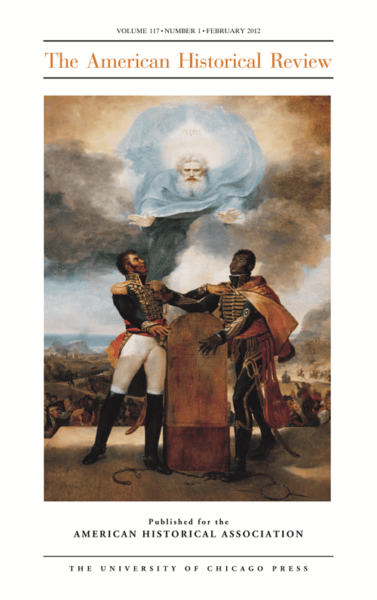

Le serment des ancêtres (The Oath of the Ancestors, 1822), by the prominent French artist Guillaume Guillon Lethière, a free man of color born in Guadeloupe who lived and worked in Paris. The painting, which Lethière secretly sent to the Haitian government as a gift, represents the October 1802 union of Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Alexandre Pétion, representing the alliance between black and mulatto forces that paved the road for the French defeat and Haitian independence on January 1, 1804. At the feet of the two men are the broken chains of slavery and a stone tablet, on which are engraved references to the nation, liberty, and the constitution. In “Haiti, Free Soil, and Antislavery in the Revolutionary Atlantic,” Ada Ferrer argues that early Haitian leaders affirmed, and projected internationally, what they conceived as an essential link between antislavery, sovereignty, and the law. Lethière’sLe serment des ancêtres provides a stunning visual representation of that link. The painting, which was on permanent display in the Presidential Palace in Port-au-Prince, was severely damaged in the January 12, 2010, earthquake and is currently undergoing restoration in Paris.

The February 2012 issue of the American Historical Review will soon appear both in members’ mailboxes and online. It opens with the 2012 AHA Presidential Address, followed by an article on antislavery in the Atlantic world and an AHR Forum, “Liberal Empire and International Law.” There are also three featured reviews, followed by our usual extensive book review section. “In Back Issues” draws attention to articles and features in the AHR from 100, 75, and 50 years ago.

In his presidential address, “The Republic of Letters in the American Colonies: Francis Daniel Pastorius Makes a Notebook,” Anthony Grafton introduces us to a man of ceaseless curiosity and intellectual appetite. Pastorius was born in Germany but migrated to America, settling in Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1683, where he lived for the rest of his life. Although he came to the New World in search of a simpler existence, his life was happily burdened by intellectual and scholarly endeavors that took him deep into the culture of antiquarian erudition that still flourished at the end of the 17th century. Posterity remembers him for his commonplace book Bee-Hive, which, as Grafton points out, was only one of the many “magnificent information-retrieval machines” he produced. In looking at Pastorius’s activities, Grafton shows us how 17th-century scholars read, and especially how they valued books. But despite his antiquarian bent and deep commitment to traditional scholarship, Pastorius was, as Grafton argues, an exemplar of an overlooked source of the Enlightenment, with “roots deeply set in an older world of European learning and Christian belief.”

The Haitian Revolution has, in recent years, moved from being a peripheral event to a central concern for historians of the 18th and 19th centuries. In “Haiti, Free Soil, and Antislavery in the Revolutionary Atlantic,” Ada Ferrer looks at the impact of that emancipatory movement on neighboring societies. Focusing on a little-known case from 1817, she explores the ways in which notions of freedom among slaves were shaped not only by the example of the Haitian Revolution but also by the actions of the Haitian state after independence. She demonstrates that the Haitian government was engaged in an important way that has gone largely unexplored, and that the early Haitian republic, drawing on both Old Regime attempts to restrict slavery geographically (such as “free soil” policy) and revolutionary notions of total emancipation, did in fact project its antislavery influence abroad, thus participating in the international debates on both slavery and freedom.

The AHR Forum, “Liberal Empire and International Law,” confronts the relationship between law and empire from three perspectives. In “The Liberal Traditions in the Americas: Rights, Sovereignty, and the Origins of Liberal Multilateralism,” Greg Grandin suggests that one aspect of the much-celebrated “exceptionalism” of the United States is its unique relationship to Latin America. In contrast to world powers such as France, Holland, and Great Britain, which viewed the peoples they ruled over as culturally, racially, and religiously distinct, the settlers who colonized North America viewed Iberian America not as an “other” but as a competitor in a struggle to define a set of nominally shared—and also contested—values and political concepts: Christianity, republicanism, liberalism, democracy, sovereignty, rights, and, above all, the very idea of “America.” After the republican revolutions of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the relationship between the U.S. and the new nations of Spanish America was characterized by both contention and intimacy—a rivalry over a shared republican legacy. Grandin’s essay compares and contrasts the two sides of this rivalry, focusing especially on notions of rights and sovereignty.

In “Empire and Legal Universalisms in the Eighteenth Century,”Jennifer Pitts notes that throughout the modern period, the law of nations has been both distinctively European and universal in its aspirations. Its possible or practical universality, however, has been a vexed issue, with significant moral and political implications. Looking back to the 18th century, she brings to light forgotten critical approaches to the question of the scope of the European law of nations and the nature of legal relations between European and non-European states and peoples. These approaches regarded a global legal order, or a network of orders, as a constraint on the exercise and abuse of European states’ power.

In “Liberalism and Empire in Nineteenth-Century International Law,” Andrew Fitzmaurice notes that international law was employed primarily to justify the domination of European states over the rest of the world. His article focuses on the debates and divisions among liberals in the late 1800s over the colonization of the Congo. As some liberal international lawyers developed a new legal vocabulary to justify the expansion of empire, others mounted an opposition that only strengthened as the race for empire gathered pace. This opposition was based not on humanitarian sentiment but rather on self-interested concerns about the security of liberal reforms and revolutionary changes within Europe. Fitzmaurice concludes by reminding us that while the liberal tradition has often justified expansionism, it also contains the resources to oppose it.

In his Forum comment, “Empire and Its Anxieties,” Anthony Pagden plays on the distinction, brought out in Pitts’s and Fitzmaurice’s articles, between European empires before the 19th century and those of the later period. The key to this difference, he argues, is to be found in the liberal revolutions of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, which joined rights with citizenship in the nation-state, for it was sovereignty that conferred the legal status by which non-European peoples were found lacking and thereby were subject to conquest. As products of those revolutions, the new nations of the Americas had even less claim to empire than their European counterparts. Nevertheless, they still were confronted with peoples and lands that had to be incorporated into the nation-state, although not through the kind of imperial conquest that would have entailed shared sovereignty. Instead, the United States, at least, has either relied upon de facto justifications for intervention or foreign occupation, or “fallen back on robustly Roman declarations of political and cultural superiority in defense of supposedly universal political values.”

The April 2012 issue of the AHR will include articles on the cultural history of scholastic disputation, the colonization of North America, the “Mexicanization” of American Politics in the late 19th century, the Mediterranean slave trade in the 19th century, and Parisian modernism and African sculpture in the 20th century.