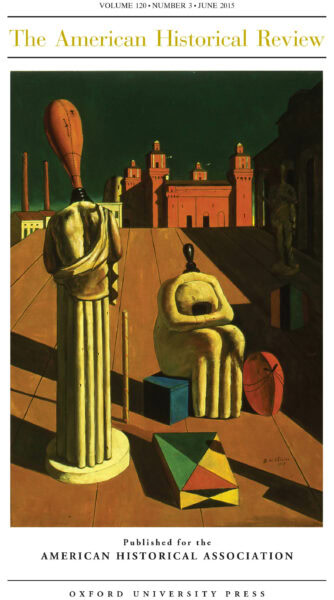

In “Retrieving the Lost Worlds of the Past: The Case for an Ontological Turn,” Greg Anderson shows how the conventional tools of historicist practice encourage historians to refashion the contents of non-modern lifeworlds to fit modern ontological presuppositions. As a result, he says, the very essences and foundations of past experiences become lost in translation. In this painting by the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, Anderson sees the conjunction in a single frame of disembodied elements from ancient, medieval, and modern worlds as a metaphor for the way our historicism translates the past. Using classical Athens as a case study, his essay suggests an alternative way to historicize the experiences of past peoples. To produce more ethical, more meaningful histories, Anderson says, we need to analyze each non-modern world on its own ontological terms, in accordance with its own particular standards of truth and realness. Giorgio de Chirico, The Disquieting Muses. Oil on canvas, 1947. University of Iowa Museum of Art, Gift of Owen and Leone Elliott, 1968.12. Used by permission of the University of Iowa Museum of Art.

When members receive the June issue of the American Historical Review, they will find two articles—one on ancient history, the other on the Caribbean in the 17th century—followed by an AHR Roundtable, “The Archives of Decolonization,” consisting of seven essays. Five featured reviews, all on World War I, precede our usual extensive book review section. “In Back Issues” offers readers a glance at issues from 100, 75, and 50 years ago.

In the first article, “Retrieving the Lost Worlds of the Past: The Case for an Ontological Turn,” Greg Anderson proposes an alternative way to historicize the experiences of non-modern peoples. Building on the claims of postcolonial and other critical theorists, he questions the ontological premises of conventional historicism, showing how the standard analytical approach unwittingly imposes modern ontological presuppositions regarding materialism, secularism, anthropocentrism, and individualism upon non-modern lifeworlds. The net result, he argues, is a disciplinary practice that systematically obscures extinct forms of subjectivity and sociality, agency and authority, freedom and equality, temporality and spatiality. To produce histories that are more ethical, more theoretically defensible, and more historically meaningful, he urges us to analyze each non-modern world in its own metaphysical environment, according to its own particular standards of truth and realness. To give his argument concrete form and to show how this alternative historicism might work in practice, he turns to classical Athens, his area of expertise, as a case study.

In “Discovering Slave Conspiracies: New Fears of Rebellion and Old Paradigms of Plotting in Seventeenth-Century Barbados,” Jason T. Sharples uses an investigation into slave conspiracy in 17th-century Barbados to examine how colonizers attempted to make sense of subject populations. When investigators in 1692 believed that they had uncovered a planned rebellion, they assessed the intended violence in a way that exaggerated the threat. In refashioning guiding concepts drawn from existing frames of reference for insurrectionary violence—most notably knowledge of slavery in ancient Rome and memories and expectations of Catholic violence against Protestants—and applying them to life in Barbados, they grappled with the unfamiliar in ways that betrayed the importance of analogical thinking. Sharples uses this case to examine the intersection of Barbadian social history and European and African discourses in the production of knowledge. His analysis suggests a model for how overlapping discourses can interact through nested operations of analogical thinking. By emphasizing the discursive creation of knowledge, his article contributes to recent debates over whether slaves intended to rebel in alleged insurrectionary conspiracies in colonial America and the early United States. It also sheds light on collective resistance more generally by identifying conspiracy scares and actual rebellions as distinct but related phenomena.

The AHR Roundtable, “The Archives of Decolonization,” presents seven essays that interrogate the special challenges of making history out of the decolonizing past in several different contexts. In her introduction, Farina Mir, a historian of colonial and postcolonial South Asia, places the somewhat recent interest in the archival sources of decolonization not only in the wider scholarly context of the history of decolonization, but also, more pointedly, in the contemporary understanding of this phenomenon as a process and not simply an event—not simply a “transfer of power.” As a “capacious” process, it largely shapes the world we live in, and its effects live on. But understanding it as a process and not an event only begins the interrogation of understanding it in all its varied forms and contexts. Like other contemporary approaches to history, this subject forces us to think about the question of scale. As Mir notes, “There is the broad and shared history of decolonization that spans empires and continents, and there are the local histories that simultaneously constitute it.” The six essays that follow, which she crisply summarizes, pursue their investigations on both of these scales.

In the first essay, “Looking beyond Mau Mau: Archiving Violence in the Era of Decolonization,” by Caroline Elkins, the author herself plays a central role in recovering an “archive of decolonization.” In the spring of 2009, five elderly Kenyans filed suit in the High Court of London against the British government for alleged colonial crimes perpetrated in the detention camps and emergency villages of Kenya during the Mau Mau Emergency (1952–60). Two revisionist works of history, Imperial Reckoning by Elkins and Histories of the Hanged by David Anderson, provided the evidentiary basis for these claims. Moreover, the authors served as expert witnesses for the claimants. Elkins’s essay recounts how the British government sought twice to strike the case out on legal technicalities, though it was ultimately settled in June 2013. Through legal discovery, the British government released 300 boxes of previously undisclosed files pertaining to Kenya. It also found some 8,000 files from 36 other colonies that had been similarly hidden since the era of decolonization. The implications of this discovery, and the resulting processes that unfolded in the High Court, are far-reaching for future historical writing on the end of the British Empire. Of greatest importance is the field’s newfound understanding of the scope and systematization of document destruction at the end of empire, the culling of the official archives in London, and the relationship between the destruction of minds and bodies in 1950s Kenya and the similar destruction and removal of archival evidence at the time of decolonization.

The next essay takes us to Algeria. In “’Of Sovereignty’: Disputed Archives, ‘Wholly Modern’ Archives, and the Post-Decolonization French and Algerian Republics, 1962–2012,” Todd Shepard notes that the French-Algerian “dispute” (“le contentieux”) over the archives of French-ruled Algeria has flared into public controversy at several moments since Algerian independence in 1962. A history of this conflict between former colonizers and colonized over where the contested archival holdings should be stored draws attention to national archives as key institutions of modern states, notably in how they authorize claims of sovereignty. Through their existence and functioning, they help constitute a state insofar as their workings offer proof that it is an emanation of its people, a nation-state, and thus modern. Shepard argues that focusing on archives as institutions helps explain why the dispute has had political repercussions on both sides of the Mediterranean, “shap[ing] historical production in ways far larger than missing documents—even in large numbers—can justify.” This history of the dispute also makes clear how much decolonization shaped the history of modern archives, especially the post-1945 shift from “archiving the state” to “archiving the nation.”

The next essay indeed takes us into an archive of a colonizing nation. In “Where Did the Empire Go? Archives and Decolonization in Britain,” Jordanna Bailkin delves into a series of recently declassified files at the National Archives in Kew in order to explore where the history of decolonization can be located within this vast collection. She hopes to spark new conversations about the sources we use to explore the decline and reconfiguration of imperial power. In particular, she asks us to consider the unexpected ways in which decolonization registered its presence in Britain—and in British archives. Mapping more precisely where and when the theme of decolonization shows up in the National Archives can aid us in understanding not only the unevenness of decolonization’s own historiography, but also some of the broader dynamics of secrecy and openness in Britain’s culture of information. Moreover, these sources can help us reevaluate the impact of decolonization on individual experience. Writing from a metropolitan vantage point, Bailkin focuses on a less expected element of the National Archives—the welfare files, rather than the Colonial Office or Foreign Office files—to see what they can tell us about a more diverse history of decolonization and its actors that extends beyond the realm of high politics into the familial, the social, and the intimate.

In “Black Holes, Dark Matter, and Buried Troves: Decolonization and the Multi-Sited Archives of Algerian Jewish History,” Sarah Abrevaya Stein returns us to Algeria, but with a focus on the French colony’s Jewish population. Amid the denouement of the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62), a variety of international parties, including officials in Israel, France, and Algeria, competed to micromanage, acquire, and steward documents pertaining to the small community of Jews in the Algerian Sahara. Looking back on the unique colonial history of southern Algeria, Stein’s essay reconstructs the ways in which French colonial classifications haunted the postcolonial era, continuing to affect Jews of southern Algerian origin long after the Algerian Sahara ceased to be home to Jews and Algeria became a sovereign nation. She also argues that in the era of decolonization, the struggle to control papers pertaining to Saharan Jewish history abetted a spectrum of local, communal, and national projects. Moving outward, the article meditates on what is unique but also what is generalizable about archives of the postcolonial era, suggesting that they are particularly multi-sited, yet political, contentious centers of conversation. Stein concludes her essay by exploring contemporary echoes of her case study apparent in the political intricacies that surround various extant and/or endangered North African and Middle Eastern Jewish archival collections.

The next essay remains in the Middle East but turns to Egypt. In “‘History without Documents’: The Vexed Archives of Decolonization in the Middle East,” Omnia El Shakry explores the idea of a “history without documents,” first by outlining the material inaccessibility of postcolonial state archives in the Middle East, and second by questioning the compositional logics of archival imaginaries of decolonization. In what ways, she asks, have historians remembered, forgotten, or appropriated the various intellectual traditions that belonged to the era of decolonization in the Middle East? By shifting our attention away from dominant and declensionist narratives of decolonization as a state-driven and secular political process so as to include members of the intelligentsia, social scientists, and religious thinkers, who are bypassed in or excised from traditional archives, she suggests that we might better see decolonization as “an ongoing process and series of struggles rather than a finite event, as regional as well as national, intellectual and cultural as well as political, and religious as well as secular.”

The roundtable concludes with an essay that looks at the archives of decolonization in an expected context. Ever since the Cold War imagining of a three-world planet, professional convention has excluded the United States from deliberations about decolonization. Breaking with this convention, H. Reuben Neptune, in “The Irony of Un-American Historiography: Daniel J. Boorstin and the Rediscovery of a U.S. Archive of Decolonization,” offers a radical recasting of the nation’s historiographical archives and, in particular, its classification of the scholarship of Daniel J. Boorstin. For more than half a century, Boorstin has been repudiated by nearly all students of US history as “the most egregious source of the pathetically patriotic consensus history-writing trend that supposedly swept the field in the decade and a half after World War II.” However, Neptune argues that Boorstin’s writing, read through the lens of decolonization, can be viewed as postcolonial historical scholarship about the US. Running through Boorstin’s work on the republic is a concern that traditional thought had failed even to confront, far less overcome, American subjection to the hegemonic liberal fictions inherited from Europe. Playing up problems, failures, and vices of colonial vintage, Boorstin’s narratives subverted prevailing patriotic history-writing that struck him as too enamored with the romance of national invincibility, or “omnicompetence.” Using an ironic mocking style of prose that has gone unrecognized by his professional detractors, Neptune writes, Boorstin rendered the North American republic “a lamentable and laughable postcolony.”

October’s issue will include articles on state violence in British India and the myriad uses and meanings of translation, an AHR Roundtable on “The Humanities in Historical and Global Perspectives,” and the AHR Conversation.

With this issue, we must say good-bye to several people who have helped to make this journal what it is. David Bell, Timothy Brook, Susan Juster, and Carol Symes are all cycling off the Board of Editors after serving us expertly for three years. Their successors will be announced in the next issue. Book review editor Allison Madar is leaving us for a tenure-track job in California. And Alex Lichtenstein will be finishing his term as associate editor. His successor is Konstantin Dierks, who served in that capacity in 2009–10 and as acting co-editor in 2010–11. But Alex will not be going far. In August he will step in as the AHR’s interim editor for 2015–16.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.