Editor’s Note: This post is the fourth in a series of posts from the AHA Bridging Cultures project.

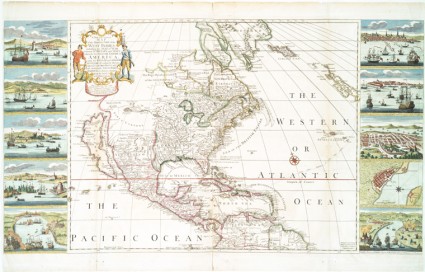

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. “A new & correct map of the trading part of the West Indies.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 28, 2016.

I was very fortunate to have had the opportunity to participate in Bridging Cultures: Atlantic and Pacific, a three-year program sponsored and organized by the AHA in partnership with the National Endowment for the Humanities. During the course of the project, 24 community college faculty from throughout the nation met at the Huntington Library in Pasadena, at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and in New York at the AHA’s annual meeting to participate in seminars and workshops with some of the nation’s top scholars to broaden our US history courses by incorporating new scholarship and approaches on the Atlantic and the Pacific worlds.

The first year, we spent a full week at the Huntington Library immersing ourselves in the latest Pacific world scholarship, as well as conducting our own research at the library’s vast collections on California, the American West, and the Pacific world. Our presenters challenged us to consider the vast Pacific Ocean as a unit of analysis; to reframe “national histories”; to consider global connections more fully, including between commodities, crops, germs, and technologies; and in general, to encourage our students to “think Pacifically.”

The second year we spent a wonderful (if “Polar Vortex” chilly) week at the Library of Congress. Our speakers challenged us to “think Atlantically” and to expand the boundaries of our US history courses by considering John Elliott’s definition of Atlantic history—“the creation, destruction, and re-creation of communities as a result of the movement, across and around the Atlantic basin, of people, commodities, cultural practices, and values.” We spent the year incorporating these new Atlantic and Pacific approaches in our survey courses, as well as “defamiliarizing” and “unsettling” seemingly familiar narratives.

The third year we met at the AHA’s annual meeting in New York. I chose to focus my presentation on “Chocolate, Sugar, Coffee, and Guano: Commodities and Coerced Labor in the Americas across the Atlantic and the Pacific” for several reasons. Examining commodities and their broad social impact allows us the opportunity to cast our nets wide to get students to think about US history in a broader context, as well as to examine the ways that the demand for these commodities pulled the Atlantic and Pacific worlds together to shape the Americas over the course of five centuries.

My students have found it fascinating to learn from the work of Marcy Norton, John McNeill, John Thornton, and others that exposure to bitter stimulant beverages like Mesoamerican chocolate throughout Europe (as well as coffee) led to an increased demand for sugar, and that the increased production of all three commodities in turn fueled the number of enslaved Africans directed to the Caribbean, Brazil, Mexico, and other parts of the Americas from the 16th century through the end of the 19th century.

These approaches give students the opportunity to examine tastes and cultural practices as a vital part of the Columbian exchange, and to learn about the Caribbean and its deep connections to the United States much more closely. My students are surprised to learn that the Caribbean had a Taino population of almost 5 million people and that waves of diseases like smallpox and yellow fever decimated this sizeable indigenous population, as they did the majority of the 60 million indigenous inhabitants of the rest of the Americas. Further, it was demand for commodities like sugar, coffee, and tobacco that led planters and slave traders to direct almost 5 million enslaved Africans to those very islands (almost 12 million to all of the Americas). And when slavery was finally abolished in the Caribbean (not until 1886 in Cuba), the demand for those same commodities led to yet another form of coerced labor in the Americas—the importation of tens of thousands of Chinese indentured servants throughout the Americas. Incorporating film clips like Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s Black in Latin America series, as well as primary sources by Olaudah Equiano, Mary Prince, Esteban Montejo, and Toussaint Louverture, to name a few examples, also helps give our students a sense of the broader Atlantic and Pacific connections as well as “defamiliarize” conventional narratives.

I’ve included a few examples here of some classroom assignments and activities that challenge our students to think “Atlantically” as well as “Pacifically” as they think broadly about American history. The first four consist of readings, primary sources, and film clips on the complexities of the Transatlantic slave trade and the broader Atlantic world during the colonial era. They ask students to grapple with narratives of the enslaved, letters from merchants, accounting ledgers, and scholarly articles on the centrality of colonial labor systems as well as the survival of African religions across the Americas. The other two focus on the expansion of the United States as it becomes an imperial power and has students critically examine the US–Caribbean relationship, Hawaii, and the Philippines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the Bridging Cultures Resources:

- Discussion Questions on US Imperialism

- Discussion Questions on Manifest Destiny

- Discussion Questions on Revolutions, Independence, New Nations

- Discussion Questions on the Film Black in Latin America

- Discussion Questions on Black Atlantic World

- Discussion Questions on Africans in the Americas

Check out of the complete resources.

Carlos Alberto Contreras has a PhD in history from UCLA and is a professor of history at Grossmont College in San Diego, where he teaches the comparative history of the Americas, modern US history, and the history of Mexico.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.