Members should be receiving the February 2009 issue of the American Historical Review by the end of this month. It contains the presidential address, an article on business and governments in the early 20th century, and Part One of an AHR Forum on “The International 1968.” As always, these are followed by our extensive book review section, which includes several featured reviews.

Members should be receiving the February 2009 issue of the American Historical Review by the end of this month. It contains the presidential address, an article on business and governments in the early 20th century, and Part One of an AHR Forum on “The International 1968.” As always, these are followed by our extensive book review section, which includes several featured reviews.

February’s issue leads with the text of the presidential address delivered by the outgoing president of the American Historical Association, Gabrielle M. Spiegel, at the Association’s 123rd annual meeting in New York City in January. “The Task of the Historian” is an intellectual tour de force, offering an account of the emergence of poststructuralism as a central concern of historians in the last few decades, an account that is both sophisticated and timely. She situates its emergence in the wake of the Holocaust, which, for “second generation” intellectuals—that is, those who did not experience its horrors but had to reflect upon them nevertheless—created a rupture or absence that could only be filled with language. For these thinkers, however, language offered no stable meanings, no fixed representations, no direct access to this terrible past. Quite the contrary. Influenced by the “linguistic turn,” many historians subscribed to the belief “that our apprehension of the world, both past and present, arrives only through the lens of language’s precoded perceptions,” but that these were always subject to the instabilities and indeterminacies inherent in language. Spiegel explores the impact of poststructuralism on historians, and notes its waning influence in recent years, a trend she largely endorses. But she concludes her address with a powerful argument for preserving some core features of poststructuralism, especially those which derive from the psychological rupture she evoked in the beginning of her address. For, she observes, the contemporary world is itself marked by multiple ruptures, especially when we consider it in terms of the transnational experiences of migration, diasporas, uprooting, exile, expatriation, and the like. “Whither history,” she asks, in the face of these fragmented accounts of the displaced? Preserving the insights of poststructuralism into the slippages, gaps, and multiplicities inherent in language will help us, she concludes, “solicit those fragmented inner narratives to emerge from their silences.”

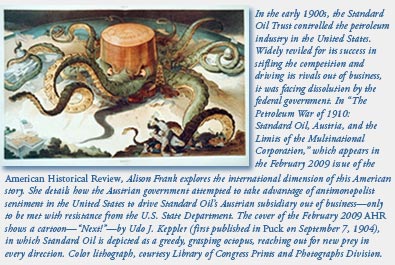

Alison Frank’s article, “The Petroleum War of 1910: Standard Oil, Austria, and the Limits of the Multinational Corporation,” offers a case study of the interaction of government and multinational business in the early years of the 20th century. She focuses on an episode that pitted Standard Oil, in league with the U.S. State Department, against Austria, which was seeking to drive Standard Oil’s Austrian subsidiary, Vacuum Oil, out of business. Standard Oil’s success in securing the State Department’s protection—despite the fact that at just this moment Standard Oil was facing antitrust action—illustrates the intimate connection between diplomacy and economic activity in the prewar era. It also reveals that even multinational corporations maintained national affiliations and could claim to represent national interests. As much as corporations insisted upon their autonomy and loudly resisted government intervention, when necessary they readily turned to the government for support and protection. Frank’s article illustrates the multiple connections between oil producers and refining industries in Austria, France, and the United States, and thus adds to the growing scholarship on transnational history. At the same time, however, it points out the limits of those transnational linkages, suggesting the enduring importance of “international,” as opposed to transnational, history.

The February issue also contains the first part of an AHR Forum on “The International 1968,” a forum planned to coincide with the 40th anniversary of that year of revolt, mass protests, and social upheaval, especially on the part of the young and students, across much of the world. The first article, “The Rise and Fall of an International Counterculture, 1960–1975,” by Jeremi Suri, presents both a context and an interpretation of that momentous year, emphasizing how the international counterculture challenged contemporary assumptions about the “good life” across diverse societies. Suri argues that Cold War policies, usually condemned for thwarting social change, actually encouraged and legitimized this counterculture. State leaders endorsed expanded educational opportunities and cultural innovations in order to more effectively compete against international adversaries. They made broad ideological claims they could not fulfill. In nearly every major society, young men and women asked why government policies did not produce the promised outcomes, why their country was falling short. Scholars frequently treat the social history of the counterculture as something separate from the political history of the Cold War, but the two were in fact deeply intertwined, Suri asserts. Cold War ideas, resources, and institutions made the counterculture. His article offers a transnational history of social and political change and suggests some legacies of the 1960s for the 21st century.

Timothy S. Brown’s “‘1968’ East and West: Divided Germany as a Case Study in Transnational History,” examines youth rebellion in the two Germanies, capitalist West and communist East. His article explores two sets of critical connections: those between the two Germanies, and those between these countries and the wider world, including the bloc systems of which they were members. Like Suri, Brown argues that “1968” cannot be understood in terms of the nation-state, not only because of the importance of transnational influences on local events but also because the contentious events of that year were linked to a globalizing imagined community that cut across national boundaries. By identifying transnational vectors of influence, analyzing their modes of transmission, and exploring how they meshed with local concerns, goals, traditions, and histories, this article offers a new perspective on the history of postwar Germany and the international 1968.

The last article in the first part of this forum is “Japan 1968: The Performance of Violence and the Theater of Protest,” by William Marotti. He begins by noting that the early 1960s saw mass protests and strikes against the renewal of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. While these failed in the securing the protestors’ goals, events such as the Vietnam War, Chinese nuclear tests, and conflict with North Korea pointed to 1970, when the treaty was scheduled for renewal, as a potentially explosive date. By 1967, however, public concern was waning and the opposition was in disarray. The outburst of large-scale protest in late 1967 and 1968 thus came as something of a surprise, inaugurating a period of renewed popular mobilization, nationwide university seizures, and threats to the government’s very existence. Marotti sees this period as the emergence of a new kind of politics of physical confrontation with the state. These confrontations attracted increasing public attention and ultimately created a space where new forms of activism could arise, spaces in which, somewhat paradoxically, nonviolent tactics could again become effective. Ordinary people, not only activists, increasingly found the will and means for political engagement. In October 1968, however, the cycle was reversed, with the state successfully pushing back against demonstrators, enabling the isolation and suppression of dissent.

The second part of this forum will appear in April’s issue, with articles on Latin America, feminism, Eastern Europe and Russia, and youth tourism.