World War II and American history are not areas in which I have any claim to specialization, but at their intersection I have developed a concern. Serving as vice president of the AHA with responsibility for the Research Division has led me to think a little more about which historical documents get preserved, how they get preserved, and why. Almost everything we do as historians depends on the preservation of documents in one form or another.

My 94-year old father and two of my uncles were among the 16.5 million men and women who served in the American armed forces during World War II. Both uncles, and a third who served with the Canadian military in the War, are now dead. I have only tiny snippets of information about their lives in uniform. One flew bombing missions over Germany. Another once told me he did nothing more exciting than teach swimming in Pensacola for the U.S. Navy.

At my urging, my father recently wrote the story of his life on active duty in the U.S. Army, 1940–46. It did not take much: William H. McNeill has written more than 20 history books and still feels a day without writing is incomplete. For the great majority of veterans, it will take a bit more encouragement to get their stories preserved.

My reasons with respect to my father were personal. I wanted my children to know about his experience of war as a young man. They are now approaching the age he was then, full of bounce and life. To them, their grandfather is a slow-moving, hard-of-hearing, old guy. I feared that by the time they were patient enough to listen to his accounts of his experiences, he would not be available to relate them.

According to the Department of Veteran Affairs, about 1.7 million WWII veterans remain alive, that is, just over 10 percent of the total. Nearly 90 percent of them have already gone. About 250,000 will die this year, some 685 every day. They are now dying at a rate about three times as fast as their comrades-in-arms did between December 1941 and May 1945. Almost all will take their stories with them when they go.

Those stories are a form of national treasure. For years, historians, journalists, and family members have been collecting letters, diaries, journals, and interviews from a few of those 16.5 million. The Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress, created by act of Congress in 2000, has materials of one sort or another from 48,000 WWII vets. University libraries, state historical societies, military units and other organizations have collected a few thousand more. No one knows exactly how many, because there is no clearinghouse or coordination. But it is a safe bet that fewer than 1 in 200 WWII veterans’ stories are preserved in any fashion.

Of those veterans’ stories that are preserved, a small share has been digitized and is easily accessible to the public. The Veterans History Project has put up 7,000 World War II vets’ stories on its website. The Rutgers Oral History Archives has another 469. Other digital collections are smaller, and the total is well under 10,000. For the rest, one has to travel to a library or historical society. Adequately funded professional historians do so as a matter of course. For the public at large, and for underfunded historians, the expense is usually too great. We—the AHA and the USA—ought to be able to do better than this.

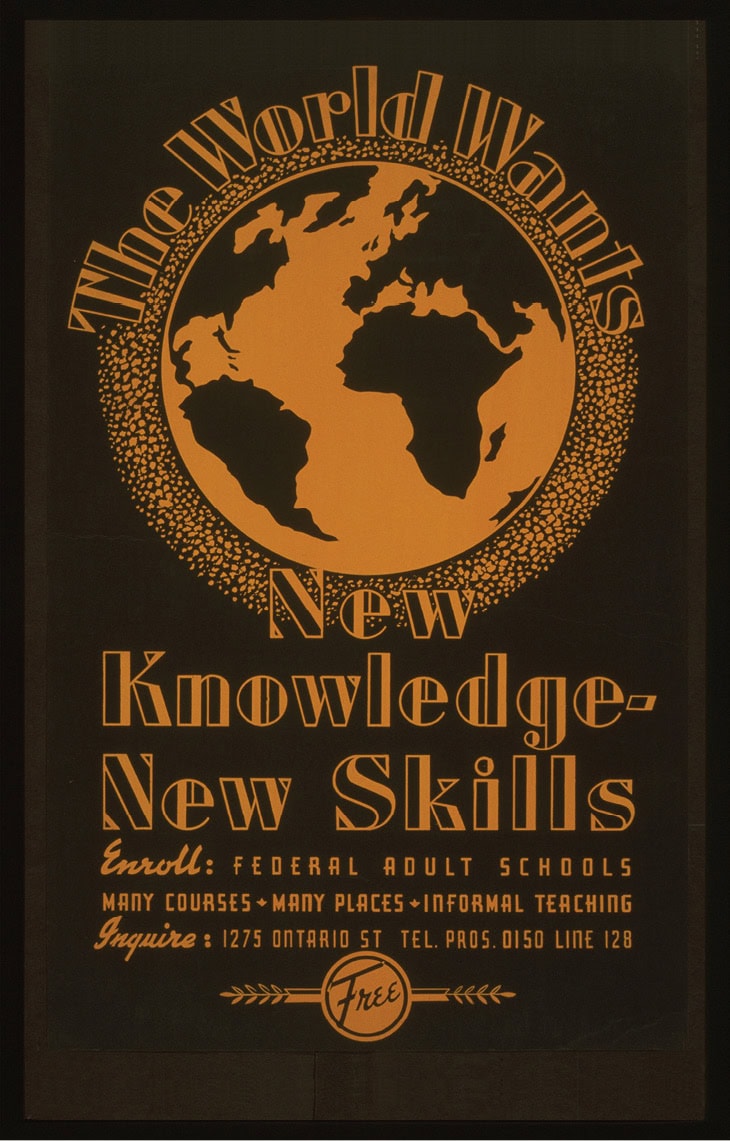

In the 1930s, the last generation of Americans who had been slaves was dying out, taking their stories with them to their graves. Few people at the time regarded the life stories of ex-slaves as an important cultural resource. But in 1937–38 the federal government, under the auspices of the Federal Writers’ Project (a New Deal program to help unemployed writers), sponsored an effort to record the stories of as many of the surviving ex-slaves as possible. About 800, most of whom were still children at the time of the Emancipation Proclamation, told their life stories, which were typed up and deposited in the Library of Congress. (A few audio recordings also exist). Altogether, the Library of Congress has about 2,300 so-called slave narratives. Most of them lay neglected until the 1960s when historians took a stronger interest in the experience of slavery. Today, all of them are available online, thanks to a grant from Citicorp. In a few seconds, if you wish, you can be reading the life history of any of the ex-slaves who got the chance to tell their story (Arkansas is the state best represented in the collection). School kids almost anywhere in the world can read these as well. Even though it only includes the stories of about 1 of every 1,500 ex-slaves who were alive at the time of emancipation, and in hindsight more should have been done sooner, the collection is another national treasure.

No ex-slaves remain alive. The last of their voices fell silent decades ago. It is too late to gather any more of their stories, but at least the federal government – just in time – supported the effort to collect those few still available. And fortunately all are now easily accessible.

In another decade, those who joined the armed forces as teenagers in the last months of 1945 will be at least 94 years old. They will be few in number, under a quarter million in all actuarial likelihood, and slow-moving like my father. They’ll be lucky if their memory is a sharp as his. Each week, 5,000 more voices fall silent.

The Veterans History Project and all the similar efforts across the country are only able to find, record, and digitize a tiny proportion of the shrinking number of stories still available from World War II veterans. Before their time runs out, we—historians, journalists, friends, family members—should help as many as possible to record their stories. And, less urgently but no less importantly, we need to get it all up on line. Who will step forward, as Citicorp did a few years ago for the ex-slave narratives, to support a sustained effort to record and digitize the stories of World War II veterans?

In the AHA membership there are at present a regrettably high number of unemployed and underemployed historians with the necessary skills to perform the task. They are, if anything, better fit for the work than were those hired by the Federal Writers’ Project in 1937–38. The stories are still there, even if fewer by the day. The historians are at hand to record those stories. But today there is no governmental body with the mandate of the Federal Writers’ Project, and as yet no philanthropic equivalent of Citicorp, willing to invest in preserving a national treasure before it’s too late.