In the summer of 1991, I visited East Berlin, intent on photographing as much as I could of what remained of the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) physical iconography. As anyone who spent time in the eastern half of the city in the first year or two after reunification remembers, it was akin to a wilderness experience. The former Communist state was gone, while the new Federal Republic was only fitfully making its presence felt. Whole neighborhoods seemed absent of authority of any kind. I felt suspended in time, a condition that was curiously exhilarating (if sometimes threatening) while reminders of the bitter and recent past were everywhere. This was particularly so in the off-the-beaten-path locations where Communist authorities had installed memorials to border guards killed while on duty. The streets were empty, the buildings were desolate and still showed the marks of the fighting in 1945, and the few patrons I encountered in local taverns wanted nothing to do with a foreign interloper.

Commemorative marker for wall guard Peter Göring, Scharnhorst Strasse, August 1991.

But it was the memorials I managed to locate that made the greatest impression on me. Here was the detritus of a failed state, a discredited ideology, and an unwanted history. The most telling monument of all, the Berlin Wall itself, survives at several locations and in various configurations. Little reference is now made to its official GDR designation as the “anti-fascist protective barrier.” Antifascism was the legitimizing ideology of the East German state, and nowhere was it more in evidence than in the eastern half of Berlin. In its memorial program, priority of place went to members of the Communist resistance against the Nazi dictatorship, best materialized by the enormous bronze bust of Communist Party leader Ernst Thälmann that stands in the Prenzlauer Berg district. Well into the 1990s, on every August 18, Socialist Unity Party (SED) pensioners, GDR loyalists, and neighborhood residents gathered at the statue to commemorate the anniversary of Thälmann’s 1944 death in Buchenwald. Derelict for years, periodically cleaned of graffiti by local authorities, Thälmann’s statue remains an object of contestation, too large and too expensive to remove.

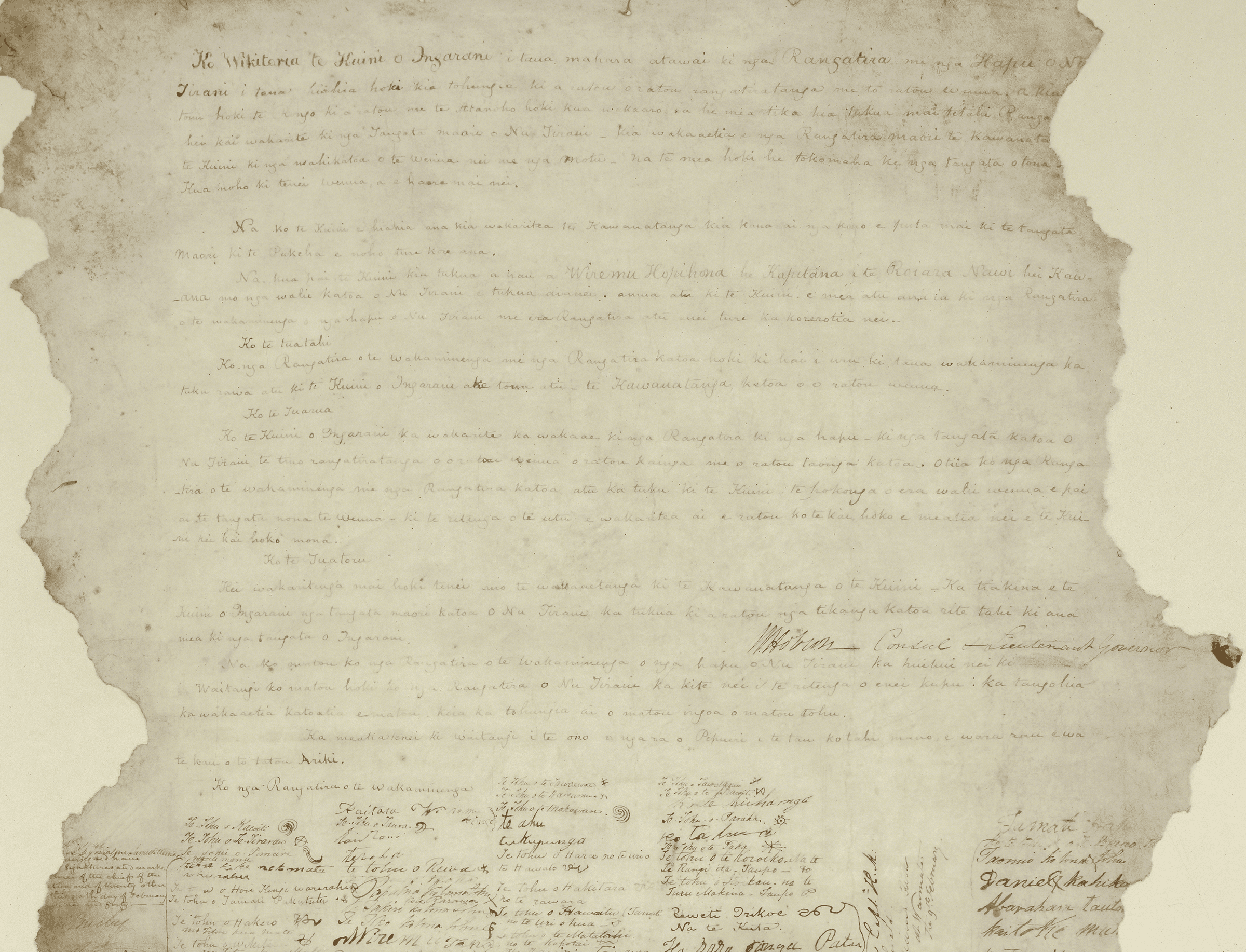

Other icons of the workers’ and peasants’ state were more rudely treated—none more so than the designated “hero-victims of the socialist frontier,” the eight border guards who died along the Wall between 1961 and 1989. These men died on duty, in some cases shot by those trying to escape and in at least one case in an exchange of gunfire with West Berlin police. The markers erected to honor them were among the first to be toppled once the Wall was opened. Because they looked like gravestones, when pried off their bases, these stone slabs formed an eloquent testimony not to the individuals they named but to the visceral hatred that the GDR regime had generated among its citizens, even as it sought to mobilize emotional support for its fallen heroes. Or the evidence I found may have been the result of random acts of vandalism, apolitical or not.

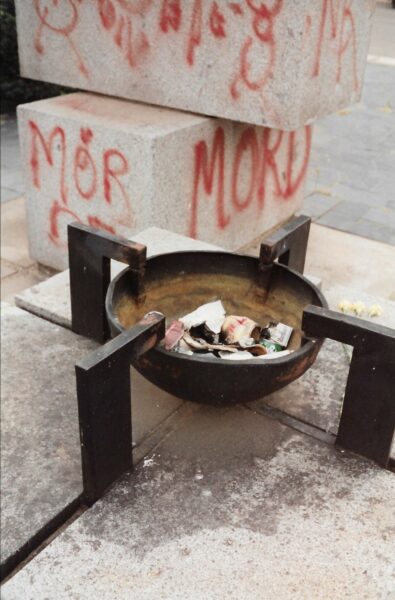

In contrast, the fate of the GDR’s central memorial to the guards was clearer. Erected in 1973 at Jerusalemer Strasse just across the sector boundary from the towering Springer Verlag building, this site was a favorite ceremonial destination for SED leaders. As such, it was an early target when the Wall came down. Parts of its inscription were chiseled away, what remained of the text was defaced with anti-GDR slogans, and the brazier meant to honor the fallen guards became, literally, a trash container. The entire ensemble was removed in the mid-1990s. Reinhold-Huhn Strasse, the street the Communists had renamed for one of the fallen guards, reverted to its previous name, Schützenstrasse. Superstar architect Aldo Rossi constructed a multicolor building complex nearby, and a once important GDR site was absorbed into the rapidly gentrifying district around what had been Checkpoint Charlie.

Here was the detritus of a failed state, a discredited ideology, and an unwanted history.

Through the 1990s, those who died trying to cross from East Berlin into West Berlin remained in the spotlight, as new memorials were erected, the border guards implicated in their deaths were put on trial, and the GDR leaders whose orders the guards had followed were similarly brought to justice. These trials usually resulted in convictions, but with shortened sentences due to health considerations or—in the case of the border guards—brief or suspended sentences. Few Berliners at the time, on either side of the former divide, found the verdicts satisfactory.

At the same time, the lengthy deliberations that preceded the construction of the official Berlin Wall memorial site were complicated by the question of whether the East German guards who died in their efforts to interdict attempted escapes should be included among the Wall’s victims. Ultimately, a compromise was reached: when the memorial was completed at Bernauer Strasse, north of the city center, a single separate marker acknowledged the GDR guards. Anyone looking for evidence of their commemoration by the GDR regime before the Wall came down will find nothing at the original locations, now long ceded to postunification construction, reclamation by nature, and the erosion of memory even among those who might be invested in remembering.

The SED memorial to fallen border guards, Jerusalemer Strasse and Reinhold-Huhn Strasse, August 1991.

For pragmatic rather than political reasons, the built legacy of the GDR cannot be entirely erased from the Berlin cityscape. Not for lack of trying, as the demolition of the GDR Foreign Ministry building in 1996 and the East German parliament house, the so-called Palast der Republik, in the mid-2000s can attest. Lost in the underbrush, so to speak, are the once visible traces of a political culture that was assiduously promoted for 40 years, even if it began to show signs of exhaustion toward the end. Only a footnote—if that—to the history of a failed regime and discredited ideology, the photographs I took in Berlin in 1991 might recall a brief period when, to recycle the timeless reference from Antonio Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, “the old is dying, and the new cannot be born.”

Inconsequential when compared to more famous examples of “monument cleansing”—the removal of Stalin’s statue from Heroes’ Square in Budapest in 1956, the dismantling of the Lenin monument in Berlin in 1992, the toppling of the Saddam Hussein statue in Baghdad in 2003, to name only a few—the consignment to the dustbin of history of the GDR guards who perished at the Berlin Wall should remind us of the fickleness of memory.

Reading the service records of the eight border guards who died at the Berlin Wall reinforces the belief that they too were victims, compelled by a governing system to accept roles whose alternatives were even less attractive. Testimony from former guards confirms their moral and psychological discomfort with contemplating, let alone executing, the “shoot to kill” order imposed on them, perhaps especially when the target was a fellow East German. The suspended sentences on those who were brought to trial reflect, even if subconsciously, the ambivalence their countrymen feel toward those they themselves may have been but for the vagaries of birth and geography.

Trash in the ceremonial brazier at the SED memorial, August 1991.

Twenty-five years since the publication of Brian Ladd’s The Ghosts of Berlin (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1997), scholarship on monuments and memorials in the German capital has become a minor industry. While small in comparison with the discussions of how the Holocaust is remembered, the memorial culture of the former Communist state has not been neglected, even as scores of street names, dozens of monuments, and almost all ideologically encumbered locations have been repurposed or simply effaced. Reflecting not only a continuing dissatisfaction with the social and economic consequences of reunification, a view of the past (Ostalgie) that is at least partly illusionary, and an alienation from the colorless politicians who today command the fortunes of the Federal Republic, the aspirational claims—however unrealized in practice—of the East German state exert an attraction that engages the attention of activists and academics alike.

The GDR’s memorial culture, like so many other aspects of East German history, remains an active subject for scholarly interpretation. Whether closely focused like Pertti Ahonen’s Death at the Berlin Wall (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011) or more expansively intended like Hope Harrison’s After the Berlin Wall: Memory and the Making of the New Germany, 1989 to the Present (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2019), the recent post-Wall scholarship reifies in print what has largely ceased to exist in fact. Almost lost in the increasing abstractions that shape these debates are the concrete objects—literally—that gave form to this contested memory.

Almost lost in these debates are the concrete objects—literally—that gave form to this contested memory.

Berlin today is much changed from the city I visited more than 30 years ago. Locations I photographed then are virtually unrecognizable, like the “death zone” between Potsdamer Platz and the Brandenburg Gate, at whose northern end the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe now stands and the onetime Marx-Engels Platz, now dominated by the reconstructed facades of the Hohenzollern Royal Palace. The transformation is most striking in the east, as even those memorials that have survived—such as the former Soviet cemetery in Treptower Park with its acres of graves and its colossal triumphant Red Army soldier—have fallen off most tourists’ itinerary. The practiced eye can still identify many markers from the past, although the ghosts that haunt them become ever more evanescent. Berlin is not alone in this characterization, but some of its ghosts are more fleeting than others.

Site of the Peter Göring marker, August 1994. James J. Ward

James J. Ward is professor of history emeritus at Cedar Crest College.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.