Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a two-part column. The first column is available here.

Whenever I find myself irritated by constant car noise and the endless concrete of urban space, getting my hands in the dirt tethers me to a type of landscape that defined my upbringing.

Moving from her rural home to a city for graduate school sent Cecilia Slane looking for green places. Cecilia Slane

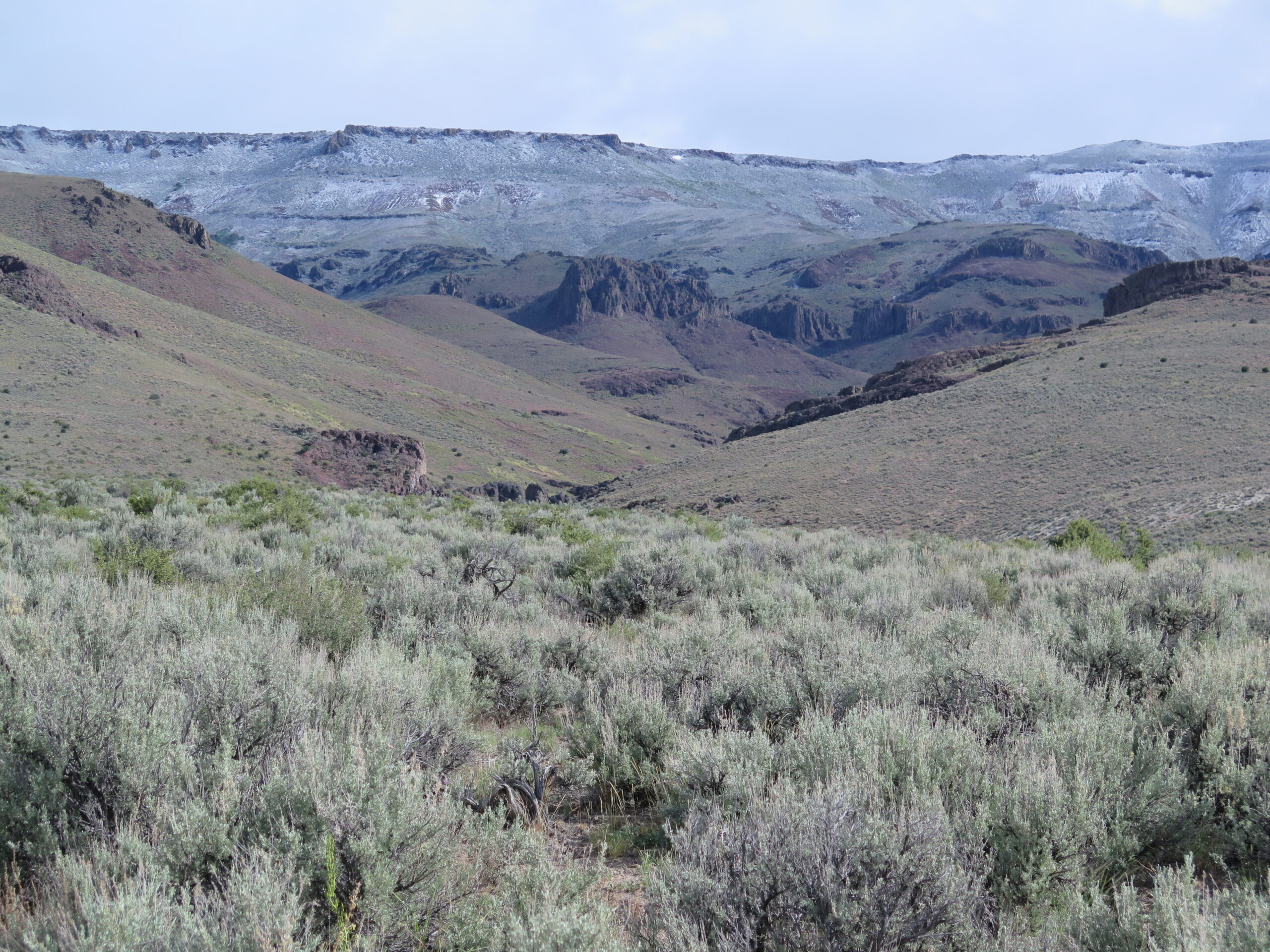

I grew up in rural southern Illinois. My family’s house sits a few miles from town, surrounded by fields of corn and soybeans on rotation. Hardly any other crop is grown, except what people manage in their own yards. Scattered throughout those fields are pumpjacks extracting Illinois oil and emanating a slow, steady creaking noise at all hours of the day. White-tailed deer, coyotes, bobcats, rabbits, and free-ranging dogs and cats share these fields with the few farmers and oil workers who manage them.

Like in many other regions of the rural Midwest, life revolves around the growing season. Though my family left the farming business in the mid-20th century, agriculture remains central to local culture, politics, and social routines. For example, during middle and high school many of my friends made extra summer cash by detasseling corn in those fields, often waking up before dawn to do so. But I didn’t realize how important this rural environment was to me until I moved to a metropolitan area for graduate school in 2021.

That fall, feeling smothered by the ratio of concrete to grass at my apartment complex in Norman, Oklahoma, and desperate to meet new people, I searched on Facebook for “community gardens near me.” I was involved with environmental and sustainability projects while earning my bachelor’s degree at DePauw University, so I was eager to get outside and meet other folks with similar interests in this new city. Facebook led me to a garden at Colonial Commons Park, where I met a half dozen people tending to a few raised beds and a trellis.

Feeling smothered by the ratio of concrete to grass and desperate to meet new people, I searched on Facebook for “community gardens near me.”

I visited the garden sporadically over the next couple years. Though I struggled to attend early Saturday morning workdays, I met many neighbors who themselves were transplants to Norman at the garden’s big harvests and events. Yet around the time I began preparing for general exams, I also increased my commitment to the garden. I began attending workdays more frequently, which quickly became an anchor in my weekly routine. For two hours every Saturday, I could get my mind off the giant to-read pile haunting my waking hours by focusing on mundane garden work: weeding.

Weeding is a constant, necessary battle in a garden. It is physically taxing, especially because our garden prioritizes mechanical solutions over petrochemical ones. While pulling at the roots of unwanted plants, we gardeners chat about our mutual love of fresh produce and our mutual hatred of Bermuda grass. We discuss local news, recent art projects, and our plans for the day.

Some days, I focused on the weeds alone, dealing with exam stress by pulling deep at the roots or gently tearing them apart from the base of desirable, fruiting plants. On better days, the mundane, repetitive task—dig, grab, pull, dig, grab, pull—gave me space to think through the texts I had read that week. The repetitive motions gave my hands something to do while I cycled through my mental filing cabinet of recent historical arguments in my exam fields: the history of science, technology, and empire; energy and environment; extraction and envirotech; and critical methodologies. After an hour, I had dirty hands, burgeoning calluses, and a page of digital notes on my phone explaining new connections I had made between concepts. Extraction, for example, was no longer just an abstract description of global mining and distribution processes. The physicality of extraction—the displacement of materials—wasn’t in a faraway mine or book. It was in the weeds I had torn from the ground and held in my hands.

Cecilia Slane

Having passed my exams, I’ve spent this summer refining my dissertation prospectus and thinking about where the next few years will take me. After writing a master’s thesis on the oil industry and environmental knowledge, my research interests have turned to a fuel that has garnered less attention: peat. A partially decayed vegetative material that gathers in wetland environments, peat is often considered in terms of energy or agriculture, as much of the existing literature discusses how peatlands were dug up and dried for fuel or drained for growing crops. Draining wetlands can result in nutrient-rich crop lands, and the removal of water-logged conditions is necessary for growing crops like corn and soybeans. This process (alongside the removal of forests and prairies) was undertaken throughout various parts of the Midwest through the installation of drainage tile and irrigation systems. Subsurface pipes undergird much of the heartland, including the fields across from my childhood home, to manage the relationship between soil and water. Peat has even made its way into my new home garden in Oklahoma. Called “peat moss” on my bag of potting soil, sphagnum moss (a defining plant of peatlands) is often mixed with soil on account of its water-absorbing properties.

Focusing on the materiality of peatlands has allowed me to think through the practices of science, technology, energy, and empire within wetlands. Peatlands have been drained and altered for commercial agriculture, dug up for fuel, filled in for development, and, rarely, set aside for preservation. When browsing the New York Times archives for the word “peat” around the turn of the 20th century, I found most articles discussed peat as a replacement for other fuels during shortages in North American and European countries. While peatlands have more recently been valued for the energy they can provide, they have also long been considered undesirable environments, home to malaria-carrying mosquitos, difficult terrain, and, sometimes, impoverished people. A short article from 1933 recounts how a Chicago peatbog was used as a “city dumping ground” until nearby factories closed down. The newly unemployed workers built homes near the bog, using materials from the dumping ground, and extracted peat for fuel. This peatbog went from a place for waste to a refuge. And as I write paragraphs that may one day may find themselves in a finished dissertation, I find my editing akin to weeding and other forms of environmental management: identifying and isolating the desirable parts from the undesirable parts to achieve a specific end.

The physicality of gardening and the endless metaphors of ecology have provided me with different ways to think about historical relationships between humans and nonhumans

Gardening has become part of my methodological toolkit for doing history. Weeding in particular has been an excellent activity for stress relief, helping me to think through problems and providing a reprieve from and connection to the city. The physicality of gardening and the endless metaphors of ecology have provided me with different ways to think about historical relationships between humans and nonhumans, especially in terms of energy and agricultural production. Incorporating plant cultivation into my daily and weekly routines has become increasingly important to my research about the history of fossil fuels and the life sciences, but also to my identity, as one of those rural people seeking “opportunity” in the city.

On any given Saturday, you can find me weeding or writing, trying to solve the problems of the week by pulling at the root.

Cecilia Slane is a PhD candidate in the history of science, technology, and medicine at the University of Oklahoma, where she studies fossil fuels in the history of science, technology, and settler colonialism.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.