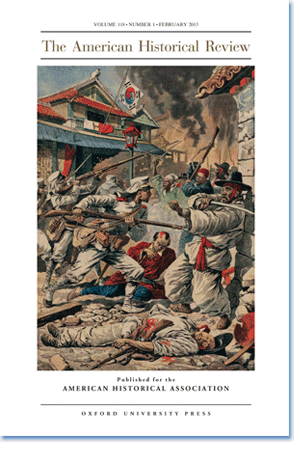

“Les troubles de Corée: La garde japonaise aux prises avec les émeutiers à Séoul,” Le Petit Journal illustré, August 4, 1907. Following Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese government imposed protectorate rule in Korea in 1905, the first step toward formal annexation in 1910. When the Korean emperor, Kojong, sent a secret delegation to the Hague Peace Conference in 1907 to protest this occupation of his country, he was forced by Japan to relinquish the throne. In the wake of his abdication, armed resistance by Koreans swept the country. La Petit Journal illustrates a battle scene in Seoul between Japanese troops and the Korean resisters. In the midst of this turmoil was the Ilchinhoe (Advance in Unity Society), a large local group whose members viewed Japan as a “civilizing empire” and were willing to sacrifice Korea’s sovereignty in the name of “representing the people.” In “Immoral Rights: Korean Populist Collaborators and the Japanese Colonization of Korea, 1904–1910,” Yumi Moon examines the vexed position of these populists, who were trapped between their original agenda and their commitment to support the Japanese Empire. Moon uses this case study to historicize the moral dimensions of local collaboration in colonial situations and defends the validity of using the concept of collaboration in historical analysis.

The February issue of the American Historical Review should be in members’ mailboxes and available online soon. It contains William Cronon’s presidential address, followed by an article on the question of collaboration in Japan-occupied Korea and an AHR Forum on “Transnational Lives in the Twentieth Century.” There are also three featured reviews, along with our usual extensive book review section. “In Back Issues” draws attention to articles and features in the AHR from 100, 75, and 50 years ago.

In “Storytelling,” outgoing AHA president William Cronon offers us an extended meditation on the writing and teaching of history in the face of contemporary challenges only partially described by the much-mooted “digital age.” For historians—and anyone interested in the value of thinking about the past—the obstacles are daunting indeed, hardly limited to the shortage of funding from our institutions, the short attention spans of our students, the lack of interest on the part of the public, or the distractions from a plethora of social media. The problem often lies, he asserts, with our own inability to speak to those outside our profession, to a larger public that both craves and needs what we know. Referring to Carl Becker’s oft-cited AHA presidential address of 1931, “Everyman His Own Historian,” he writes, “keeping the past alive for the wider public is the essential mission of our discipline, on which all our other activities ultimately depend.” Cronon’s answer to the question he poses, “what is the future of history?” brings him ultimately to the title of his address. It is in rediscovering the virtues of writing and teaching history as storytelling that we might recapture a wider audience for the extraordinary storehouse of knowledge and expertise we have accumulated. To illustrate his case, he ends with an evocation of his undergraduate teacher Richard Ringler, an English professor specializing in Anglo-Saxon literature, who combined deep erudition with a commitment to teaching, and especially undergraduate teaching, in ways that sent at least one student, William Cronon, into a lifetime of storytelling as history.

In recent decades, many scholars have cast doubt on the analytical usefulness of the concept of collaboration, and have tended to avoid interrogating the moral dimensions of local collaboration in colonial situations. In “Immoral Rights: Korean Populist Collaborators and the Japanese Colonization of Korea, 1904–1910,” Yumi Moon pursues this critique by historicizing the moral crises of local collaborators in the changing normative and material context of Korea under the Japanese colonial conquest. Her focus is on the Ilchinhoe, an organization of Korean collaborators who were active during Japanese protectorate rule in Korea (1905–1910). The Ilchinhoe regarded Japan as a “civilizing empire,” and thus were willing to sacrifice the sovereignty of the Korean monarchy on the premise that the empire would guarantee the people’s rights and welfare. Most Koreans, however, felt very differently, viewing the movement’s embrace of Japanese rule as fostering only “immoral rights.” This moment of conflict thus signifies a global ideological juncture at which the morality of “civilizing empires” was decisively rejected by colonial “subjects” who refused to accept notions of rights and freedom that undermined national legitimacy and collective rights.

TheAHR Forum, “Transnational Lives in the Twentieth Century,” offers three sets of portraits of individuals whose travels and experiences bring interesting and important features of their worlds to light, features that might very well have remained hidden or obscured without the individual trajectories reconstructed by these historians. These are not biographies, and in some cases the focus strays from these subjects to the social and cultural contexts they encountered. They are, rather, “lives”—slices of life experiences that serve as tracers for the many, and often unexpected, connections and cross-currents that, in retrospect, fashioned more of 20th-century history than we have realized.

In “Revisiting the Transatlantic 1920s: Vincent Sheean vs. Malcolm Cowley,” Nancy Cott compares the content and the reception of two autobiographical accounts of Americans abroad in the 1920s, with an eye toward their influence on the later historical understanding of their generation. Each intended to convey the zeitgeist of those coming of age after World War I. Each, however, offered a very different view of this cohort of writers and intellectuals. Malcolm Cowley’s account told of literary “exiles” seeking solace in Europe’s cultural capitals through the pursuit of art for art’s sake, but ultimately doomed by their own rootlessness to a failed quest, and destined to rediscover purpose only on native soil. Vincent Sheean’s account, which became a bestseller, evoked an ongoing global pilgrimage of youth in search of self-definition. Cott’s article weighs the consequences of Cowley’s outsized influence and suggests that taking Sheean’s book as a guide instead of Cowley’s would lead toward revising views of Americans as internationalists in that era.

From these literary figures, Stephen Tuck takes us to a somewhat later time, a very different context, and a much better-known individual. In “Malcolm X’s Visit to Oxford University: U.S. Civil Rights, Black Britain, and the Special Relationship on Race,” he goes beyond that visit on December 3, 1964, when Malcolm X delivered what many historians consider to be his finest speech. His brief stay allowed him to make connections with black Britons and radical students from the Caribbean, Africa, and Pakistan; his subsequent European travels gave him a new perspective on the global struggle for racial equality. In turn, his visit hastened the success of local Oxford student protesters, and radicalized a new generation of black British activists. More broadly, Tuck argues, Malcolm X’s journey points to widespread connections between British and U.S.-based activists at the height of anti-racist protests in both countries, connections that were strengthened by the growing presumption of a shared trajectory in so-called race relations. A closer look at this rather different special relationship reveals the ways in which British and American activists sought to use transnational links for their own domestic purposes, even as these connections changed them, often in unexpected ways.

In “Phantoms of the Archive: Kwame Nkrumah, a Nazi Pilot Named Hanna, and the Contingencies of Postcolonial History-Writing,” Jean Allman reconstructs the encounter between Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, and a Nazi test pilot, Hanna Reitsch, and the establishment of a flight school in Ghana in the early 1960s. The story is a strange one, but she uses it in order to expose the dispersed, fragmented, and accidental nature of the postcolonial archive. Other scholars have debated the nature of the “archive,” but their focus has largely been on colonial archives as constituted by Europeans. Do postcolonial archives, Allman asks, simply reproduce the potentialities and limitations of these, or are they of a very different order, presenting both new possibilities and challenges for the writing of African history? By bringing this encounter of these two figures to light, she argues that evidentiary fragments—either buried in mislabeled files in Ghana’s national repository or dispersed in a vast transnational “shadow archive”—not only trouble the notion of a “national archive,” but point toward new history-writing possibilities, which are far less anchored in, far less dependent upon, and thus less determined by the archiving apparatus of a postcolonial nation-state.

In a comment on the forum, “The Futures of Transnational History,” Matthew Pratt Guterl offers both an appreciative reading of these three pieces and a challenging critique. He notes that the focus on lives, and especially on snippets of biographies as telling indicators of global stories, is an important part of the transnational approach to history, which can serve to humanize processes that otherwise might seem too abstract or difficult to trace. Each of these essays, indeed, tells us something new and important about its particular subject, about the larger context, and about the way we connect biographical, national, and international plotlines. But Guterl notes as well that the authors tend to affirm “nation time,” the already agreed-upon “eras” and “periods” that structure conventional history. The challenge of the future for transnational history, he suggests, is to break free of this commitment to national chronologies—to rebuild our larger, still nation-based assumptions into new synthetic shapes and forms.

April’s issue will include two articles relating to animals and humans in history: one on beasts of burden in the Ottoman economy, the other on whales in the North Pacific; as well as pieces on encounters between Jews and Christians in the early modern period, Muslim travelers to the West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and erotic photography in postwar Germany.