Photo: Rachel Davila Ramirez

New York never loses its capacity to surprise. Of course, the same is true of other cities, but in New York the consequences of population density and diversity oblige the close mingling of races and classes that often astonishes visitors. “How curious you are to me!” exclaims Walt Whitman about his fellow passengers in Crossing Brooklyn Ferry. Surprise is the operating premise that has given the Law & Order franchise its purchase on television for more than a quarter century. Every weeknight the plot twists and turns on some feature of neighborhood, race, religion, class, or real estate. The element of surprise gives New York theater, social protest, real estate, and city politics their vitality.

Visitors to New York who have not been here since the 2009 AHA meeting will find the skyline changed. One World Trade Center has now reached its full height of 1,776 feet, shifting the balance of the skyline toward downtown. Daniel Libeskind’s original design was radically altered, however, to address the security apprehensions of federal and local authorities and the financial concerns of real estate interests. Next door, the 9/11 Memorial Museum is now open to the public. Most critics agree that the museum has done an admirable job of commemorating that traumatic moment.

Elsewhere, Lower Manhattan is undergoing a revival. The resurgence of Wall Street—physically and financially—proceeds apace, well ahead of other sectors in the city, and the result has been a dramatic expansion of Lower Manhattan’s residential development. The once-mighty fortresses of American finance, built to withstand anarchist attacks, have been gutted and refitted with rooftop swimming pools, fitness rooms, and spas for returning derivatives traders and hedge fund managers. Acronymic neighborhoods that abound in Downtown and nearby Brooklyn (e.g., NOLITA = North of Little Italy; DUMBO = Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass) offer new dining and entertainment opportunities.

Gigi Altarejos, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Central Park, Bethesda Terrace Arcade

Visitors and urban planners from across the globe have found themselves drawn to another of Lower Manhattan’s distinctive attractions, the High Line, inspired by the Promenade Plantée in Paris. At once a garden and a traffic-free urban oasis, this elevated promenade evolved out of a dilapidated West Side rail line linking warehouses from the Meatpacking District to Penn Station. Now open from Gansevoort Street to West 30th Street, the High Line will eventually extend to the rail yards just west of Penn Station, where it will connect with the extension of the Number 7 subway line, scheduled to open in 2015.

Nature has conspired to offer another transportation surprise for visitors: in 2012 Hurricane Sandy devastated subway tunnels, homes, and businesses in low-lying areas of Lower Manhattan, Staten Island, Brooklyn, and Queens. Some neighborhoods and subway lines are still under repair. The city and state have undertaken a restoration effort estimated to cost over $5 billion on the subway lines affected by Sandy, with additional efforts to insure that the tunnels and stations will be resistant to storm surges in the future. The metropolitan area is currently rethinking its relationship to New York harbor, the rivers, and surrounding wetlands in order to provide increased security against climate-induced storm surges in the future. Under the present mayor and his predecessor, the city has begun to think about the causes as well as the consequences of climate change: Gotham has been at the forefront of American cities in supporting energy sustainability and announcing plans to use wind and solar power for its buildings and transportation in the future. Brooklyn’s tallest building, 388 Bridge Street, is now partially powered by wind turbines. The city is constructing a 250-acre solar energy plant on the enormous Fresh Kills Landfill site on Staten Island.

The 2010 Census data reveal a city that has undergone significant demographic changes since the turn of the 21st century. New York continues to be very cosmopolitan: Queens was listed in the 2010 Census as the most ethnically diverse of American counties. Yet New York’s demographic mix is changing. Although African migration to New York has surged, the city has suffered a loss in the proportion of African Americans living in the metropolis; the African American population of New York in 2010 was 25.5 percent of the population, down from 26.6 percent in 2000. The Latino population has grown to 28.6 percent of the population, up from 27.0 percent in 2000. While the overall number of Hispanics in New York has increased, the Puerto Rican population has declined somewhat. Offsetting this decline has been an increase in migrants from Mexico and Central and South America. New York’s Dominican population has remained stable, and Dominicans are now the largest Hispanic group in the five boroughs. New York has seen a dramatic influx of new immigrants from China, India, Pakistan, and other nations in Asia, who now total 11.8 percent of the population. Overall, 37 percent of New Yorkers were listed in the Census as foreign-born—the highest percentage since 1910.

The new diversity is changing whole neighborhoods of New York; for example, Chinatown has expanded to the point where it has nearly engulfed Little Italy. If the outer boroughs of New York are becoming more diverse, Manhattan and some parts of Brooklyn are becoming more homogeneous. From the Battery in the south to Inwood in the north, Manhattan Island has become richer, whiter, and older in the past decade: non-Hispanic whites counted for 57.5 percent of the population in 2010, up from 45.8 percent in 2000. Rents for apartments are often beyond the aspirations of even upper-middle-class professionals, and this is changing the character of some of Manhattan’s iconic neighborhoods: Harlem, Chelsea, and the East Village, to name a few. The same trend is apparent in parts of Brooklyn, notably in Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope, but also in adjacent areas that are pricing themselves out of the reach of young families.

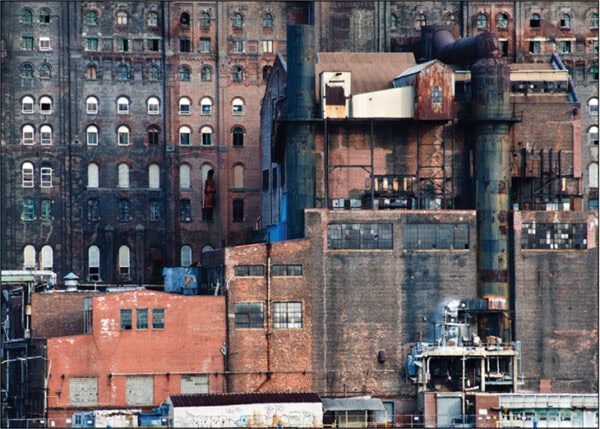

Claude Robillard, CC BY-NC 2.0

Domino sugar factory in Brooklyn, New York

The growing economic inequality in New York City has manifested itself in many ways that are worrisome to residents and visitors alike. New stadiums have appeared: Barclays Center in Brooklyn, Citifield in Queens, and Yankee Stadium in the Bronx. All offer luxury boxes and every culinary amenity, yet the ticket prices in the cheap seats are too high for blue-collar New Yorkers. Broadway musicals providing family entertainment often cost more than $500 for four seats—more than double the price of London’s West End theaters. The Metropolitan Opera seems to have survived its latest labor dispute, but its feisty sister company, the New York City Opera, is now in bankruptcy. The city’s growing inequality is closing off the opportunities for the mingling of classes and races that are commonplace on the subway and that Whitman celebrated on the Brooklyn ferry. The social and cultural impact on New York is painfully manifested in the public schools. Increasing inequality figured prominently as an issue in the recent election of Mayor Bill de Blasio.

The frustration with growing inequality fueled the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement, which was inspired in part by the tactics of the Arab Spring. OWS helped give rise to other Occupy movements in cities throughout the United States. The Occupy movement surprised many New Yorkers because it did not seem to have an explicitly political agenda. Unlike the anti-Vietnam and hard-hat protests in the 1960s, OWS seemed to enjoy some support among all classes of New Yorkers, including a few “one percent” employees of hedge funds and investment banks.

Has Manhattan regained its style and its safety only to lose its soul? Many of those who live here keep the faith in New York’s uncanny ability to surprise. Who would have predicted that New York would rebound after the draft riots of the 1860s or the urban decay of the 1970s? Today’s New Yorkers are pioneering new approaches to an affordable, livable, sustainable city. Brooklynites are working to make the Gowanus Canal, a toxic Superfund site, into an alluring urban waterscape. Bicyclists are volunteering to help expand the West Side bike trail that extends from Battery Park to the George Washington Bridge. Music lovers enjoy free concerts of classical music, opera, jazz, hip hop, R&B, punk and salsa throughout the year in parks and public buildings.

We may yet see the resurgence of a new “Mongrel Manhattan”: innovative approaches to the wondrous amalgam of high culture and low for which New York is famous. New York may be the oldest major US city (1624), but Gotham is remaking itself in new ways that look to the future. Taking inspiration from urban activist Jane Jacobs, urban planners and many city dwellers are promoting livability, affordability, diversity, revived infrastructure, green energy, and a revitalized public transportation system.

is cochair of the 2015 AHA Local Arrangements Committee. He teaches at the Graduate Center and Lehman College, City University of New York. He is a historian of the early American republic and is at work on a new book, Early American Democracy: America’s Other Peculiar Institution.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.