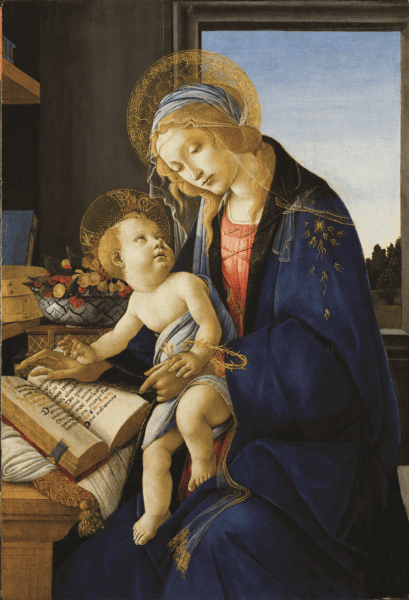

Throughout Christian history, the Virgin Mary has been depicted as a young mother nurturing her child, and as an older mother mourning her son. Both depictions of Mary have been made to revere her in different parts of the world, but some images of the young mother are more unusual than others. These depictions—usual and unusual—were the subject of the two-day symposium “Picturing Mary,” co-organized by the Catholic University of America and the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Speakers at the symposium covered topics such as “The Qur’anic Virgin Mother,” “Goddess Guadalupe: How Mexico’s Mother Image Became a Cultural Icon,” and “The Pietà at the 1964/1965 New York World’s Fair.”

For example, in a 15th-century engraving the Virgin Mary gives the gift of her breast milk to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, whose eye is healed after it is touched by the milk.

In her keynote address Miri Rubin, celebrated scholar of the medieval period and author of Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary, cited the 14th-century Werner the Swiss’s poem describing Mary’s breasts:

Two noble dates, little apples

sweet and fair:

God saw them

and came thither

in search of sustenance,

took them at once

in His mouth

with joy:

thus his love was set on fire.

I mean, if I may praise it,

your noble breast, full of grace,

beautiful,

so praiseworthy

that God himself valued

it above all that was ever His,

lauds it with worthiness,

wished to thrive and grow at it:

for it was His desire

to kiss it,

he nestled against it,

suckled it with joy

and entered your womb:

Wherefore your praise will always be great![i]

In her book on Mary, Rubin writes that in the 13th century, Mary’s “body is often explored with particular attention to her breasts, which became more visible in art and more explicitly considered in poetry.” In fact, in that century Mary was imagined as baring her breast as she intercedes for mankind in the Last Judgment—her breast becomes the symbol for her care. In chapter 12 of her book, Rubin devotes a section to the subject called “Mary’s Breasts and Family Nurture.”

But early texts, too, refer to Mary’s body. In the earliest Syriac Christian text, Odes of Solomon, we encounter these verses:

The son is the cup

And the father is He who was milked;

And the Holy Spirit is she who milked him…

The womb of the Virgin took it

And she received conception and gave birth.

So the Virgin became a mother with great mercies.

And she laboured and bore the Son, but without pain,

Because it did not occur without purpose.

And she did not require a midwife,

Because He caused her to give life.[ii]

Not only in visual art but also in writing and performance, people imagined different aspects of Mary’s life, and medieval Christians were not shy in their adoration of all of Mary, as a woman, wife, and a human with a body. In medieval England, dramatic representations of Mary and Joseph’s relationship show them as a couple who fights like other couples do. When Joseph finds out about Mary’s pregnancy, he does not accept the news at first, and his mutterings in that period of doubt have him speaking of his betrothed as an angry man might speak of any human woman. Vanessa Corcoran, a doctoral candidate at Catholic University who presented at the conference, is writing her dissertation on the Corpus Christi plays and Mary’s voice in them. “The Corpus Christi plays were liturgical performances in the vernacular (in this case, Middle English) from the late 14th century through the mid-16th century in urban settings throughout England,” Corcoran wrote in an e-mail. “Through a series of guild-sponsored pageants, these plays told the story of salvation from Creation to Doom, intertwining biblical stories with medieval motifs.” But these plays are so colorful that Corcoran prefaced her talk with a warning; the English playwrights were sometimes harsh in their imaginings of Joseph’s mutterings.

Artistic depictions of Mary will be on display at the exhibit Picturing Mary at the National Museum of Women in the Arts until April 12. Catholic University will also stage The Annunciation, a contemporary version of a medieval play, on April 14 and 15.

Notes

[i] Translated by Timothy R. Jackson in “Erotic Imagery in Medieval Spiritual Poetry and the Hermeneutics of Metaphor,” in Metaphor and Rational Discourse, eds. Max Bernhard Debatin, Timothy R. Jackson and Daniel Steuer (Tuebingen, 1997).

[ii] This quote is taken from Rubin’s book; the verses are edited and translated by James Hamilton Charlesworth (Oxford, 1973).

The author’s name has been withheld.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.