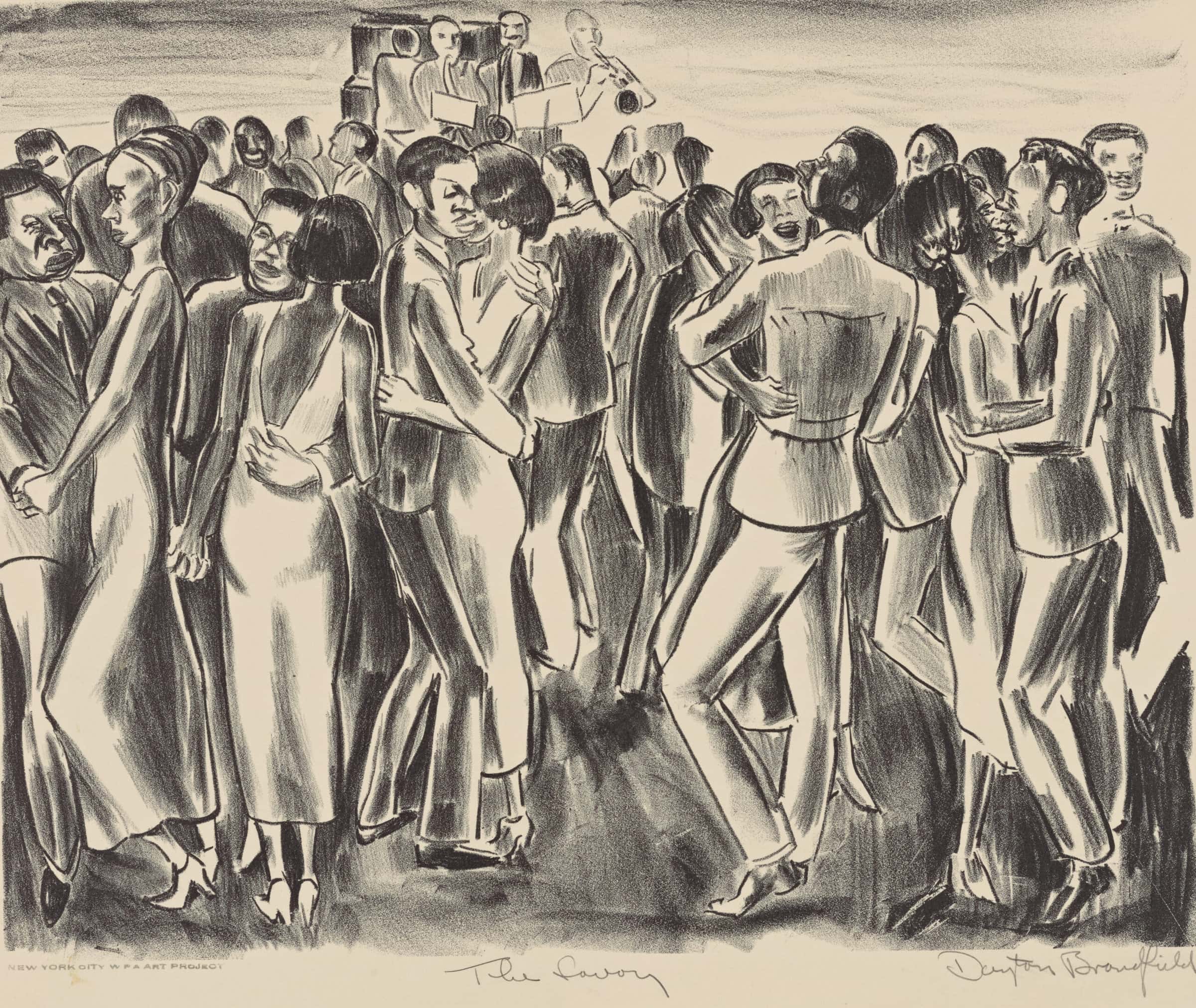

Book cover of Shane White’s Prince of Darkness. Jeremiah Hamilton was the first black millionaire to amass his riches on Wall Street. No photographs or sketches of Hamilton have survived into the present day. www.jeremiahhamilton.org

On February 27, 1828, 20-year-old Jeremiah Hamilton arrived secretly at Port-au-Prince Harbor, Haiti, aboard the brig Ann Eliza Jane. For the next few days, the young man slipped in and out of the city to distribute counterfeit Haitian coins supplied by prominent American businessmen. When authorities discovered the scam, a $300 bounty and a death sentence were put on his head. After hiding out for 12 days, the counterfeiter managed to escape on a ship bound for New York City. Hamilton was subsequently vilified in African American newspapers as a discredit to his race. Forty-seven years later, this same “base villain”—as a letter printed in Freedom’s Journal described him—would die the richest black man in the United States.

Hamilton’s impressive and unlikely rise to infamy captured the attention of Australian Shane White, a professor of US history at the University of Sydney. The scholar’s latest book, Prince of Darkness: The Untold Story of Jeremiah G. Hamilton, Wall Street’s First Black Millionaire (St. Martin’s Press, 2015), is a biography that does something rare in the profession nowadays: it starts from scratch.

You’ve probably never heard of Hamilton—the first, and only, African American broker to join mid-19th-century New York’s millionaire’s club. Rising from cryptic origins, Hamilton bullied his way onto Wall Street, becoming no less than an antebellum “master of the universe.” He amassed a fortune of $2 million, the equivalent of a quarter of a billion dollars in today’s money. His reputation earned him derogatory nicknames in the newspapers; one, “Prince of Darkness,” referred not only to his skin color, but also to his questionable methods of moneymaking.

Readers aren’t necessarily supposed to like Hamilton, though one can’t help but admire his sheer gall. The broker intentionally kindled an aura of mystery around his past, and White is unsure if he was born to free parents in Virginia, as contemporary accounts suggest, or the West Indies, as is printed on his death certificate. Hamilton cut his teeth in the business world by orchestrating the Haitian counterfeiting ruse and, by the 1830s, was well on the path to building a personal empire. In the midst of a segregated, racially tense New York, Hamilton freely worked out of an office on Wall Street, participated in the city’s real estate boom, and invested in land and property around the Hudson River. In the 1850s, Hamilton sued tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Accessory Transit Company, which earned him the notoriety of being referred to as the only “man who ever fought the Commodore” in Vanderbilt’s obituary.

You’ve probably never heard of Jeremiah Hamilton before—the first, and only, African American broker to join mid-19th-century New York’s millionaire’s club.

As the sole black participant in an otherwise exclusively white domain, Hamilton endured what White calls “an impossibly schizophrenic way of living.” The highlights of his life border on the anachronistic: he purchased a rural New Jersey mansion, married and had children with a white woman, and owned stock in railways that denied access to members of his race. One of Hamilton’s contemporaries observed that he brazenly “assumed the privileges of a white man,” but he and others were unable to check his ambitions. He ignored, denounced, or outsmarted racial attacks, even thwarting a lynch mob during the Draft Riots of July 1863.

White says he is at the “ground zero” of all knowledge about Hamilton. In fact, a thread of disbelief runs throughout White’s language in Prince of Darkness, as if he feels someone else should have written this book first. White first casually noticed Hamilton’s name in a newspaper story and pursued leads from there. The bulk of his research is founded on two sources: New York City newspapers and court archives. While no photographs or sketches of Hamilton have survived into the present day, in life the millionaire was endlessly maligned and gossiped about in print. He was also an aggressive and prolific litigant, filing countless lawsuits to satisfy his whims. When he died in 1875, numerous obituaries across the country commented on his fortune and life’s work.

This does not mean that researching Hamilton was easy. Each scrap of evidence was hard won, and the historian estimates that he has traveled over a million miles by air between his office in Australia and New York City. White points out that most biographies on bookshelves today have had the advantage of earlier works on which to build. In contrast, Prince of Darkness comprises 13 chapters of original historical scholarship. White was able to unearth only four fleeting mentions of Hamilton’s name in secondary sources from the 20th century.

This does not mean that researching Hamilton was easy. Each scrap of evidence was hard won, and the historian estimates that he has traveled over a million miles by air between his office in Australia and New York City. White points out that most biographies on bookshelves today have had the advantage of earlier works on which to build. In contrast, Prince of Darkness comprises 13 chapters of original historical scholarship. White was able to unearth only four fleeting mentions of Hamilton’s name in secondary sources from the 20th century.

During his career, White has earned his fair share of raised eyebrows for being a scholar of African American and New York history with an Australian accent. However, he enjoys using his position as an outsider to his advantage. In a 2011 piece for the Chronicle of Higher Education called “An Aussie Takes On African-American History,” White wrote that “the experience of living in another society and working in another academic culture makes the historian more aware that what happened in America was not inevitable, and that there are many ways to interpret its history.”

Why have historians overlooked, or perhaps even ignored, the story of Wall Street’s first black millionaire? Perhaps, as White’s book shows, it is because he is utterly impossible to categorize. African American contemporaries were scandalized by Hamilton’s relentless financial scheming, and in turn, the broker made a point of ignoring New York’s black community entirely. Famed black physician James McCune Smith wrote, “Compare Sam Ward”—a respected antislavery activist—“with the only black millionaire in New York, I mean Jerry Hamilton; and it is plain that manhood is a ‘nobler idea’ than money.” Hamilton was at once an integral part of mid-19th-century African American identity and a stranger to it.

Publicity for Prince of Darkness has been somewhat limited due to the fact that White lives in Australia, and only a few American academics have been able to hear him speak on the topic. The historian also knows that there will never be a statue or other similar remembrance of the broker. Hamilton’s contemporaries—almost all of them his enemies—cared more about him than anyone does now. But in publishing his biography, White has created a fitting tribute to a man who had all but been forgotten.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.