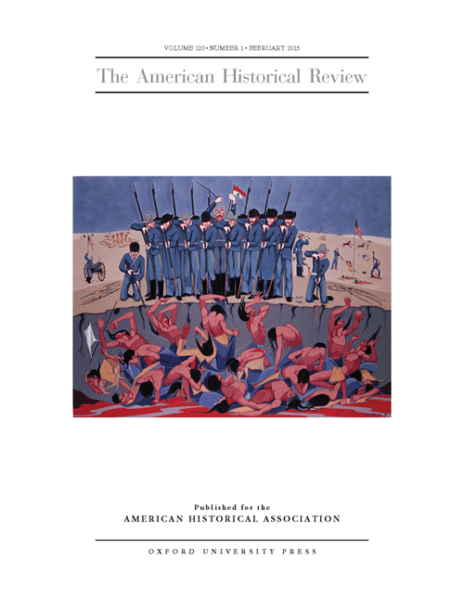

On December 29, 1890, for reasons that remain contested, the Seventh Cavalry Regiment of the US Army opened fire on some 400 surrendered Minneconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Several hours later, at least 200 Lakota lay dead or mortally injured. Of those killed, the majority were women and children. In “Reexamining the American Genocide Debate: Meaning, Historiography, and New Methods,” Benjamin Madley explores the question of whether Native Americans suffered genocide during the conquest and colonization of the United States and proposes new methods of inquiry that can also be used to locate and define other potential cases of genocide within and beyond the Americas. Oscar Howe, Wounded Knee Massacre. Casein on paper, 1960. Dwight D. Eisenhower Museum, Abilene, Kansas. Copyright © Inge Maresh. Used by permission.

When members receive the February issue of the American Historical Review, they will find Jan Goldstein’s Presidential Address and four articles on subjects as disparate as human-animal relations in Caribbean and South American history, the reception of an 18th-century book around the world, the debate over the genocide of Native Americans, and Nazi-Muslim relations in the era of World War II—a sampling of the rich range of today’s historical scholarship. They will also find, of course, our large book review section of more than 200 reviews, including seven featured reviews. “In Back Issues” offers readers a glance at issues from 100, 75, and 50 years ago.

Jan Goldstein’s Presidential Address, “Toward an Empirical History of Moral Thinking: The Case of Racial Theory in Mid-Nineteenth-Century France,” confronts the delicate problem of the historian’s moral stance when investigating an area in which the so-called verdict of history is loud and clear. Her case at hand is the fashioning of racial theories in 19th-century France among a group of intellectuals and writers, some well-known, such as Alexis de Tocqueville, Arthur de Gobineau, and Ernst Renan, and others less so. She strives to take us beyond mere condemnation and into a consideration of what she calls the “moral field,” configured by “lines of force”—a range of norms or sets of considerations—which guided their thinking. Importantly, and especially in this particular moral field of racial theory, she urges us to consider “thinking as practice, rather than thought as product.” Her account of these writers illustrates their practices by anatomizing the choices they entertained as they elaborated their views on race and racial concepts. Goldstein’s essay thus not only offers us a window into the intellectual culture of mid-19th-century France, but also suggests a model for thinking about race—or other morally vexed subjects—in other times and cultures.

In “The Chicken or the Iegue: Human-Animal Relationships and the Columbian Exchange,” Marcy Norton investigates animal “familiarization” among indigenous groups in the Circum-Caribbean and lowland South America over the longue durée from 1492 to today, with a particular emphasis on the periods following European contact. The Carib word and concept iegue refers to tame or familiarized beings (human and nonhuman alike). In using it, Norton provides insight into fundamental differences between European and Amerindian cultures’ ways of organizing interspecies relationships. Both historical and contemporary ethnography show how a wild animal—like an enemy or a spouse—becomes assimilated into a household and community as kin, or iegue. Unlike European livestock, it was anathema to kill or eat an iegue, though an untamed animal of the same species was eminently edible. Recovered histories of Amerindian familiarization, Norton argues, compel us to rethink conventional narratives of animal domestication, the origin of the European “pet,” and the environmental history of the Columbian Exchange. It contributes to a cross-cultural and trans-species history of subjectivity.

In “The Way to Wealth around the World: Benjamin Franklin and the Globalization of American Capitalism,” Sophus A. Reinert analyzes Franklin’s perhaps best-known text, his 1757 “Father Abraham’s Speech” from the final edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack, and maps its global diffusion up to 1850, demonstrating its hitherto unknown yet extraordinary popularity in the European world and, eventually, well beyond it. The text was doubtless one of the cardinal vehicles of a recognizably capitalist ethos in the modern world. Although Franklin’s rhetorical strategies proved extremely effective, Reinert argues that the aphoristic style of his piece failed to reflect the complexity of his political economy and the ethics of his economic vision. As he concludes, this is a legacy that continues to color our understanding of “American capitalism.”

Before contact, perhaps five million or more Native Americans populated what is now the continental United States. By the late 19th century, fewer than 250,000 remained. What caused this cataclysm? Diseases, colonialism, and war all played important roles, but was something more sinister also to blame? In “Reexamining the American Genocide Debate: Meaning, Historiography, and New Methods,” Benjamin Madley pursues these and other questions. Academics and others have long debated whether or not Native Americans, or any groups of them, suffered genocide during the conquest and colonization of the Americas. Madley first explores why the question matters to scholars, American Indians, and indeed all citizens of the United States before surveying the polarized American genocide debate as it applies to the United States and its colonial antecedents. But his essay also proposes new methods of inquiry—involving detailed case studies and a focus on statements of genocidal intent, massacres, state-sponsored body-part bounties, and mass death in government custody—that, he argues, will move the debate forward. Finally, Madley demonstrates these methods in two cases, those of Connecticut’s Pequot Indians and California’s Yuki Indians. He concludes by suggesting how this approach might be applied to locate and define other cases of genocide both within and beyond the Americas.

The last article in this issue is “Muslim Encounters with Nazism and the Holocaust: The Ahmadi of Berlin and German-Jewish Convert to Islam Hugo Marcus,” by Marc Baer, who aims to call into question simplistic renderings of the Nazis’ relationship to Muslims, complicate historiographical accounts of Islam in Europe by underscoring its diversity, and render more complex our understandings of Muslim-Jewish relations. He notes that research on Muslims in the World War II era has overwhelmingly looked at Muslims in the Middle East or those who were temporarily located in Berlin, focusing on Arabs, and indeed on a single Palestinian, the Mufti of Jerusalem, Al-Hajj Amin al-Husayni, whose notoriety has overshadowed the activities of all other Muslims in Germany and elsewhere. Based on an examination of the publications and archival records of the first Muslim communities in Germany, and the personal documents and private correspondence of their leading members, Baer focuses instead on an overlooked yet significant Muslim community, the Ahmadi, based in British India. In 1922, they established a mission in Berlin, which attracted German avant-garde intellectuals, partly through the promotion of conversion as a kind of double consciousness, the preaching of interreligious tolerance, and the admittance of homosexuals. A decade later, when German society was Nazified, the Ahmadi—unlike the other Muslims in Berlin—in one important instance thwarted the Nazi reign of violence. Despite accommodationist overtures to the regime, they saved the life of their formerly Jewish coreligionist Hugo Marcus, who was also a homosexual. As Baer concludes, this example calls into question the claim that Muslims shared a deep-rooted antisemitism with the Nazis.

April’s issue will include articles on medieval law, the Atlantic slave trade, revolutionary Cuba, and the intellectual background to human rights; an AHR Exchange on The History Manifesto; and the AHR Conversation.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.