Walt Whitman is New York’s patron saint of serendipity largely because of his capacity for embracing others empathically. As a result, the city never ceased to yield up surprises and discoveries that thrilled and enchanted him. Whitman changed the tradition of walking New York City forever when he made Gotham and its denizens his own. Whitman loved the city—its crowds, its multiculturalism, its physical landscape. And he embraced it all with a kind of cosmic empathy that acknowledged both immanence and transcendence. When you walk the streets of New York you will be walking in the footsteps of Walt Whitman. If there were still omnibuses roaring around Dead Man’s Curve on the southwest corner of Union Square, you might have seen Walt hanging onto the back of one reciting his epic poem “Song of Myself” to the crowds.

But one place you should go to truly understand what New York meant to Whitman is the Fulton Ferry Landing under the Brooklyn Bridge. There, carved into the metallic railing that surrounds the pier, are the words of the poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.”

It avails not, neither time or place—distance avails not:

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence;

I project myself—also I return—I am with you, know how it is.

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt;

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd.

Browning Photograph Collection, PR 009, New-York Historical Society, 83996d.

57th Street, looking east from Sixth Avenue, gelatin silver photograph, ca. 1920s-1930s.

During the annual meeting you will have a chance to experience and practice one of the great delights of being in New York City—serendipity. But what does that mean, exactly? “Serendipity”—the word—was actually invented by Sir Horace Walpole in a letter dated January 28, 1754. He wrote, “This discovery, indeed, is almost of that kind which I call Serendipity, a very expressive word, which, as I have nothing better to tell you, I shall endeavour to explain to you: you will understand it better by the derivation than by the definition. I once read a silly fairy tale, called ‘The Three Princes of Serendip’; as their Highnesses traveled, they were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of.”

Because of its size, density, and the fact that it is the most multicultural city in the world (in one Queens high school over 125 languages are spoken), the streets and neighborhoods of Gotham will provide you with an abundance of chances to make such discoveries.

But just as the King of Serendip hired a tutor to teach his princely sons how to cultivate this skill, we can learn from the long tradition of past “walkers of the city” who honed their proficiency in serendipity on the streets of Manhattan. Probably the first thing you need to know is how to look at the city streets. For this, let’s turn to one of the finest chroniclers of city life, A. J. Liebling: “The finest thing about New York City, I think, is that it is like one of those complicated Renaissance clocks where on one level an allegorical marionette pops out to mark the day of the week, on another a skeleton death bangs the quarter hour with his scythe, and on a third the Twelve Apostles do a cakewalk. The variety of the sideshow distracts one’s attention from the advance of the hour hand.” New York is a city of microcosms that is best approached by invoking the old Zen Buddhist aphorism “Everything changes, everything is connected, pay attention.”

Because New York is in constant flux, you have to add a level of time to your understanding of how to really see New York. As the novelist Colson Whitehead has written, “No matter how long you have been here, you are a New Yorker the first time you say, ‘That used to be Munsey’s’ or ‘That used to be the Tic Toc Lounge.’ That before the Internet cafe plugged itself in, you got your shoes resoled in the mom-and-pop operation that used to be there. You are a New Yorker when what was there before is more real and solid than what is here now.”

New Yorkers fell in love with walking streets because they were fascinated by theflaneurs of Paris and London in the 1820s and 1830s—Charles Dickens chief among them. Dickens was so admired that his visit to the city in 1842 was celebrated by a ball attended by 3,000 people and described as “the greatest affair of modern times.” Dickens marveled at the bustle of Broadway (though he abhorred the pigs that ran wild across his path) but found the Five Points slum “all that is loathsome, drooping and decayed.”

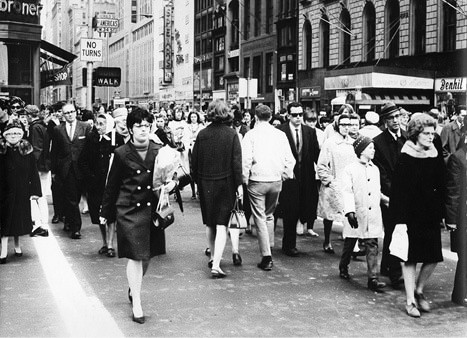

Frederick Kelly Photograph Collection, PR 246, New-York Historical Society, 87712d.

Frederick Kelly, Herald Square, 34th Street, New York City, gelatin silver photograph, ca. 1959-1976.

Native authors also were obsessed with observing and describing the extremes of street life in the city’s neighborhoods. Ned Buntline and George Foster were two of the first professional flaneurs who both exposed and weirdly celebrated this polarized city. Their kind of walking the streets led to elaborate descriptions of the Bowery with its “deep, dark, sullen ocean of poverty, crime and despair” and the gaudy, meretricious lifestyle of the wealthy on Fifth Avenue. Matthew Hale Smith summarized what theseflaneurs saw as the very nature of the city in his exposé Sunshine and Shadow in New York, in which he wrote, “Great cities must ever be centers of light and darkness; the repositories of piety and wickedness; the home of the best and worst of our race; holding within themselves the highest talent for good and evil.”

Dickens, Buntline, Foster, however, were all flaneurs who made their observations with an aloofness—almost a voyeurism—that established a firm distance between them and the people on the street. They were on the streets, but they were not of the streets. You might take something from their courage to go places that pushed them out of their comfort zones, but you will need to kindle your Whitman-esque attitude if you are really to become a “prince of Serendip.”

Returning to Manhattan across the Brooklyn Bridge from the ferry landing, you will need to give yourself over to the rhythms and the characters of the streets as Vivian Gornick, the modern-day Whitman, does in her essay “On the Street: Nobody Watches, Everyone Performs”:

The day is brilliant: asphalt glimmers, people knife through the crowd, buildings look cut out against a rare blue sky. The sidewalk is mobbed, the sound of the traffic deafening. I walk slowly, and people hit against me. Within a mile my pace quickens, my eyes relax, my ears clear out. Here and there, a face, a body, a gesture separates itself from the endlessly advancing crowd, attracts my reviving attention. I begin to hear the city, and feel its presence. . . . I feel myself enfolded in the embrace of the crowded street, its heedless expressiveness the only invitation I need not to feel shut out.

As you walk the streets and investigate the neighborhoods of New York City during the annual meeting, remember: “Everything changes, everything is connected, pay attention.” If you do, you indeed will make serendipitous discoveries of things you were not in search of. And if you get really good at it—like Whitman or Gornick—you might even discover things about yourself in the other people walking the streets in your midst.

is cofounder of CITY term, an interdisciplinary, experience-based semester-long program that immerses high- school students from around the country in the history, literature, and culture of New York City. He has served as its academic dean for the past 18 years and also is the coordinator of teaching and learning initiatives for The Masters School in Dobbs Ferry, New York, where CITYterm is based. He is the editor, with Kenneth T. Jackson, of Empire City: New York through the Centuries (Columbia University Press, 2002).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.