There are few American cities in which jarring juxtapositions—of old and new, luxury and squalor, forthrightness and fantasy—assert themselves as aggressively as they do in New York. Such contrasts seemed particularly evident in the weeks leading up to this year’s annual meeting. Protests against police violence unfolded against a backdrop of twinkling lights and holiday shopping as Christmas carols mingled with sorrowful chants and harrowing accusations. On the last Saturday of 2014, I took visiting family to Ellis Island, a destination known to blend heartache with hope. As our ferry made its way down the Hudson River and rounded the Statue of Liberty, the gaze of everyone on board wandered from her soaring torch to a row of helicopters flying in solemn formation above it for the funeral procession of Rafael Ramos, a police officer shot and killed in Brooklyn just five days shy of Christmas.

Whether a consequence of the host city’s spirit or a reflection of the discipline’s own mood, the annual meeting that began a week later saw a critical mass of panelists eager to engage problems more imperative than abstract, their assorted subjects’ contradictions exposed anew rather than explained away. From Jan Goldstein’s stirring presidential address to sessions on the evolving crisis in Ukraine and the now-endangered Voting Rights Act, William Faulkner’s warning was borne out by one panel after another: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Faulkner’s adage found its fullest expression from a panel on the meeting’s final day. For those of us who usually study a past long passed, attending a session whose subject is as raw and ongoing as “Understanding Ferguson: Race, Power, Protest, and the Past” can elicit considerable admiration and nagging uncertainty. Admiration because the energy in the room is high, the panelists electrifying, and the belief in history’s importance voiced powerfully and often. Uncertainty because if heard too many times, “history matters” has the ring of a truism. That history itself matters, no one who convened at the midtown Hilton had any doubt. That historians matter—or rather, how they have and should—is another problem entirely.

What made the Ferguson session particularly well suited to unraveling that problem was not only the pressing importance of the topic, but also the variety of angles from which panelists approached it. Is it prosaic to talk about tools? There’s nothing prosaic about the tools themselves when handled by historian Colin Gordon; his maps and tables illustrated trends whose origins and impact can be hard to convey in words alone, uncovering chapters in the story of greater St. Louis lost in most reports on Ferguson last fall. Decade by decade, Gordon showed us neighborhoods segregated by race and wealth as “private and public strategies of exclusion overlapped and reinforced one another.” As black flight followed white, inner-city poverty moved from the city’s near north side to its inner suburbs. “We’ve made some gains on wages and income,” Gordon concluded, “but the wealth gap is growing, and that is all about housing.”

Distinguishing Gordon’s presentation was a deft use of difficult tools and a clarity of emphasis (housing) amid reams of data. Uniting panelists Khalil Muhammad and Heather Thompson was a shared subject (policing, criminalization) and philosophy (that historians, in Thompson’s words, “have an obligation to weigh in on these discussions”). Muhammad summoned E. Franklin Frazier’s legacy to show how easy it is for evidence to go unheeded when historians fail to take a seat at the policy table. Appointed by Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to investigate causes of the 1935 Harlem riots, Frazier and his committee cited “injustices of discrimination in employment, the aggressions of the police, and the racial segregation” of the neighborhood. Sound familiar? The report, Muhammad says, “gathered dust on a shelf in city hall,” only to see its insights “rediscovered” in every comparable commission that followed. From the 1968 Kerner Commission in Chicago to the Christopher Commission’s report on policing in Los Angeles in 1991, identical themes emerged without “sticking,” by Muhammad’s reading, each theme fading from public view as the crises they helped cause subsided. In the space left where a sustained public discussion belonged, “a myth of post racialism” (Thompson’s phrase) took root instead. But the events in Ferguson last year—not only the death of Michael Brown, but the failure to bring the officer responsible to justice; the outpouring of grief and frustration that followed; and the ferocious state response to community protests—induced a sickening sense of déjà vu in observers nationwide. Thompson regards that sense as not just feeling but fact: “we have indeed been here before,” and the narrative that historians are left countering “is that there’s something weird about this, something exceptional.”

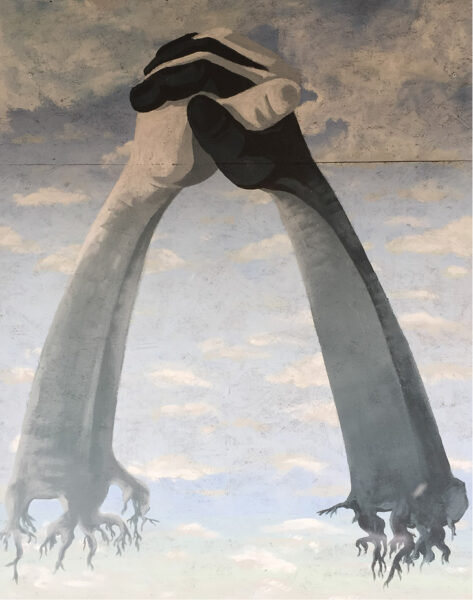

This painting was made on the boarded-up window of a business on South Grand Boulevard in St. Louis, Missouri, after the grand jury decision not to indict Darren Wilson in the killing of Michael Brown. The photograph of the painting was taken by Kevin Dern.

Thompson thanked her fellow panelists for providing “deep historical context,” and by my count, context was a word used 29 times in two hours. It is a term common to historians, invoked frequently in conversations about what we do—historians provide context. Panelist Jelani Cobb added dimension to the term by asking that we not merely regard it as something historians provide for the participants in an event, but remember as well “that people enter something with context of their own.” Listen to Ferguson residents, says Cobb, and you’ll hear a timeline that extends back well before the afternoon last summer when Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown. The people Cobb spoke with “were much less likely to talk about what happened between those two individuals” on Canfield Drive than to take issue with a decade of school closures, the destruction of a housing project, or the practice of raising municipal revenue through traffic fines and parking enforcement. Others extended that timeline back further still to explain (this to a professional historian) “the importance of the Dred Scott decision in Missouri, and how that connected to what happened in Ferguson.” Cobb also spoke directly to the discomfort felt by historians more at home in an archive than at a protest, and those who worry that to study history is a pursuit best kept separate from participating in or reporting on it. Describing himself “as someone who has one foot in the past and also who is chronicling things in the present,” Cobb feels “able to understand the past better via the work I’m doing in the present and then understand the present better, as historians must, via the work we do in the past.” Cobb’s enviable ability to plumb the past such that its stakes for the present become abundantly clear makes his dispatches from Ferguson (published in the New Yorker last fall) a model of the work Thompson and Muhammad would like to see more of.

The session’s final panelist, Marcia Chatelain, embodies that ideal as well, as a teacher—a vocation she interprets with its broadest possible mandate. If there were ever a historian who put her money where her mouth is, it’s Chatelain. During the panel she encouraged the cultivation of unlikely allies. Look to see what she’s done before and since and you’ll find just that: Chatelain communicates with a remarkable range of people eager to learn—with grade-school teachers from Utah, with Girl Scouts and incarcerated children, and with a universe of faculty looking for ways to talk and books to assign via #FergusonSyllabus. So what if one’s role as historian, teacher, reporter, and participant can sometimes seem “awkward”? Chatelain is the patron saint of the awkward, the kind of gifted teacher who can discuss dire circumstances with such generosity of spirit that painful questions give way, if not to solutions, then at least to a wedge in the door. Teaching Ferguson is “really a civics lesson” in which Chatelain has found failures, to be sure, but also “a lot to celebrate,” including “a critical mass of scholars of color.” Chatelain would have historians of all stripes “model” conversations about injustice for those unaccustomed to having them. “Students need to be able to fumble through this,” Chatelain insists, learning not only the facts but that “this is what people do in the world. Engaged people talk about things.”

To say that “history matters” is not then to say that historians do. But if next year’s annual meeting includes a panel on a comparable topic and the conversation has moved haltingly forward, we might say—with admiration to spare and nagging uncertainties answered—that both are true. And if New York City’s magnificent contradictions and conspicuous inequities helped set the tone for this year’s meeting, what might Atlanta lend next year’s? After all, even annual meetings have a context, and a city that rose from the ashes of the Civil War to become the transportation and cultural hub of a region will surely lend its own distinct character to conversations held within its borders. I look forward to hearing them.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.