Editor’s Note: This article discusses sexual assault and violence.

I went to the 2020 AHA annual meeting looking for true crime stories. What I found was an important, emerging set of questions about the nature of privacy and the affordances of new forensic histories that pushed me to reflect on the roots of my own scholarly enterprise.

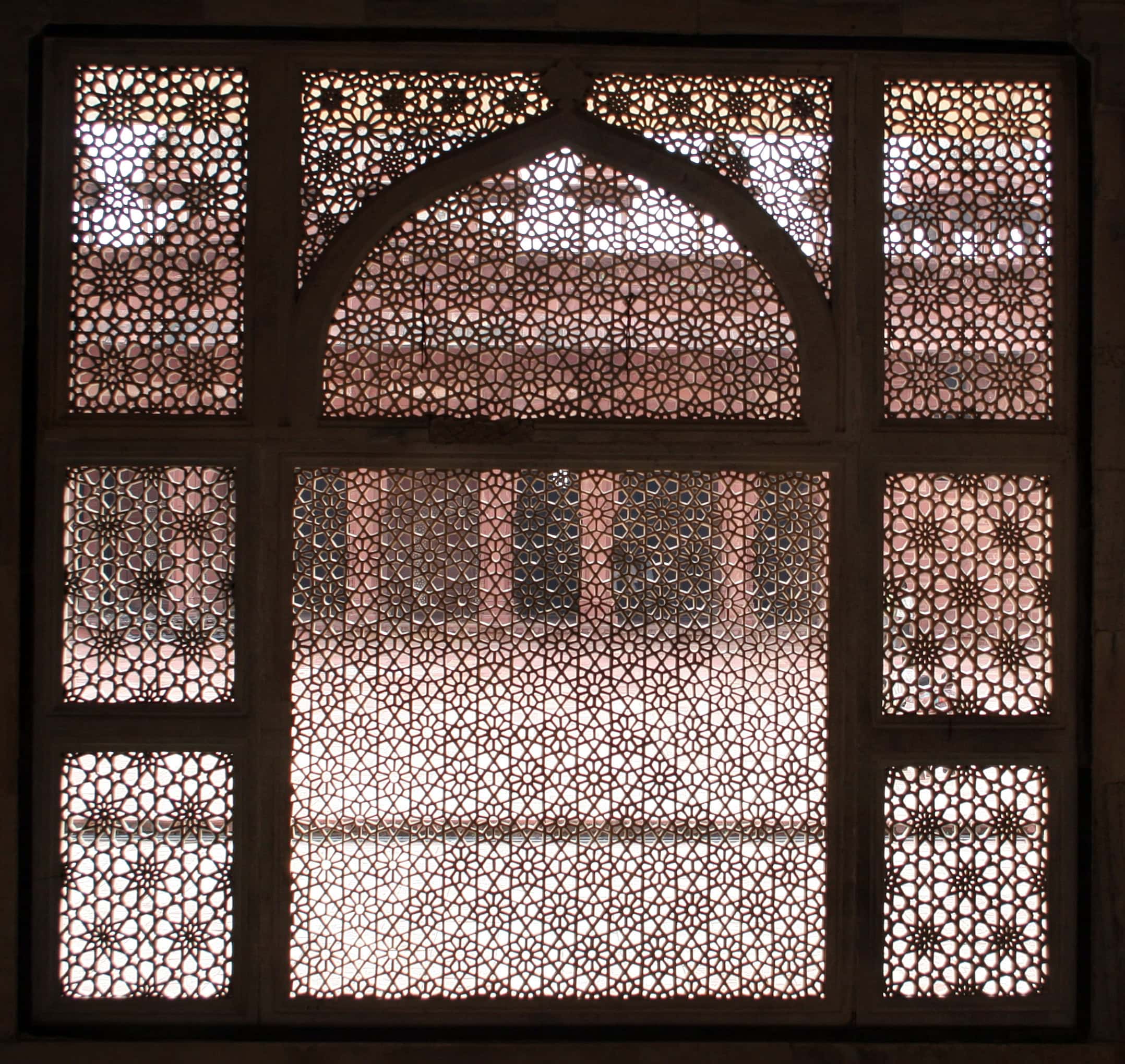

At AHA20, observed that the people at the heart of histories of violence remain hard to conjure. Their stories end with the sense that there is something there that cannot be accessed through traditional historical methods. Timon Studler/Unsplash

I’m a historian of murder—I write in particular about women who killed men in the 19th century; shout-out to Lizzie Borden—but true crime is, unfortunately for me, not a very popular mode of historical analysis. I’m also a medical historian, but I’m less interested in viruses and pathogens than I am in how human action produces pain and injury within bodies. I am especially fascinated by the role that violence, both interpersonal and state-sanctioned, plays in the history of women’s health. Heading to AHA20 with my eye out for medical histories with the flavor of true crime, I found instead a rich network of scholars asking questions about violence, gender, privacy, the state, and the construction, uses, and abuses of knowledge about women’s bodies.

Seeking out murder-adjacent medical histories led me in directions I hadn’t anticipated. Alicia Gutierrez-Romine (La Sierra Univ.), in a panel titled Public Health Innovation in Times of Crisis, presented on “Tijuana abortions,” tracing the practices of women evading US criminal law by seeking abortions south of the border and the role these operations played in the decriminalization of abortion in California in the late 1960s. In another panel, Disability, Gender, and the Great Depression in the United States, Susan Schweik (Univ. of California, Berkeley) discussed the complicated position of institutionalized women in experiments at the Glenwood State Institution for Feeble-Minded Children in Iowa. Bianca Premo (Florida International Univ.) captured the interplay of these questions in her paper on the case of Lina Medina, who is claimed as the youngest documented mother ever to give birth, during the session Proof: Technology, Knowledge, and the Body in Early 20th-Century Latin America. In concert, these papers helped me think in new ways about writing the history of murder by focusing on the nature of privacy.

In her work on so-called Tijuana abortions, Gutierrez-Romine traces the 1969 decriminalization of abortion in California to the practice of American women crossing the US–Mexico border to obtain cheaper abortions outside of US jurisdiction. During the mid-20th-century period of criminalization, hospitals on the US side of the border began observing “Monday morning line-ups”: women who received their paychecks on Friday, crossed the border on Saturday for operations, often at the hands of untrained surgeons, and returned at the close of the weekend with serious medical complications. As those emergency room lines grew longer, lawmakers’ discourse surrounding abortion turned to questions of legal liability for physicians in the United States who performed abortion procedures to protect their patients against the dangers of medical tourism. The landmark People v. Belous decision in the California Supreme Court addressed these concerns by decriminalizing abortion in 1969—a path to legalization, as Gutierrez-Romine observed, started by the anonymous women whose presence in emergency rooms and on operating tables necessitated the change in the law.

AHA20 helped me think in new ways about writing the history of murder by focusing on the nature of privacy.

Schweik presents a similar narrative in the case of the women of Iowa’s Glenwood State Institution for the “feeble-minded” who became participants—not subjects—in a study of intelligence that destabilized eugenicist concepts of intelligence. In the 1939 Skeels-Dye experiment, women incarcerated in Glenwood, many of whom had been committed involuntarily in a eugenicist effort to control their reproduction through hospitalization and sterilization, cared for children two to three years of age who had been removed from a nearby orphanage after scoring low on IQ tests. The children, subjected to the same tests after years of care from the women of Glenwood and again throughout adulthood, not only scored higher in IQ points but evidenced what the study’s authors considered markers of success: high rates of both employment and marriage coupled with low rates of institutionalization and criminal activity. Through these results, the women of Glenwood dealt a heavy blow to eugenicist notions of intelligence as “fixed”—but, as Schweik noted, researchers both at the time and since ignored the role and experience of the women at the heart of the study. Like many of the true crime stories I study, this narrative features violence (in this case, the violence of eugenicist thought) followed by silence: all we really know about these women is that an overwhelming majority were white, many had been separated involuntarily from their own children, and all were poor.

Premo, in contrast, studies a female subject to whom she can put a name and a face. Her name is Lina Medina, and in 1939, she gave birth at age five by caesarian section, making her the youngest documented mother to ever give birth. Yet despite the specifics we know about the case, Premo presented to her audience the difficulty of telling a clear narrative in the face of continuing arguments that Medina’s case was a hoax. The story appeared in both medical journals and popular press accounts in Peru and the United States. Some attempted to describe Medina’s pregnancy at age five as normal; others portrayed her as a medical miracle (or, less generously, a “freak,” as she was described by the press at the time). But Peruvian papers never printed photographic evidence of Medina’s condition, and only a single photograph exists of the young mother during her pregnancy. Premo showed this photograph, but with significant censoring: it is a nude photograph of a five-year-old girl whose pregnancy, if true, could only be the result of sexual violence, most likely perpetrated by her father. It is this specter of violence, as much as a lack of documentary evidence, that makes it difficult to discern the facts in the case. Medina is still alive but has resisted the attempts of journalists and researchers to get her to speak on the case, and ethical considerations prevent us from breaching the wall of silence she has built.

In each of these histories, the people at the heart of the story remain hard to conjure. They are victims of violence at the hands of doctors, institutions, and family members. They are women, they are disabled, they are colonial subjects, they are brown, they are poor: all of which means varying layered degrees of invisibility. At the same time, they are the primary actors driving the narrative of change. Each of these stories ends with a sense of promising ambiguity—the sense that there is something there, we just can’t access it through traditional historical methods.

Is there a feminist forensic history that could refocus our work toward forms of knowledge more closely tied to bodily experience?

This archive problem is, of course, not a new discovery: it’s become commonplace to acknowledge the “silences” or “absences” of women’s history, to talk about “voice,” “agency,” and the lack thereof. That silence often gets redoubled in histories that feature crime or violence, where practical and ethical concerns mingle for both historical actors and historical researchers.

Maybe the solution to this dilemma lies in the methods proposed by tech-driven, STEM-oriented historical research techniques employed by scholars of the Anthropocene. “Forensic history,” as these methods were called in a panel chaired by Kate Brown (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), offers historians the opportunity to understand early modern peasants through their dental remains or enslaved Africans in the US South through traces of DNA on their pipes. Is there a feminist forensic history that could refocus our work away from textual sources and toward other forms of knowledge more closely tied to bodily experience?

And if these methods can indeed put us closer to historical truth about victims of violence, those insights may prove materially useful in the present. I was excited to hear, during the Female Killers in the 20th Century session, that Carolyn Ramsey (Univ. of Colorado Law School) is working on a book about domestic violence in the pre-1970s United States. I hope that the further scholars like Ramsey can trace the origins of the specific entanglement of cultural ideology and legal inadequacies that lead to intimate partner violence, the greater our ability will be to unravel the vast social web that has trapped women in the cycle of abuse since long before Lenore Walker coined the term in the 1970s. History alone can’t solve our problems, but it often gives us insights on how to start.

Yet my journey at AHA20 holds another lesson, I think. Like all people who seek out true crime stories, I’m constantly interrogating my own motives. As a historian, I spend my time looking for stories of dramatic, violent personal tragedy, but that’s not what I found at AHA20. Bouncing between sessions on histories I thought of as more or less distant from my own interests, I considered the broader forms of tragedy and violence that drew me to those seemingly unrelated panels. I began reflecting on questions of privacy and methodology I hadn’t even realized I was trying to answer. I didn’t find what I was looking for at the AHA annual meeting—and I think I am all the better for it.

R.E. Fulton is a historian of medicine, gender, and crime holding a master’s in American history from the University of Rochester. They tweet @rebfulton.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.