For many concerned Americans, the Trump administration’s seeming contempt for rules-based policies has been a source of deep anxiety. Democrats, in particular, have railed against a president they maintain is “actively” destroying “the rule of law he claims to be restoring.” From selectively complying with federal court orders to enacting arguably “rogue” immigration enforcement operations, customary rules no longer appear to apply.

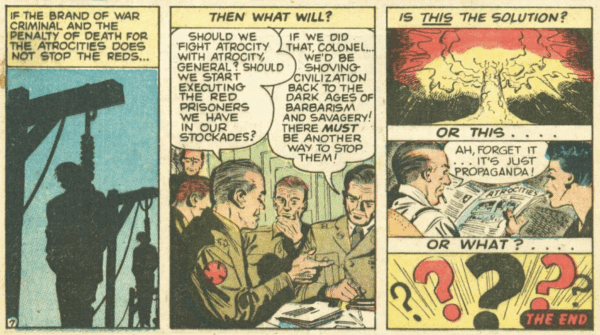

From the highest levels of US government to comic books, the early Cold War period had Americans debating the ethics of warfare in the face of communism. “Atrocity City,” War Adventures on the Battlefield no. 2, June 1952, Animirth Comics, Inc.

Nowhere is this more clear than in the nation’s military policy, especially at a moment when the commander-in-chief has threatened a land invasion of Venezuela and his secretary of defense allegedly ordered US military forces to “kill everybody” aboard a suspected drug vessel.

These actions, however, should not surprise given the administration’s martial rhetoric over the past few months. In what the New York Times deemed an unparalleled politicized “lecture” to senior-ranking US military officers, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s late September speech at Quantico, Virginia, raised deep concerns over the nation’s current state of civil-military relations.

While critics ridiculed the secretary’s narrow emphasis on “wokeness,” physical fitness, and personal grooming standards, perhaps the lecture’s most ominous portion was the condemnation against “stupid rules of engagement.” Leaning into his self-proclaimed warrior ethos, Hegseth shared that senior officers no longer would be handcuffed by “politically correct and overbearing rules of engagement, just common sense, maximum lethality and authority for warfighters.”

Though many Americans were taken aback by the secretary’s comments, there are clear Cold War analogies to such bellicose thinking and to the sometimes-heated debates around the ethical conduct of American servicemembers during times of war.

In 1954, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff developed its first common set of modern rules of engagement for regulating wartime violence, fearing the consequences of unintended escalation of hostilities in the atomic era. That same year, however, President Dwight D. Eisenhower commissioned a panel to study the effectiveness of the Central Intelligence Agency’s covert activities that cast doubt upon such rules. The study proceeded under the direction of retired General James Doolittle, who had gained fame during World War II leading a daring B-25 aerial raid against Japan in April 1942.

Finalized in September 1954, “The Report on the Covert Activities of the Central Intelligence Agency” left little doubt about the supposedly existential threat facing the United States. To Doolittle and his team, Soviet-inspired communism was a “fundamentally repugnant philosophy” at odds with “long-standing American concepts of ‘fair play.’” The panel then suggested that any naivety in confronting this “implacable enemy” bent on “world domination” jeopardized US national security. As Doolittle’s panel surmised, “There are no rules in such a game. Hitherto acceptable norms of human conduct do not apply.” If the United States was to survive, then the CIA had to engage in activities “more ruthless than that employed by the enemy.”

These fear-based conceptualizations of a savage, inhuman enemy who didn’t play by the rules echoed in policy documents throughout the early Cold War era. Just two months after Doolittle rendered his report, Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson, in a memo to the National Security Council, depicted communists as seeking “ultimate world domination, using armed force, if necessary.” To accomplish such a global aim, the enemy was surreptitiously engaging in “efforts to infiltrate, subvert and control” noncommunist governments around the globe.

Government officials portrayed the United States as facing an implacable and ruthless enemy, perhaps worse than the Nazi regime.

In these fear-inducing narratives, government officials portrayed the United States as facing an implacable and ruthless enemy, perhaps worse than the Nazi regime defeated less than a decade earlier. As Eisenhower himself noted in a year-end National Security Council meeting, even “Hitler was too horrified at the prospect of gas warfare” for fear of allied retaliation. (Apparently, the president deemed the German use of gas chambers at concentration camps like Auschwitz distinct from conventional “warfare.”) “There were some,” Ike said, “who believe that modern warfare imposes its own limitations.”

Of course, not all of Eisenhower’s martial predecessors would have agreed with the World War II allied supreme commander on this point. Did warfare, in fact, impose its own limitations? Perhaps not, and thus the need for more formal, violence-regulating protocols. During the American Civil War, for instance, Union Army leaders promulgated General Order No. 100, known as the Lieber Code, which required the ethical treatment of civilian populations and forbade the killing of prisoners of war. Lieber’s code became the basis for the Hague Convention of 1907, which among other wartime restraints, mandated that naval belligerents “take steps to look for the shipwrecked, sick, and wounded, and to protect them.”

But the questionable relevance of these wartime limits clearly was on the minds of senior Cold War policymakers as 1954 came to a close. The same month Secretary Wilson railed against the global communist “machinery” and its “war-making potential,” CIA director Allen W. Dulles warned of substantial Soviet advantages “in the field of integrated subversive warfare.” The problem came down to basic discrepancies in following the accepted rules—and, by extension, laws—of warfare. (US Code Title 50 governs the intelligence community’s operations.) According to Dulles, the Soviet system was “not subject to the pressures generated by democratic political and legal processes.” In short, the communists weren’t fighting fairly.

Against such an existential threat, one ideologically committed to global domination, it thus made little sense to follow dewy-eyed rules that might then lead to America’s demise. The stakes simply were too high. Nor were these policy prescriptions being considered in a vacuum. Popular culture mirrored debates over a rules-based international order.

In June 1952, while the United States fought a war against communism in Korea, War Adventures on the Battlefield comics published “Atrocity Story.” In the illustrated tale, wicked communists herd together Korean civilians and murder these “innocent victims of war” before turning their attention to captured American prisoners and “butchering” them as well. At story’s end, the comic invited its young readers to consider fighting “atrocity with atrocity” and “executing the red prisoners we have in our stockades.” A senior officer, however, voices his concern: “If we did that . . . we’d be shoving civilization back to the dark ages of barbarism and savagery.”

Looking back on this fraught Cold War moment, the Battlefield officer had a point. Wartime rules of engagement are not some “woke” constraint curbing military effectiveness as Secretary Hegseth would lead us to believe. As one legal expert rightfully notes, they are—and long have been—“the primary means of regulating the use of force in armed conflict.”

Indeed, the implications of unregulated applications of military force were evident throughout the Cold War era. By the time General Doolittle submitted his report to the president, the CIA already had assisted in coups overthrowing the governments in Iran and Guatemala, events that not only undermined legal clarity—as covert operations are inclined to do—but led to long-term instabilities that indelibly shaped regional politics in the Middle East and Latin America.

Wartime rules of engagement are not some “woke” constraint curbing military effectiveness.

Arguably, similarly enduring consequences could be felt, both at home and abroad, when American troops flaunted rules of engagement during the global war on terror, from the human-rights violations at the Abu Ghraib prison complex in Iraq to the killing of unarmed civilians in Afghanistan. According to one US Marine Corps officer, multiple violations of the rules of engagement in both Iraq and Afghanistan led to “negative and lasting impacts” on American counterinsurgency operations in those war-torn countries. Could it be that sensible rules assisted military commanders in accomplishing their mission rather than impeding them?

More recently, the Trump administration’s decision to employ US military forces for the targeting of alleged drug smugglers off the Venezuela coast, all while deploying an increased naval presence off the shores of Latin America and threatening outright invasion, has led numerous legal specialists to deem these “premeditated and summary extrajudicial killings illegal.” Secretary of State Marco Rubio has dismissed such legalistic hand-wringing, judging that the president had the authority “under exigent circumstances to eliminate imminent threats to the United States.”

War is chaotic and intended to be. But disdaining international rules of engagement and laws of warfare by inflating, if not exaggerating, threats to national security are counterproductive to US military operations and the troops who carry them out. Indeed, they put into question the very definition of “war.” Some critics, for instance, have argued that the Trump administration, in deploying National Guard troops to American cities, is fomenting civil war.

Depicting enemies, both foreign and domestic, as inhuman beasts who only respond to brute force and “maximum lethality,” whether during the Cold War or as Secretary Hegseth intimated in Quantico, leaves little room for commanders to use rules of engagement as an effective “control mechanism” for which they originally were intended.

And, perhaps most importantly, the men and women serving in uniform today need not be judged “politically correct” simply for being discerning managers of violence as they represent American society on the modern battlefield.

Gregory A. Daddis, a retired US Army colonel, is the Melbern G. Glasscock Endowed Chair in American History at Texas A&M University and author of Faith and Fear: America’s Relationship with War since 1945.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.