For the past 10 years digital archives and crowdsourcing have been popular forms of digital history, as scholars have harnessed the power of both massive servers and a willing public to digitize and transcribe diverse types of historical material ranging from menus to weather reports. Few have excited me as much as Colored Conventions. A work of impressive scholarship, important activism, and valuable pedagogy, the Colored Conventions Project (CCP) hits for the cycle. The primary goal of the CCP is to recover an understudied aspect of the 19th-century reform movement, black conventions. Between 1830 and 1900 African American men and women from all walks of life organized over 150 state and national conventions that advocated for their legal, educational, labor, and voting rights.

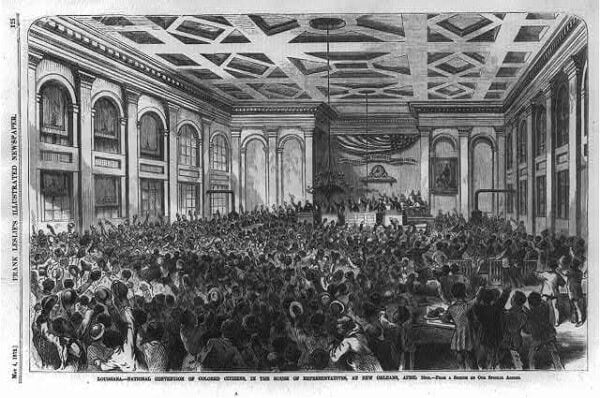

“1872 National Convention of Colored Citizens Held in New Orleans, Louisiana,” ColoredConventions.org

The Colored Conventions Project seeks to better understand not only those male delegates explicitly mentioned in the minutes of the conventions, but also the women who made this century-long rights struggle possible. It does this through an unprecedented effort to digitize, transcribe, and interpret newspapers, petitions, conference proceedings, and any other records that documented these conventions. By democratizing the process of recording, interpreting, and disseminating historical knowledge on this understudied portion of American history, the Colored Convention Project aims to make scholars, students, and the public a part of the effort to better understand and remember the past.

Initiated by the faculty, staff, and students at the University of Delaware, the CCP represents a growing push by scholars to self-consciously engage the public and involve it in the creation of their work. The CPP, for instance, has uncovered new material on Colored Conventions by actively involving church congregations whose denominations hosted conventions in the 19th century, as well as general members of the public. More than 1,300 undergraduate and graduate students at universities across the United States have used the growing database of transcribed minutes, articles, and proceedings to generate an impressive set of exhibits using CCP sources to examine the 19th-century black rights movement. The Colored Conventions website hosts three videos highlighting the project’s work and offering an introduction.

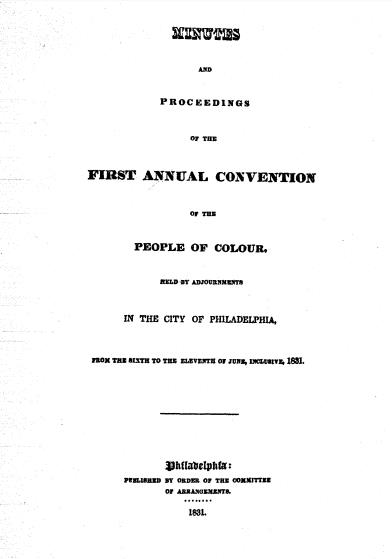

The first page of the minutes of the 1831 Convention in Philadelphia available as a pdf and in plain text on the Colored Conventions Project.

The CCP does much more than ably document past activism. In its teaching section the CCP offers a range of lessons, projects, and assignments for undergraduate and graduate classes that actively involve students in the valuable work of better understanding and presenting the past. The most notable set of lesson plans is “Colored Conventions in a Box.” This curriculum provides students the opportunity to create their own online exhibits with Omeka, a web publishing platform geared towards schools, libraries, and museums.

It is in these exhibits, some of which are available on the website, where the CCP shines brightest. Offering a fascinating glimpse into the routines of day to day life, they demonstrate the ways that ordinary things such as food and boarding, which one exhibit refers to as the “‘conventions’ of conventions,” shaped the act of politics. This fits with the project’s second goal of making the political work of African American women in these conventions more visible. Largely hidden from the public record, the CCP pushes students and users to look underneath the surface to uncover the ways that women shaped public behavior.

While I would like to implement the “Colored Conventions in a Box” curriculum in my classroom, unfortunately my school has neither the time nor resources for a project of this magnitude during the regular school year. Instead, I integrate the CCP into my AP US history class by using it directly in the classroom through lecture, readings, and discussion. Portions of the CCP corpus of transcribed proceedings and minutes can be easily accessed by students and instructors through the “Conventions” tab or via the downloadable zip file. My students were particularly interested in the pdfs of the digitized minutes and newspaper articles, as well as maps and tables that present the geographic scope and substantial numerical differences between the conventions.

In my US history courses I combine the digitized files, maps, tables, and exhibits from the CCP to foster a better understanding of 19th-century reform movements and to teach important historical thinking skills. I also push students to explore the ways that these resources demonstrate how both history and activism are made up of much more than the important figures and places that all too often dominate our shared understanding of the past.

I begin my use of the CCP with a brief explanation of the role of Colored Conventions in the reform movements of the 19th century, emphasizing how reform movements fed off and reinforced each other. In particular, I use the word trends tool of the CCP to discuss with students the role of temperance in early conventions and the ways that Colored Conventions later interacted with women’s suffrage.

This leads to further discussion on the ways that reform movements evolved. I supplement this conversation by giving students portions of minutes from conventions in 1830, 1855, and 1872, asking them to compare the topics covered in the three meetings. What changed? What stayed the same? What events surrounding these conventions shaped the topics of discussion? This activity leads students to directly engage in the AP identified historical thinking skills of continuity and change, and contextualization.

Next, I ask students to do a quick write-up on what it means to be an activist. How does one effect political change outside of the realm of formal politics? After sharing some of their answers we look at portions of the exhibits “African American Women’s Economic Power,”“The ‘Conventions’ of the Conventions,” and “What Did They Eat? Where Did They Stay” to explore the ways that history and activism can be found in the seemingly mundane, obscure, and “unimportant” parts of the human experience. While middle school students might find text analysis tools and the language of convention minutes difficult, these exhibits are engaging examples of ways to engage in politics that can be applied to their own lives. At the very least, the exhibits of the CCP stress agency, action, and humanity, and offer important counters to the ways that the lives of African American men and women are too often portrayed in discussions of the 19th century. The CCP’s multiple goals connect it to a wide range of digital projects examining Black life during the 19th century. Its first goal, the examination of black rights struggles during the 19th century, can be further encountered in the Texas Runaway Slave Project, the University of Richmond’s impressive Visualizing Emancipation, and the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative’s After Slavery, to name a few. The CCP’s attention to the seemingly mundane, best exemplified in its exhibits, can be further examined through the Black Press Research Collective and the Library of Congress’ collection of African American newspapers. Black Quotidian, discussed in a recent Perspectives article, continues this theme into the 1900s, by highlighting various articles from the black press that often directly respond to current themes.

In concert with the projects mentioned above, or by itself, use of CCP in the classroom encourages students to get involved in the study and production of an important part of the American past that is too often ignored. It pushes them to consider the roles of little-known actors and to explore ways to recover their voices. Finally, by exploring the nature of activism in the 19th century, students can discuss how they can get involved in the 21st.

I have included an assignment below that utilize the resources made available by the CCP. While I have yet to use it in my classroom, I look forward to implementing it in the coming years. Have you used Colored Conventions in your classroom? Do you have any suggestions on how it could be used? Let us know in the comments or via twitter (@johnrosinbum; @CCP_org would also love to hear from you!). Next month we’ll welcome a guest post from Kalani Craig, clinical assistant professor at Indiana University Bloomington on the use of digital history when teaching the Black Death.

Sample Assignment: Annotation, Contextualization, and the Colored Conventions Project

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.