array of the careers of history PhDs. It’s also a perfect forum for practicing the quantitative literacy skills that are increasingly important to early career historians navigating the diverse career options available to them. So, take a stab at diving into the data rabbit hole and let us know what you find!

“Where Historians Work” Twitter Chat on July 18

Got questions about the careers of history PhDs? Join the AHA’s Emily Swafford (@elswafford) for a Twitter chat on “Where Historians Work,” our groundbreaking database of career outcomes for PhDs. Ask Emily questions and share your thoughts about this new tool at #WhereHistoriansWork on July 18th, 2:00–3:00 PM EST. Direct-message questions to @AHAhistorians or email them to skingsley@historians.org if you prefer submitting them privately.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.